预约演示

更新于:2025-05-07

Dandy-Walker Syndrome

丹迪-沃克综合征

更新于:2025-05-07

基本信息

别名 Atresia of foramina of Magendie and Luschka、Cyst, Dandy-Walker、Cysts, Dandy-Walker + [67] |

简介 A congenital abnormality of the central nervous system marked by failure of the midline structures of the cerebellum to develop, dilation of the fourth ventricle, and upward displacement of the transverse sinuses, tentorium, and torcula. Clinical features include occipital bossing, progressive head enlargement, bulging of anterior fontanelle, papilledema, ataxia, gait disturbances, nystagmus, and intellectual compromise. (From Menkes, Textbook of Child Neurology, 5th ed, pp294-5) |

关联

5

项与 丹迪-沃克综合征 相关的临床试验DRKS00036116

MULTICENTER / OPEN-LABEL / NON-INTERVENTIONAL PMCF STUDY OF THE PERFORMANCE AND SAFETY OF XABO® Catheters IN PATIENTS SUFFERING FROM THE FOLLOWING CONDITION: Hydrocephalus of any aetiology - PMCF-Study XABO®

开始日期2023-10-16 |

NCT03078868

Utility of Diffusion-weighted MR Imaging in Guiding Selective Percutaneous Drainage of Postoperative Intra-abdominal Abscesses After Colorectal Resection

To determine whether DW-MRI is applicable in the evaluation of post-operative collections, and whether utilization of DW-MRI can enhance application of percutaneous drainage and prevent unnecessary drainage.

开始日期2017-02-15 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT01194531

IPSO Trial - Impact of Parental Support on Pregnancy Outcomes: A Multi-Center, Randomized, Open-Label Study to Evaluate the Implantation and Pregnancy Rates Following 24 Chromosome Aneuploidy Screening With Parental Support in Patients Undergoing In Vitro Fertilization (IVF)

Natera is recruiting patients for a research study evaluating pregnancy and implantation rates in women undergoing In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) and Preimplantation Genetic Screening (PGS). PGS is also referred to as Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis (PGD) for aneuploidy.

Healthy women undergoing IVF who are between the ages of 35 to 42 years are being recruited to participate in a randomized study.

The purpose of this study is to determine whether PGS- testing of embryos created during IVF for chromosomal abnormalities, prior to transfer to the uterus- improves pregnancy and implantation rates in patients when compared to patients whose embryos are not tested. PGS will be conducted using 24 Chromosome Aneuploidy Screening with Parental Support from Natera.

All subjects who qualify and enroll will receive discounted IVF medications (both TEST and CONTROL arms). If you become pregnant during the study, you will receive a small payment for providing information about your pregnancy and birth. If you are assigned to the TEST arm of the study you will receive free PGS.

Healthy women undergoing IVF who are between the ages of 35 to 42 years are being recruited to participate in a randomized study.

The purpose of this study is to determine whether PGS- testing of embryos created during IVF for chromosomal abnormalities, prior to transfer to the uterus- improves pregnancy and implantation rates in patients when compared to patients whose embryos are not tested. PGS will be conducted using 24 Chromosome Aneuploidy Screening with Parental Support from Natera.

All subjects who qualify and enroll will receive discounted IVF medications (both TEST and CONTROL arms). If you become pregnant during the study, you will receive a small payment for providing information about your pregnancy and birth. If you are assigned to the TEST arm of the study you will receive free PGS.

开始日期2010-09-01 |

申办/合作机构  Natera, Inc. Natera, Inc. [+1] |

100 项与 丹迪-沃克综合征 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 丹迪-沃克综合征 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 丹迪-沃克综合征 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

2,225

项与 丹迪-沃克综合征 相关的文献(医药)2025-12-31·Emerging Microbes & Infections

Distinct distribution of HEV-3 subtypes across humans, animals, and environmental waters in Sweden

Article

作者: Taslimi, Samaneh ; Tunovic, Timur ; Churqui, Marianela Patzi ; Nyström, Kristina ; Wang, Hao ; Andius, Linn Dahlsten ; Lagging, Martin

2025-12-31·Annals of Medicine

Impact of parathyroid gland classification on hypoparathyroidism following total thyroidectomy with central neck dissection for differentiated thyroid cancer

Article

作者: Zhang, Ping ; Wang, Bin ; Sheng, Qixuan ; Li, Wei ; Shan, Chengxiang ; Zhang, Wei ; Xu, Xinyun ; Rao, Wensheng ; Wang, Qiang ; Zha, Siluo ; Qiu, Ming

2025-12-31·European Journal of Psychotraumatology

Emotional vs. social loneliness and prolonged grief: a random-intercept cross-lagged panel model

Article

作者: O’Connor, Maja ; Vedder, Anneke ; Boelen, Paul A.

8

项与 丹迪-沃克综合征 相关的新闻(医药)2024-02-29

The news that your child has a health issue is unwelcome news to any parent, but the diagnosis of a rare disease brings a unique, complex set of challenges, and initiates a life-long journey of answer-seeking. As I awaited the birth of my son, instead of prepping the nursery, I was instead informed that he was likely to be born with a rare condition that could severely impact his quality of life. An MRI in the first hours of his life had shown he suffered two strokes in utero, and led physicians to a likely diagnosis of Greig syndrome, a rare genetic disease defined by skeletal deficiencies.

Having a rare disease, or being the family of a loved one with rare disease, can be a lonely feeling with much uncertainty about the future. There is often little literature on the condition, few advocacy groups, and limited or no treatment options or clinical trials for investigational treatments. But, when examined together, rare disease patients are anything but rare, and they are anything but alone. According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), 30 million Americans, or 10 percent of the population, have a rare disease. When you look across the globe, 3.5-5.9% of the world’s population, or 263-446 million people, have a rare disease. This Rare Disease Day is an opportunity to raise awareness of the challenges those living with a rare disease face, and why there’s reason to hope, thanks to advances in science that could potentially change the lives of millions of patients.

The rare disease gap

From diagnosis to treatment, the lifecycle of a rare disease is typically defined by more questions than answers. These questions started before my son was even born. Upon discovering he had extra toes on a late-stage ultrasound along with several abnormalities in his brain, diagnoses of trisomy 18, and rare diseases such as Dandy Walker syndrome and Greig syndrome were being discussed, as my husband and I scrambled to get a clear definition of these conditions and what they would mean for my son’s life – one more devastating than the next. The lack of research in rare disease and variances in symptoms makes it difficult for providers to make an informed diagnosis, which can take years. Even as someone who has spent their career in central nervous system (CNS) disorders, working in close quarters with neurologists and neurosurgeons and well-versed in complex medical speak, I was often at a loss of what the next steps of care held for my son, and I questioned every symptom in those early months of life.

Once a diagnosis is made, the assurance of an answer can be short lived – the path toward sustainable disease management and treatment varies widely by disease. There are approximately 7,000 rare diseases, and yet, only 5% have approved drugs. This presents a Catch-22 – the lack of precedent means rare diseases often do not have a clearly defined clinical trial roadmap or established endpoints, making scientific advancements difficult. The inherently small patient populations also make it difficult for researchers to devote resources to and implement a drug development program and conduct clinical trials. When research is pursued, developing rare disease treatments is a challenge due to their complex biology. Without treatment, patients and their families often need to manage these conditions with supportive care, such as a strict diet in the case of metabolic disorders.

The hope in mRNA medicine

Rare disease is often viewed as a forgotten, nonlucrative area of research. But, when companies put their valuable resources toward researching your disease that seems to only have dead-ends, it can feel like a sigh of relief – someone cares. Even if it doesn’t lead to solutions, knowing someone is trying can make a world of a difference, and ease the heavy uncertainty patients and their families operate under every day.

While mRNA became widely known during the pandemic because of its use in Covid-19 vaccines, the technology was investigated as a therapeutic long before then, and has particular potential for rare diseases. mRNA is a molecule that contains instructions that direct the cells to make proteins. Because many rare diseases are caused by a missing or dysfunctional protein, mRNA could help patients with rare metabolic disorders and potentially a variety of these protein and enzyme deficiencies. Now, scientists are investigating mRNA therapeutic candidates, and are seeing promising results to date. One of the biggest benefits to mRNA technology is its flexibility, allowing for slight variations to successfully target adjacent diseases.

Advancing the fight against rare disease

Despite needing a life-saving shunt to treat hydrocephalus in his first few months of life and multiple orthopedic surgeries in the years to follow, I am grateful that my fifteen-year-old son has largely lived a normal life with only small limitations. He’s one of the lucky ones. There are millions of families just like mine, waiting for the smoke to clear and for long-awaited answers.

Pursuing research in rare disease requires researchers to think differently about R&D, commit to a deep understanding of a patient’s lived experience, and build close relationships with the rare disease community. Our family motto is “never give up, never surrender.” Every rare disease patient is a warrior, but the fight doesn’t need to fought alone, and we’re grateful for the dedication to innovative, collaborative research that advances the battle.

2023-12-21

·今日头条

本期看点

① Freya获得3800万美元A轮融资

② 默沙东帕博利珠单抗胃癌适应证在中国获批

③ 默沙东帕博利珠单抗胃肠道癌症新适应证获欧盟批准

④ 华大基因子公司人粪便DNA甲基化检测产品取得医疗器械注册证

⑤ Biomerica幽门螺旋杆菌检测试剂盒获FDA 510(k)认证

⑥ 铭毅智造完成近亿元B++轮融资

① Freya获得3800万美元A轮融资

作者:

解读:Richard

来源:FINSMES

发布日期:2023-12-12

■ 内容要点

近日,临床阶段的生物科技公司Freya Biosciences宣布,获得了3800万美元(约合人民币2.71亿元)的A轮融资。Sofinnova Partners和OMX Ventures两家风投机构领衔了本次投资,参与投资的还有丹麦出口和投资基金、Angelini Ventures和Mike Jafar家族办公室等。

资金将用于帮助Freya Biosciences公司推进其阴道微生物免疫治疗产品临床开发,以及进一步开发其多组学数据挖掘技术平台。

Freya Biosciences公司在丹麦哥本哈根和美国波士顿分设两地,致力于解决女性健康问题,重塑阴道菌群平衡并使其恢复生殖能力。借助微生物深度测序技术和免疫标志物分类技术,Freya Biosciences公司正在积极开发阴道微生物免疫治疗产品,以改善一系列与生殖相关的免疫健康问题。

原文链接:

https://www.finsmes.com/2023/12/freya-biosciences-raises-38m-in-series-a-funding.html

② 默沙东帕博利珠单抗胃癌适应证在中国获批

作者:医药观澜

解读:orchid

来源:医药观澜

发布日期:2023-12-19

■ 内容要点

12月18日,默沙东宣布,中国国家药品监督管理局已批准其PD-1抑制剂帕博利珠单抗在中国的第12个新适应证上市,

联合含氟尿嘧啶类和铂类药物化疗用于局部晚期不可切除或转移性人表皮生长因子受体2(HER2)阴性胃或胃食管结合部腺癌患者的一线治疗。

帕博利珠单抗是一种人源化的抗PD-1单克隆抗体,可以阻断PD-1与其配体PD-L1、PD-L2的结合,进而激活T淋巴细胞。在中国,帕博利珠单抗此前已获批多项适应证,涵盖黑色素瘤、非小细胞肺癌、头颈部鳞状细胞癌、结直肠癌、食管癌、肝癌等。此次新适应证的获批是基于全球3期临床试验KEYNOTE-859的数据。

KEYNOTE-859试验数据显示,在预定的总生存期(OS)中期分析中,与单独化疗相比,随机接受帕博利珠单抗+化疗患者的OS、无进展生存期和客观缓解率均获得显著改善,患者的死亡风险降低了22%。中位OS为12.9个月,高于仅接受化疗患者的11.5个月。

安全性方面,在接受帕博利珠单抗治疗的患者中,有45%发生了严重不良反应。发生在>2%患者中的严重不良反应包括肺炎(4.1%)、腹泻(3.9%)、出血(3.9%)和呕吐(2.4%)。

原文链接:

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/TdP-wWiYGFMuxNYXzEQB_w

③ 默沙东帕博利珠单抗胃肠道癌症新适应证获欧盟批准

作者:默沙东

解读:Richard

来源:默沙东官网

发布日期:2023-12-18

■ 内容要点

12月18日,默沙东宣布旗下PD-L1抑制剂Keytruda(帕博利珠单抗),治疗胃肠道癌症两项新适应证获得欧盟批准。

两项新适应证分别为:

Keytruda与5-氟尿嘧啶和顺铂一线治疗局部晚期不可切除或转移性、HER2阴性胃或胃食管交界处腺癌PD-L1表达阳性患者(CPS评分≥1);Keytruda与吉西他滨和顺铂联用,一线治疗局部晚期不可切除或转移性胆道癌患者。

两项新适应证获批分别基于KEYNOTE-859和KEYNOTE-966关键3期临床结果。在KEYNOTE-859研究中,Keytruda联合用药方案显著改善了患者总生存期,死亡风险降低了22%;在KEYNOTE-966研究中,Keytruda联合用药方案也显著改善了患者总生存期,死亡风险降低了17%。

原文链接:

https://www.merck.com/news/european-commission-approves-mercks-keytruda-pembrolizumab-plus-chemotherapy-for-new-first-line-indications-in-advanced-her2-negative-gastric-or-gej-adenocarcinoma-in-tumors-expressin/

④ 华大基因子公司人粪便DNA甲基化检测产品取得医疗器械注册证

作者:澎湃财讯

解读:Johnson

来源:澎湃财讯

发布日期:2023-12-18

■ 内容要点

12月18日,深圳华大基因股份有限公司全资子公司华大数极生物科技(深圳)有限公司的人SDC2、ADHFE1、PPP2R5C基因甲基化联合检测试剂盒取得了国家药品监督管理局颁发的医疗器械注册证。

根据世界卫生组织癌症研究机构发布的2020年世界癌症报告,2020年中国结直肠癌发病人数56万人,位居所有癌种第二,死亡人数29万,位居所有癌种第五位。由于结直肠癌发展缓慢,定期进行早期筛查是预防结直肠癌的有效方式。粪便DNA检测由于检测性能优于传统粪便潜血检测,已经被纳入《中国结直肠癌筛查与早诊早治指南》和《早期结直肠癌和癌前病变实验诊断技术中国专家共识》。

本次获批的试剂盒产品用于体外定性检测人粪便样本中肠道脱落细胞的SDC2、ADHFE1和PPP2R5C基因的甲基化,以辅助结直肠癌早筛。

该试剂盒基于荧光定量 PCR 检测平台,具有肠癌和进展期腺瘤检测性能优异、检测通量配置灵活等特点,可满足临床用户的多样化和个性化需求。

原文链接:

https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_25696961

⑤ Biomerica幽门螺旋杆菌检测试剂盒获FDA 510(k)认证

作者:Biomerica

解读:Richard

来源:Yahoo! finance

发布日期:2023-12-18

■ 内容要点

12月18日,生物医学公司Biomerica宣布,

旗下幽门螺旋杆菌检测试剂盒Hp Detect(代号K232892),获得了FDA 510(k)认证。

胃癌是世界上第三大癌症相关死亡病因。据统计,80%的胃癌可归因于幽门螺旋杆菌感染。在美国,大约有35%的人群感染幽门螺旋杆菌,全世界约有一半的人口受到感染。不仅如此,幽门螺旋杆菌感染也是引起消化性溃疡的主要原因。

Hp Detect检测试剂盒采用了酶联免疫检测原理,使用患者粪便样本检测其中抗原成分,不仅可以用于检测幽门螺旋杆菌的有无,还可用于指导医师评估患者治疗后幽门螺旋杆菌感染情况。

原文链接:

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/biomerica-received-us-fda-510-124700643.html

⑥ 铭毅智造完成近亿元B++轮融资

作者:铭毅智造

解读:Richard

来源:铭毅智造官微

发布日期:2023-12-18

■ 内容要点

近日,深圳铭毅智造科技有限公司宣布完成近亿元B++轮融资。融资由连云港人才创投基金和江苏金桥私募基金等机构共同投资。

资金将主要用于铭毅智造在连云港建设规模化基因测序平台生产基地,推动测序仪量产,搭建市场推广网络,以及加速测序仪医疗器械注册申报等。

铭毅智造成立于2018年,专注于基因测序产业上游设备和试剂的研发制造,拥有专业的测序技术研发应用团队,掌握核心测序化学技术和相关专利,仅四年时间便推出了国际领先的单色荧光基因测序仪UniSeq2000。

目前,铭毅智造已完成UniSeq2000平台在tNGS、PGS、NIPT、CNV-seq、cfDNA相关临床应用的匹配和性能验证,并基于该平台打造出了临床本地化综合解决方案,多家单位已落地靶向病原体检测和遗传病筛查项目。后续,铭毅智造还将联合国内体外诊断伙伴不断推出新的本地化方案。

原文链接:

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/rXCRCNxPyffUz9uRMzA14A

临床3期上市批准免疫疗法

2022-11-29

LOS ANGELES--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Bionaut Labs, the company that uses microscale robots to revolutionize the treatment of central nervous system (CNS) diseases and disorders, today announced $43.2M in a Series B round of financing led by Khosla Ventures, bringing the company’s total financing raised to date to $63.2 million. Also participating in the round are new investors Deep Insight, OurCrowd, PSPRS, Sixty Degree Capital, Dolby Family Ventures, GISEV Family Ventures, What if Ventures, Tintah Grace and Gaingels, along with all existing investors - Upfront Ventures, BOLD Capital Partners, Revolution VC, and Compound.

Many diseases of the brain and central nervous system are hard to treat because it is difficult to deliver therapeutics beyond the blood-brain barrier and reach deep locations in the midbrain with precision. Through magnetic propulsion, Bionauts™ can navigate the depths of the human body to deliver drugs locally, generating efficacy and avoiding side effects and toxicity from systemically delivered drugs. By reaching the midbrain safely through novel routes, Bionaut Labs aims to develop solutions to treat the most debilitating conditions including Parkinson’s disease and Huntington's disease, malignant glioma and hydrocephalus.

Funds will be used to advance clinical development of the company’s lead programs against malignant glioma brain tumors and Dandy-Walker Syndrome (a rare pediatric neurological disorder). Funds will also support further development of its proprietary Bionaut™ treatment platform, allowing future expansion of clinical targets and progression through Bionaut’s two accelerated FDA designations. Bionaut Labs will release major pre-clinical data packages from IDE and IND enabling studies in 2023, with the goal of initiating human clinical trials in 2024.

“There has been a dearth of innovation around treatments for conditions that cause tremendous suffering, in large part because past failures have discouraged even the best of researchers,” said Michael Shpigelmacher, co-founder and CEO, Bionaut Labs. “Bionaut Labs remains committed to finding new ways to treat these devastating diseases, which are long overdue for a breakthrough.”

Bionaut Labs is co-founded by two robotics entrepreneurs, Michael Shpigelmacher and Aviad Maizels, who previously co-founded PrimeSense, the company that developed the facial recognition tech behind iPhone’s FaceID (sold to Apple in 2013 for approximately $400M). Its leadership and medical team consists of experts across robotics, neuroscience, biology and drug development.

“We are extremely excited about the transformative potential Bionaut presents in treating debilitating neurological disorders,” said Vinod Khosla, founder of Khosla Ventures. “Anatomically precise treatment will make traditionally-used methods seem archaic, and Bionaut is at the forefront of this movement.”

“Bionaut Labs tackles a complex pharmaceutical problem which many companies have failed to address in the past,” said Giammaria Giuliani, director of the GISEV Family Office. “As pioneers of micro-robotics for CNS treatment, the company enjoys a strong first-mover advantage and carries great promise.”

As neurodegeneration continues to grow in prevalence in the aging global population, Bionaut Labs offers unprecedented therapeutic access to the brain and other hard-to-reach locations in the body, diagnosing and treating diseases that were previously unreachable. Bionaut Labs will transform the way the biopharmaceutical industry develops treatments by offering a mechanism to engineer the therapeutic index for optimal efficacy and safety.

About Bionaut Labs

Bionaut Labs is a biotech company pioneering precision micro-technology with the deployment of microscale robots (Bionauts™), to remove the barriers of localized treatment and detection of diseases. Magnetic propulsion-controlled Bionauts navigate to deep locations in the human body and brain safely and precisely through non-linear 3D trajectories, making Bionaut Labs the first to access the midbrain through previously inaccessible anatomical routes. Bionauts can perform localized treatment, detection and precise medical procedures to deliver outcomes that were previously unattainable. The FDA has granted Bionaut Labs a Humanitarian Use Device designation for BNL-201, a micro-robot design to treat Dandy Walker Malformation, and an Orphan Drug Designation for BNL 101, a drug-device combination for treatment of malignant glioma. Led by a world-class team of medical, engineering, and drug development experts, Bionaut Labs’ is headquartered in Los Angeles, California, with additional R&D sites in Israel and at the Max Planck Institute in Germany. For more information, please visit www.bionautlabs.com.

孤儿药融资

分析

对领域进行一次全面的分析。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

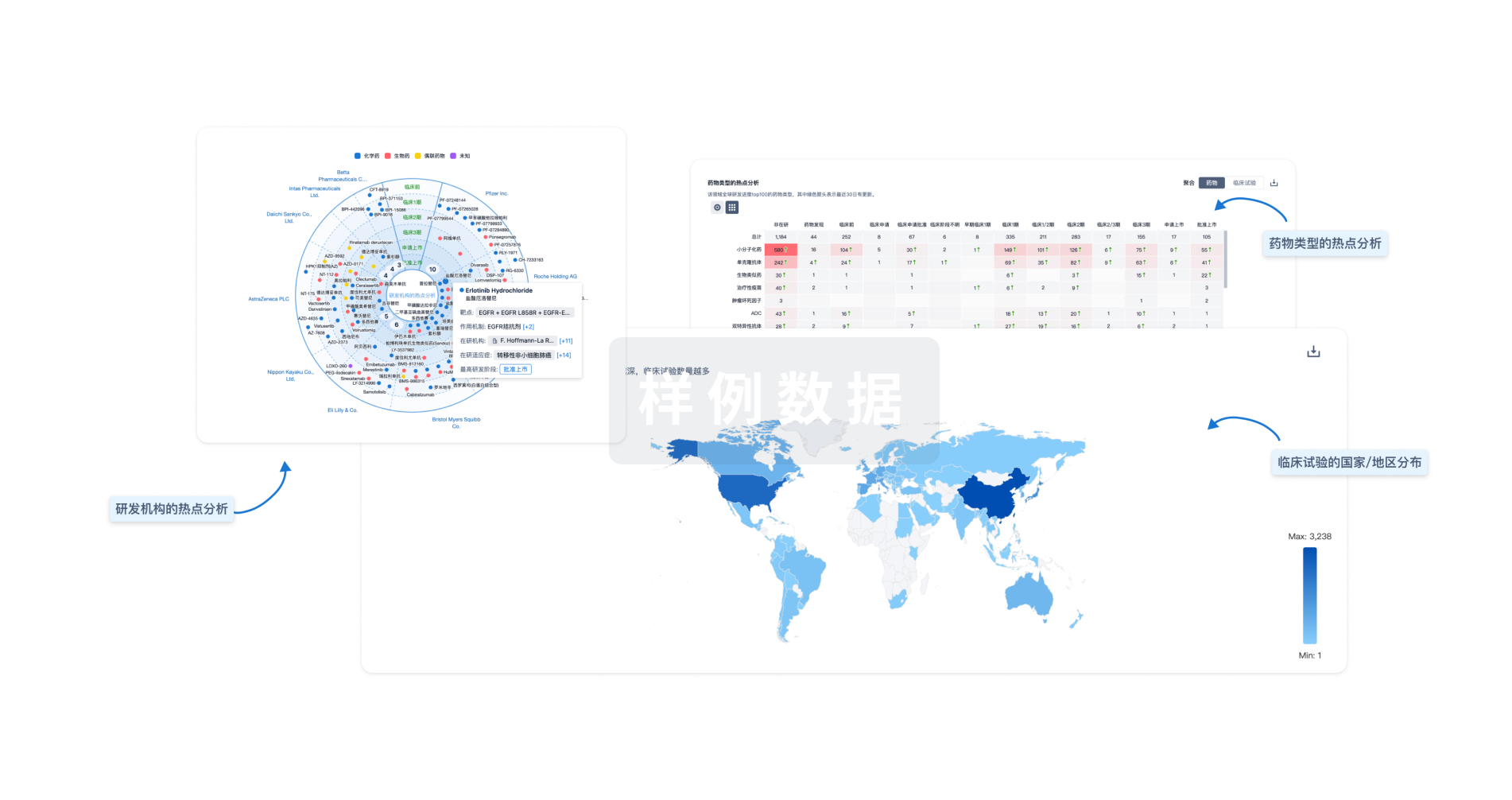

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用