预约演示

更新于:2026-02-07

GSK-1521498

更新于:2026-02-07

概要

基本信息

结构/序列

分子式C24H20F2N4 |

InChIKeyWIEDUMBCZQRGSY-UHFFFAOYSA-N |

CAS号1007573-18-3 |

关联

7

项与 GSK-1521498 相关的临床试验NCT01738867

A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Crossover Study to Evaluate the Influence of the A118G Polymorphism in the mu Opioid Receptor Gene (OPRM1) on Effects of GSK1521498 and Naltrexone on Physiological and Behavioural Markers of Brain Function in Healthy Social Drinkers

A total of at least 48 healthy subjects with a history of social drinking will be recruited into this single-centre, randomized, double-blind, cross-over study. Subjects will be genetically stratified to result in equal numbers of A118G 'AA' homozygotes (n=24) and A118G 'G' carriers (n=24).

Subjects will participate in all three treatment periods and will be randomized to receive each of the following for 5 days: Treatment A: Placebo, Treatment B: Naltrexone (NTX) 50 mg once daily (25 mg once daily for the first two days) and Treatment C: GSK1521498 10 mg once daily. A washout period will be of at least 14 days between treatments. Subjects will return for a follow-up visit 7-10 days after the final treatment session washout period has been completed.

Subjects will attend the clinical research unit on days 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 to monitor safety and tolerability for both drugs. Subjects will attend the clinical unit on days 4 and 5 for a two day assessment, using a series of pharmacodynamic measurements known to be sensitive to the effects of GSK1521498 and/or NTX: Functional brain response to alcohol and food cues; plasma cortisol; hedonic and consummatory eating behaviors; subjective response to an ethanol challenge; experimental pain threshold; and cognitive tests of attention bias towards alcohol and food cues.

Subjects will participate in all three treatment periods and will be randomized to receive each of the following for 5 days: Treatment A: Placebo, Treatment B: Naltrexone (NTX) 50 mg once daily (25 mg once daily for the first two days) and Treatment C: GSK1521498 10 mg once daily. A washout period will be of at least 14 days between treatments. Subjects will return for a follow-up visit 7-10 days after the final treatment session washout period has been completed.

Subjects will attend the clinical research unit on days 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 to monitor safety and tolerability for both drugs. Subjects will attend the clinical unit on days 4 and 5 for a two day assessment, using a series of pharmacodynamic measurements known to be sensitive to the effects of GSK1521498 and/or NTX: Functional brain response to alcohol and food cues; plasma cortisol; hedonic and consummatory eating behaviors; subjective response to an ethanol challenge; experimental pain threshold; and cognitive tests of attention bias towards alcohol and food cues.

开始日期2012-12-12 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT01366573

A Randomised, Double-Blind, Single-Dose, Four-Period Cross-Over Study to Determine the Effects of Alcohol on the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of GSK1521498 in Healthy Subjects

The aim of the study is to assess the safety and tolerability of GSK1521498 in combination with alcohol and to determine the amount of GSK1521498 and alcohol in your blood after you have been given these together. The study will also determine whether GSK1521498 will have an effect on alcohol liking and consumption.

开始日期2011-05-13 |

申办/合作机构  GSK Plc GSK Plc [+1] |

NCT01195792

A 35-Day, Multi-Centre, Randomised, Parallel-Group, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Proof of Concept Study to Investigate the Effects of GSK1521498 on Body Weight and Composition, Eating Behaviour and Related Brain Function, in Obese Subjects With Over-Eating Behaviours.

The purpose of this study is to determine whether GSK1521498 will cause weight loss in obese but otherwise healthy subjects with over-eating behaviours.

开始日期2010-09-01 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 GSK-1521498 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

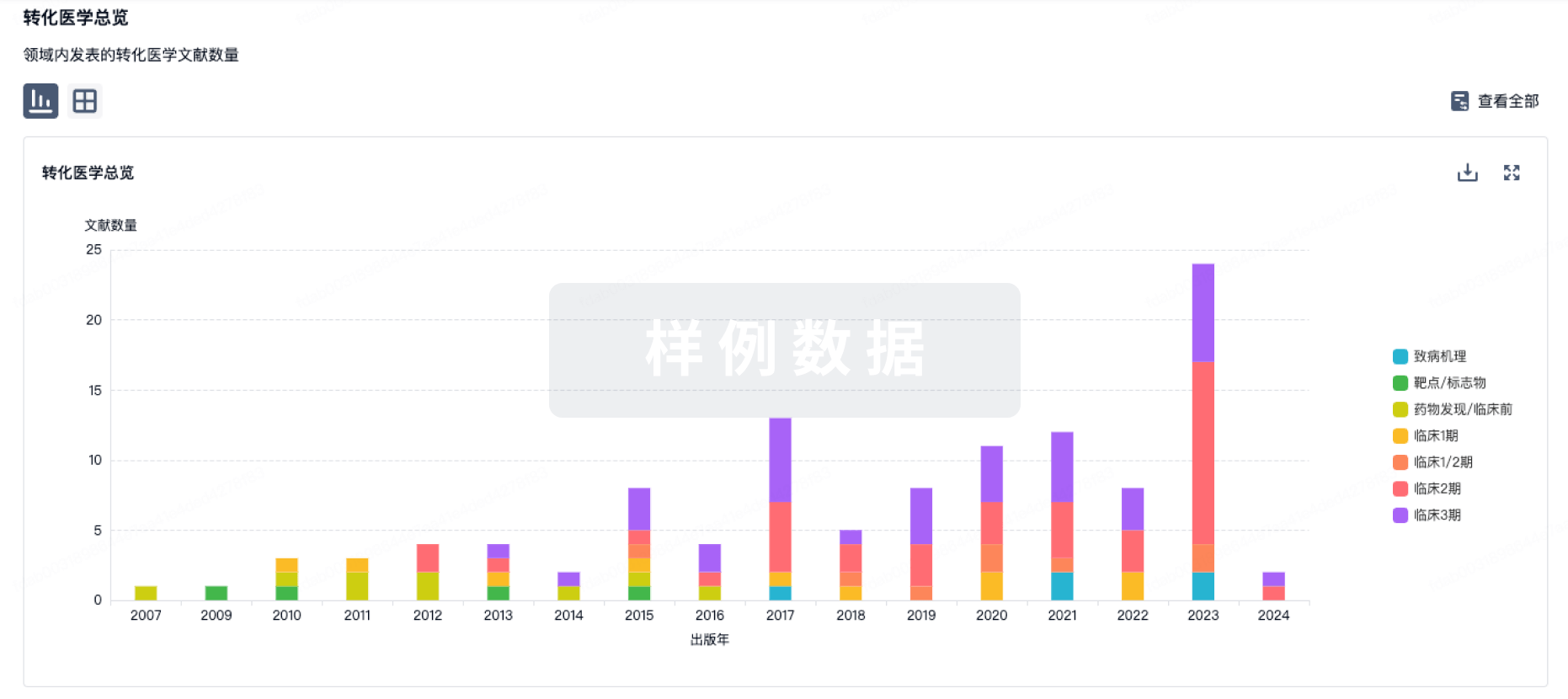

100 项与 GSK-1521498 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

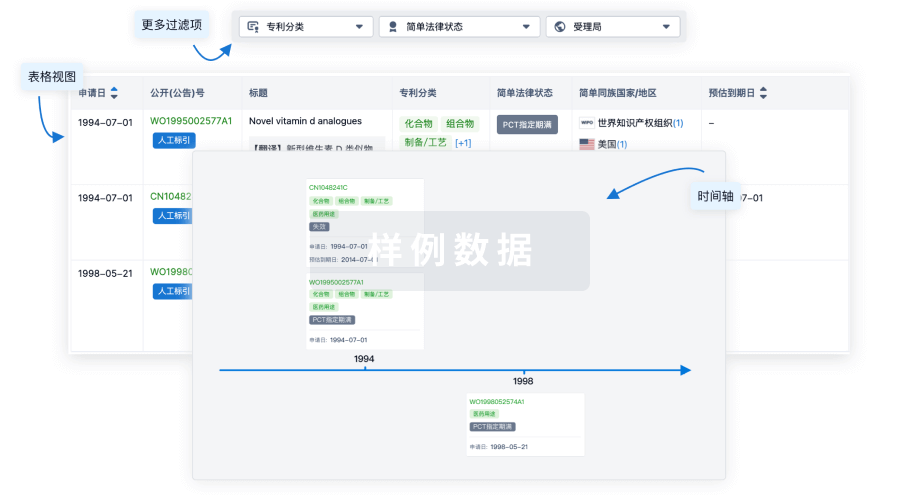

100 项与 GSK-1521498 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

24

项与 GSK-1521498 相关的文献(医药)2025-04-16·ACS Chemical Neuroscience

Toward a Small-Molecule Antagonist Radioligand for Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of the Mu Opioid Receptor

Article

作者: Saturnino Guarino, Dinahlee ; Schmitz, Alexander ; Graham, Thomas J. A. ; Plakas, Konstantinos ; Ho, Yi-Pei ; Mach, Robert H. ; Weng, Chi-Chang ; Lee, Hsiaoju ; Chia, Wai-Kit ; Li, Shihong ; Hou, Catherine ; Young, Anthony ; Hsieh, Chia-Ju

The opioid crisis is a catastrophic health emergency catalyzed by the misuse of opioids that target and activate the mu opioid receptor. Many traditional radioligands used to study the mu opioid receptor are often tightly regulated owing to their abuse and respiratory depression potential. Of those that are not regulated, a lack of opioid receptor subtype selectivity can cause confounding in interpreting results. In the present study, we sought to design and characterize a library of 24 antagonist ligands for the mu opioid receptor. Ligands were evaluated for the binding affinity, intrinsic activity, and predicted blood-brain barrier permeability. Several ligands demonstrated single-digit nM binding affinity for the mu opioid receptor while also demonstrating selectivity over the delta and kappa opioid receptors. The antagonist behavior of 1A and 3A at the mu opioid receptor indicate that these ligands would likely not induce opioid-dependent respiratory depression. Therefore, these ligands can enable a safer means to interrogate the endogenous opioid system. Based on binding affinity, selectivity, and potential off-target binding, [11C]1A was prepared via metallophotoredox of the aryl-bromide functional group to [11C]methyl iodide. The nascent radioligand demonstrated brain uptake in a rhesus macaque model and accumulation in the caudate and putamen. Naloxone was able to reduce [11C]1A binding, though the interactions were not as pronounced as naloxone's ability to displace [11C]carfentanil. These results suggest that GSK1521498 and related congeners are amenable to radioligand design and can offer a safer way to query opioid neurobiology.

2024-09-01·European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging

Total-body imaging of mu-opioid receptors with [11C]carfentanil in non-human primates

Article

作者: Tomita, Cosette ; Schmitz, Alexander ; Mach, Robert H ; Lee, Hsiaoju ; Hsieh, Chia-Ju ; Hou, Catherine ; Plakas, Konstantinos ; Dubroff, Jacob G

Abstract:

Purpose:

Mu-opioid receptors (MORs) are widely expressed in the central nervous system (CNS), peripheral organs, and immune system. This study measured the whole body distribution of MORs in rhesus macaques using the MOR selective radioligand [11C]carfentanil ([11C]CFN) on the PennPET Explorer. Both baseline and blocking studies were conducted using either naloxone or GSK1521498 to measure the effect of the antagonists on MOR binding in both CNS and peripheral organs.

Methods:

The PennPET Explorer was used for MOR total-body PET imaging in four rhesus macaques using [11C]CFN under baseline, naloxone pretreatment, and naloxone or GSK1521498 displacement conditions. Logan distribution volume ratio (DVR) was calculated by using a reference model to quantitate brain regions, and the standard uptake value ratios (SUVRs) were calculated for peripheral organs. The percent receptor occupancy (%RO) was calculated to establish the blocking effect of 0.14 mg/kg naloxone or GSK1521498.

Results:

The %RO in MOR-abundant brain regions was 75–90% for naloxone and 72–84% for GSK1521498 in blocking studies. A higher than 90% of %RO were observed in cervical spinal cord for both naloxone and GSK1521498. It took approximately 4–6 min for naloxone or GSK1521498 to distribute to CNS and displace [11C]CFN from the MOR. A smaller effect was observed in heart wall in the naloxone and GSK1521498 blocking studies.

Conclusion:

[11C]CFN total-body PET scans could be a useful approach for studying mechanism of action of MOR drugs used in the treatment of acute and chronic opioid use disorder and their effect on the biodistribution of synthetic opioids such as CFN. GSK1521498 could be a potential naloxone alternative to reverse opioid overdose.

2024-08-07·ACS Chemical Neuroscience

Machine Learned Classification of Ligand Intrinsic Activities at Human μ-Opioid Receptor

Article

作者: Oh, Myongin ; Shen, Jana ; Shen, Maximilian ; Stavitskaya, Lidiya ; Liu, Ruibin

Opioids are small-molecule agonists of μ-opioid receptor (μOR), while reversal agents such as naloxone are antagonists of μOR. Here, we developed machine learning (ML) models to classify the intrinsic activities of ligands at the human μOR based on the SMILES strings and two-dimensional molecular descriptors. We first manually curated a database of 983 small molecules with measured Emax values at the human μOR. Analysis of the chemical space allowed identification of dominant scaffolds and structurally similar agonists and antagonists. Decision tree models and directed message passing neural networks (MPNNs) were then trained to classify agonistic and antagonistic ligands. The hold-out test AUCs (areas under the receiver operator curves) of the extra-tree (ET) and MPNN models are 91.5 ± 3.9% and 91.8 ± 4.4%, respectively. To overcome the challenge of a small data set, a student-teacher learning method called tritraining with disagreement was tested using an unlabeled data set comprised of 15,816 ligands of human, mouse, and rat μOR, κOR, and δOR. We found that the tritraining scheme was able to increase the hold-out AUC of MPNN models to as high as 95.7%. Our work demonstrates the feasibility of developing ML models to accurately predict the intrinsic activities of μOR ligands, even with limited data. We envisage potential applications of these models in evaluating uncharacterized substances for public safety risks and discovering new therapeutic agents to counteract opioid overdoses.

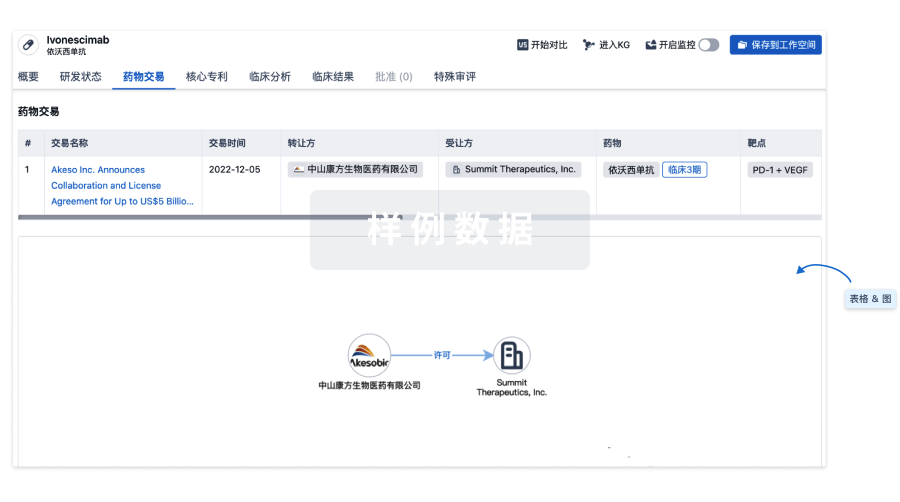

100 项与 GSK-1521498 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

外链

| KEGG | Wiki | ATC | Drug Bank |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | - |

研发状态

临床结果

临床结果

适应症

分期

评价

查看全部结果

| 研究 | 分期 | 人群特征 | 评价人数 | 分组 | 结果 | 评价 | 发布日期 |

|---|

No Data | |||||||

登录后查看更多信息

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

核心专利

使用我们的核心专利数据促进您的研究。

登录

或

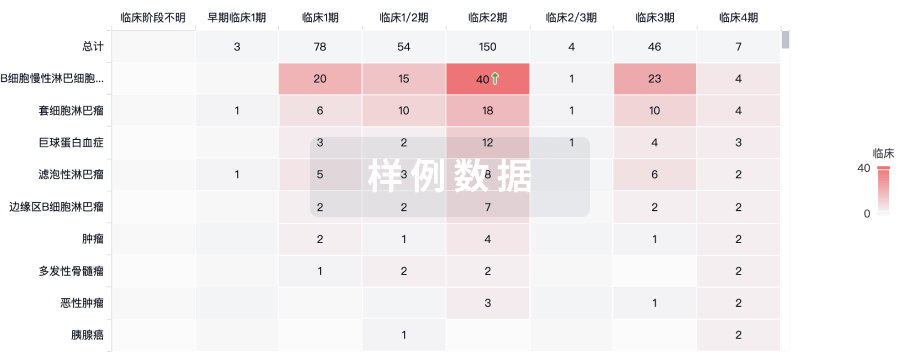

临床分析

紧跟全球注册中心的最新临床试验。

登录

或

批准

利用最新的监管批准信息加速您的研究。

登录

或

特殊审评

只需点击几下即可了解关键药物信息。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用