预约演示

更新于:2025-05-07

MRSA vaccine (VLP Biotech)

更新于:2025-05-07

概要

基本信息

在研机构- |

非在研机构 |

权益机构- |

最高研发阶段无进展临床前 |

首次获批日期- |

最高研发阶段(中国)- |

特殊审评- |

关联

100 项与 MRSA vaccine (VLP Biotech) 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

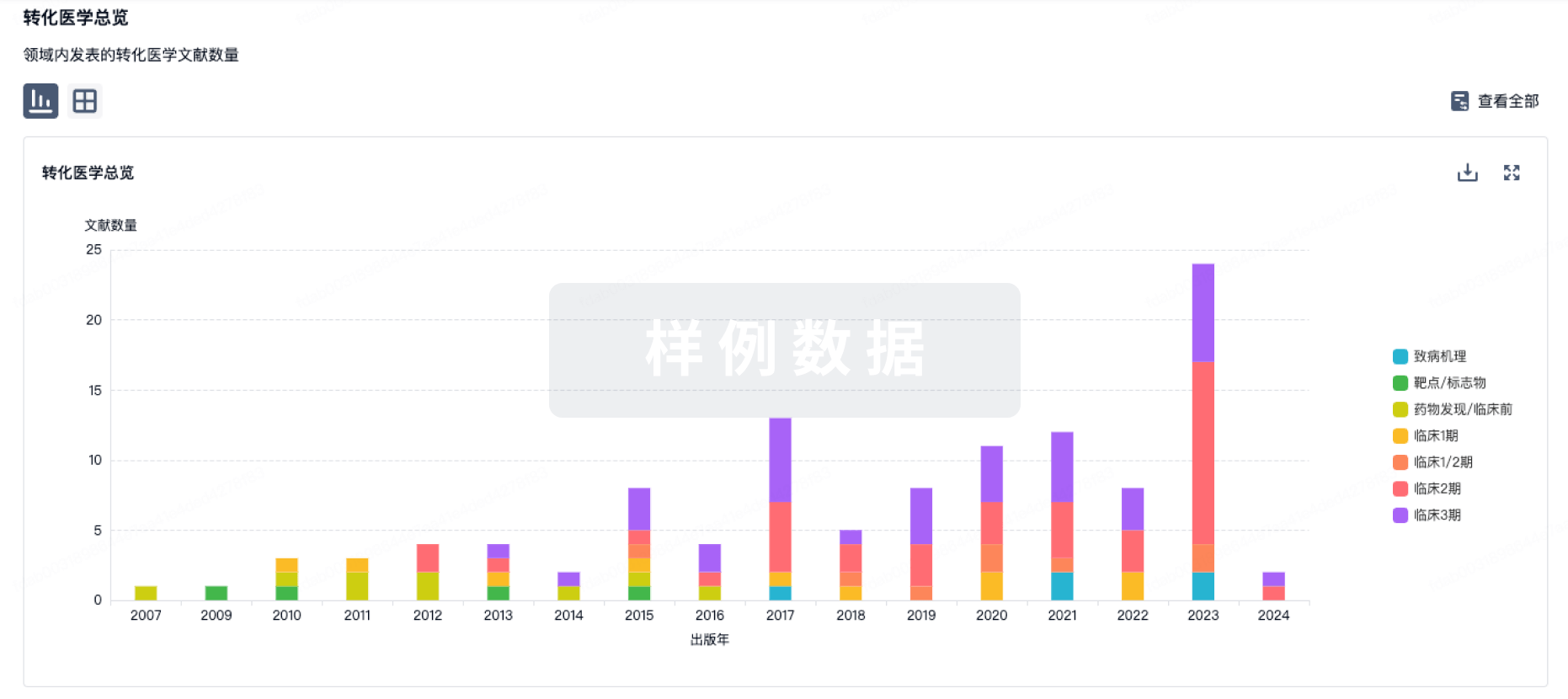

100 项与 MRSA vaccine (VLP Biotech) 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

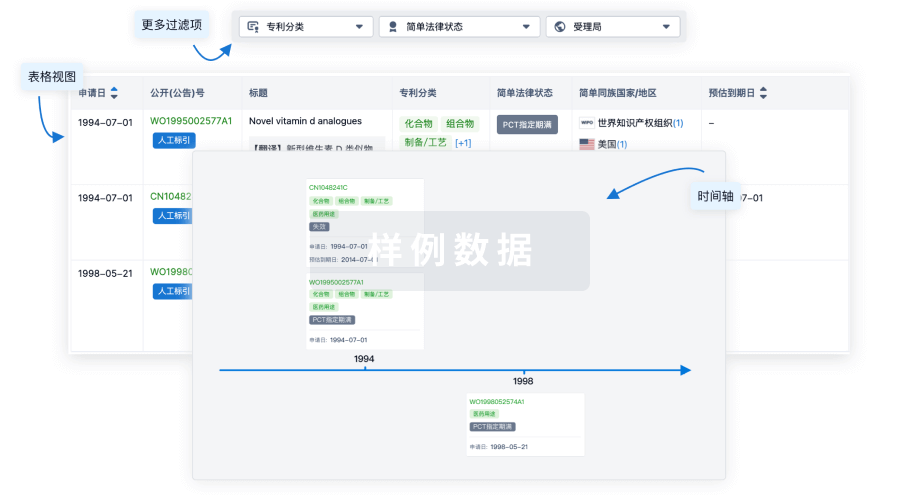

100 项与 MRSA vaccine (VLP Biotech) 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

5

项与 MRSA vaccine (VLP Biotech) 相关的文献(医药)2018-09-01·Acta Biomaterialia1区 · 工程技术

An immunopotentiator, ophiopogonin D, encapsulated in a nanoemulsion as a robust adjuvant to improve vaccine efficacy

1区 · 工程技术

Article

作者: Yang, Yun ; Tong, Ya-Nan ; Mao, Xu-Hu ; Peng, Liu-Sheng ; Yang, Liu-Yang ; Sun, Hong-Wu ; Song, Zhen ; Zeng, Hao ; Gao, Ji-Ning ; Zou, Quan-Ming

2010-05-01·AORN Journal4区 · 医学

Methicillin‐ResistantStaphylococcus aureus: An Update

4区 · 医学

Review

作者: Hoque, Happy ; Durai, Rajaraman ; Ng, Philip C H

2007-02-01·Future Microbiology

Prospects for a MRSA Vaccine

作者: Lindsay, Jodi A

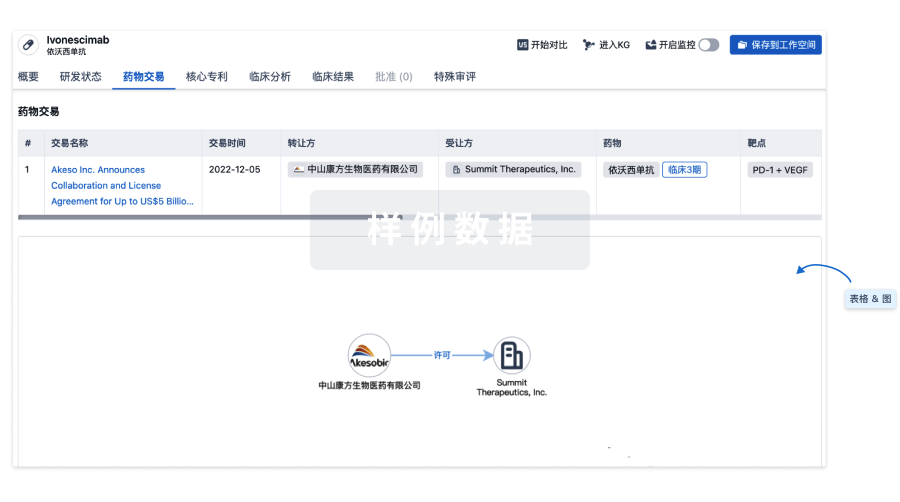

100 项与 MRSA vaccine (VLP Biotech) 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

研发状态

10 条进展最快的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 最高研发状态 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 金黄色葡萄球菌感染 | 临床前 | 美国 | 2016-01-01 |

登录后查看更多信息

临床结果

临床结果

适应症

分期

评价

查看全部结果

| 研究 | 分期 | 人群特征 | 评价人数 | 分组 | 结果 | 评价 | 发布日期 |

|---|

No Data | |||||||

登录后查看更多信息

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

核心专利

使用我们的核心专利数据促进您的研究。

登录

或

临床分析

紧跟全球注册中心的最新临床试验。

登录

或

批准

利用最新的监管批准信息加速您的研究。

登录

或

特殊审评

只需点击几下即可了解关键药物信息。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用