预约演示

更新于:2025-05-07

Nematode Infections

线虫感染

更新于:2025-05-07

基本信息

别名 DISEASES DUE TO NEMATODA、Disease due to Nematoda、Infection, Nematode + [37] |

简介 Infections by nematodes, general or unspecified. |

关联

44

项与 线虫感染 相关的药物靶点 |

作用机制 谷氨酸门控氯离子通道调节剂 |

原研机构 |

非在研适应症 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 美国 |

首次获批日期2018-06-13 |

靶点- |

作用机制- |

在研机构 |

原研机构 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 中国 |

首次获批日期2004-04-30 |

264

项与 线虫感染 相关的临床试验NCT06800248

A Phase III Single-center, Randomized, Double-Blinded, Parallel-group, Active Controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of a Single Dose of Emodepside Compared to Multiple Doses of Mebendazole in Adolescent and Adult Participants With Soil-transmitted Helminthiasis

This study aims to assess the efficacy and safety of emodepside compared to mebendazole in adults and adolescents infected with T. trichiura, either as single infection or co-infections with hookworm and/or A. lumbricoides.

开始日期2025-08-01 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT06736691

A Phase III Single-center, Randomized, Double-blinded, Parallel-group, Active-controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of a Single Dose of Emodepside Compared to Multiple Doses of Mebendazole in Adolescent and Adult Participants With Soil-transmitted Helminthiasis

This study aims to assess the efficacy and safety of emodepside compared to mebendazole in adults and adolescents infected with T. trichiura, either as single infection or co-infections with hookworm and/or A. lumbricoides.

开始日期2025-05-01 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT06720259

A Randomised, Single-Blinded Phase II Trial to Assess the Efficacy, Safety and Acceptability of Oxantel Pamoate in Comparison to Mebendazole for Trichuris Trichiura Infections in Children Aged 2-12 Years

This study aims to provide evidence on the efficacy, safety and acceptability of the new, chewable formulation of oxantel pamoate administered as a single dose or multiple doses, compared to mebendazole in children infected with T. trichiura. This study will involve children aged 2-12 years, since an infection with T. trichiura occurs often in children.

开始日期2025-04-16 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 线虫感染 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 线虫感染 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 线虫感染 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

33,849

项与 线虫感染 相关的文献(医药)2025-12-31·Veterinary Quarterly

First assessment of the prevalence of

Trichinella

in backyard-raised pigs in Central-Southern Chile

Article

作者: Crisóstomo-Jorquera, Vanesa ; Henríquez, AnaLía ; Guzmán-Faúndez, Javiera ; Landaeta-Aqueveque, Carlos

2025-10-01·Parasitology International

Effects of wood creosote on anisakiasis: A Japanese traditional medicine as a potential tool against Anisakis larva infection

Article

作者: Sugiyama, Hiromu ; Shiroyama, Mitsuko ; Miura, Takanori ; Pereira, Caroline Donzeli ; Shimokawa, Chikako

2025-07-01·Revista Española de Patología

Pulmonary angiostrongyliasis: Two cases of atypical manifestations of Angiostrongylus costaricensis in Guatemala

Article

作者: Orozco, Roberto ; Santis-Mejía, Juan Carlos ; Argueta, Victor

88

项与 线虫感染 相关的新闻(医药)2025-04-25

引言自2003年成立以来,得益于与全球伙伴的合作,DNDi已交付了13种针对被忽视的疾病的全新治疗方法,挽救了大量的被忽视疾病患者的生命。但对于大部分人而言,这些救命药的发现,仍是个“迷”。在本期推送中,DNDi研究员&《新药研发解密》栏目主讲人Fanny Escudié将以生动有趣的方式,为你揭示科学家们如何使用最先进的科学技术来改善世界各地数百万被忽视疾病患者的生活。《新药研发解密》2 高通量筛选技术:测试上百万分子,为被忽视的疾病寻找药物《新药研发解密》3 先导化合物优化的魔法:研究人员如何设计分子来治疗被忽视的疾病点击“阅读原文”,了解更多关于被忽视疾病药物研发的尖端技术及其背后的故事。关于DNDi被忽视疾病药物研发倡议组织(DNDi)是一个以病患需求为出发点的非营利性药物研发组织。DNDi主要为被忽视的疾病患者研发新的治疗方法,其中包括昏睡病、南美锥虫病、利什曼病、淋巴丝虫病、足菌肿、儿童艾滋病/艾滋病以及丙型肝炎的治疗方法。DNDi同时也在协调ANTICOV临床试验,为非洲的轻度至中度新冠肺炎(COVID-19)患者寻找治疗方法。自2003年成立以来,DNDi迄今已交付了13种全新的治疗方案,其中包括用于治疗利什曼病的新药物组合、两种固定剂量的抗疟药,首次成功研发的新化学实体药物非昔硝唑(fexinidazole)用于治疗昏睡病,以及通过南南合作研发的丙肝药物拉维达韦(ravidasvir),旨在为全球丙肝患者提供可负担的药物选择。*点击下方图片,了解更多有关DNDi的介绍。

2025-03-08

引语

一位来自肯尼亚偏远村庄的孕妇与内脏利什曼病的抗争,揭开了全球医药研发领域存在已久的隐蔽鸿沟——女性患者的用药困境。从临床试验的“玻璃门”到医疗服务递送的“被忽视”,无数像Mary一样的女性因为生理差异而无法获得救命药。DNDi正与全球的合作伙伴一起弥合性别差距,提升孕产妇的健康水平,让健康之光照亮每一个人,不论性别。

生死时速:当孕妇感染内脏利什曼病

在肯尼亚西部波克特县的隆盖莱村,一位养育四个孩子的妈妈——Mary Alamak又怀孕了。她如同从前一样,每天盼望着孩子的平安出生,但事与愿违。不知为何,怀孕的Mary最近不仅没有增重,反而在短时间内从80公斤骤减到45公斤。她日渐虚弱,甚至无法独立行走,到哪儿都需要有人搀扶。

"我的身体状况一天不如一天,吃不下任何食物,持续高烧,而且胃部剧痛难忍",Mary回忆道。与此同时,她每时每刻都在担心胎儿的健康,而对失去孩子的恐惧和担忧,让她陷入抑郁。

康复的Mary在讲述她的故事。[图源:Paul Kamau/DNDi]

为了找到她生病的原因,家人陪她来到医院进行检查。医生为她进行了疟疾、艾滋病毒和布鲁氏菌等一系列检测后,发现所有结果均呈阴性。接下来的一个月,Mary备受病痛煎熬,而医生也在继续努力寻找她的病因。终于,Mary为医生提供了新的线索——她的丈夫曾出现相同症状并接受过针对内脏利什曼病的治疗。

终于,在将Mary确诊为内脏利什曼病患者后,医生立即为她启用脂质体两性霉素B进行治疗——这是治疗内脏利什曼病患者的二线药物,也用于孕妇、65岁以上老人和两岁以下儿童等特殊人群。然而,这种药物必须冷藏保存在2-8℃环境中,并且持续10天的疗程费用高昂,这不管对于医院还是患者来说都是挑战。

幸运的是,Mary最终获得了这项安全有效的治疗,并恢复了健康。

被忽视的患者:临床试验中的性别差距

尽管Mary的故事发生在十多年前,但在今天,仍有许多像Mary一样的孕期女性面临感染“被忽视的热带病“的风险,并且女性常常成为”被忽视的患者“。

DNDi科学家Borna

Nyaoke-Anoke医生表示,作为一名研究者,令她最痛苦的经历就是在被忽视的热带病领域目睹女性被忽视。”足菌肿(另一种被忽视的热带病)会导致患者毁容,使女性无法工作,而她们往往受害最深——因为她们倾向于隐匿病情,不去寻求治疗和护理。其他人认为这是巫术所致,因为他们不了解这种疾病。"

Borna医生正在为一名足菌种患者进行诊治。[图源:Mamadou Diop-DNDi]

事实上,女性患者不仅仅在诊断和治疗等医疗服务递送阶段被忽视,早在药物研发的临床试验阶段,性别差距就已经显著存在。女性常被排除在临床试验外,导致难以开发出孕期或哺乳期女性可用的安全、有效且可负担的药物。

来自尼日利亚的妇产科教授Hadiza Galadanci曾指出,“截至2020年,全球有28.7万名女性死于孕产相关原因。而在临床试验中排除孕妇会导致在应对怀孕等特定场景下药物和技术的缺乏。“

泰国Siriraj临床研究中心(SICRES)创始主任Kulkanya Chokephaibulkit教授表示,”在临床试验中,青春期女性比男性更少。一些临床研究会有意避免女性参与,尤其是药物交互作用的有关研究。纳入青春期女性参与临床研究可能在知情同意、污名和社会压力、伦理考虑、隐私保密、依从性(如中途怀孕)、父母同意等方面遭遇挑战。“

尽管充满挑战,但科学家们认为,推进临床试验中的性别平等对提升女性乃至全人群的健康水平都有重要意义。DNDi 东南亚区域办公室主管Vanessa

Daniel指出:“若女性在临床试验中被忽视,那么她们的健康需求也会被遗忘,我们应该倡导真正反映真实的多元化世界的研究。“

向右滑动查看更多 >>

科学家们谈临床试验中性别平等的重要性。

破局密钥:性别响应型药物研发

可以看到,女性在传统生物医学研发中的特殊医疗需求长期被忽视。而女性和女童往往受被忽视的热带病影响尤为严重,却常常因为照护角色限制而无法及时获得诊疗服务。此外,尽管女性占全球人口半数,但其在药物开发中始终是被忽视的群体。

为了颠覆这一持续存在且危害严重的现状,DNDi承诺实施性别响应型药物研发最佳实践(如推动临床试验中女性参与者比例的提升,在保障安全的前提下系统性纳入孕期及哺乳期女性受试者),系统性地消除治疗可及性的性别壁垒,支持孕产妇健康。与此同时,DNDi也与伙伴机构合作,基于四大洲的经验,建立文化特异性障碍分析模型,并从药物研发早期阶段就纳入性别公平的考量。

目前,DNDi的研究人员已经公开发表了一项关于纳入可能在临床试验过程中怀孕的女性人群的安全伦理框架。制定了(含潜在妊娠人群),该框架从伦理层面规范了安全采集新药审批所需数据的实践准则。通过将性别因素主动纳入临床研究与项目设计,并提高治疗可及性,DNDi能够推动知识进步,最终增加获批用于治疗被忽视的热带病的药物数量——涵盖所有人群,包括孕妇及育龄女性。

临床试验安全伦理框架提议。图源:公开发表论文《Inclusion of women susceptible to and becoming pregnant in preregistration clinical trials in low- and middle-income countries: A proposal for neglected tropical diseases》

值得注意的是,满足女性特殊医疗需求的研究高度依赖女性科研人才的深度参与。而目前女性在研究领域的代表性往往不足。为推进女性参与科学研究以促进公平的药物研发,DNDi成立跨部门性别响应型研发与可及性指导委员会,并在建立公平薪酬体系、提供平等的职业发展培训与晋升通道以及在招聘过程中消除隐性偏见等方面不断努力。

值此国际妇女节之际,我们呼吁医药研发领域及医疗服务领域的伙伴们重视性别差距,并以共同努力来重塑医药研发的未来:

✅ 在临床研究与项目设计中纳入性别因素✅ 提升临床试验中女性参与者比例✅ 支持女性科研人才参与药物研发

未来,每个生命都能平等享有健康,救命药不再有“性别密码“。

如果你喜欢这篇文章,欢迎分享给对临床试验中的性别公平、健康公平等议题感兴趣的朋友或同事。还可以点击“阅读原文“,在DNDi的官网了解更多你感兴趣的内容。

关于DNDi

被忽视疾病药物研发倡议组织(DNDi)是一个以病患需求为出发点的非营利性药物研发组织。DNDi主要为被忽视的疾病患者研发新的治疗方法,其中包括昏睡病、南美锥虫病、利什曼病、淋巴丝虫病、足菌肿、儿童艾滋病/艾滋病以及丙型肝炎的治疗方法。DNDi同时也在协调ANTICOV临床试验,为非洲的轻度至中度新冠肺炎(COVID-19)患者寻找治疗方法。

自2003年成立以来,DNDi迄今已交付了13种全新的治疗方案,其中包括用于治疗利什曼病的新药物组合、两种固定剂量的抗疟药,首次成功研发的新化学实体药物非昔硝唑(fexinidazole)用于治疗昏睡病,以及通过南南合作研发的丙肝药物拉维达韦(ravidasvir),旨在为全球丙肝患者提供可负担的药物选择。

*点击下方图片,了解更多有关DNDi的介绍。

临床研究

2025-02-22

Tiki Barber gave me a brief glimmer of hope this week.

“There’s an elephant in the room,” the former New York Giants football star said, perched in a leather chair, talking with GSK CEO Emma Walmsley in front of over 500 pharma executives, lobbyists, consultants and other industry members.

Barber was speaking just a few hours after Robert F. Kennedy Jr. delivered his welcome address at HHS headquarters. I had flown down to Washington that Tuesday for the inaugural PhRMA Forum, hoping to hear the drug industry’s plans for Trump’s second term.

Finally

, I thought,

maybe Tiki will bring up the talk of the town

.

Barber described a different elephant: the frustration of dealing with the layers and middlemen that get between patients and their medicines.

That was indicative of how the three-hour PhRMA Forum went. Pharma CEOs and other speakers stuck to safe, Trump-friendly topics on the stage. In the process, they studiously avoided weighing in on the chaotic flurry of actions in the Beltway.

PhRMA CEO Stephen Ubl called Trump the “disrupter-in-chief,” while Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla argued Trump’s opportunities will outweigh the risks for pharma. Gilead CEO Dan O’Day trotted out a variation on Kennedy’s “Make America Healthy Again” slogan, saying everyone here shared a commitment to “making America a healthier place for all.”

They praised Trump as a status-quo challenger, but didn’t discuss what the last month has shown that to actually mean. Trump has proposed major cuts to NIH research grants, installed a longtime anti-vaccine advocate to lead HHS, and overseen mass firings at agencies like the FDA and CDC.

In his speech to HHS on Tuesday, Kennedy made it clear what he meant by making America healthy again. His priorities as health secretary include launching investigations into childhood vaccine schedules and anti-depression drugs as ways of fighting chronic disease, he said.

Over the forum’s three hours, I didn’t hear a single shout-out in defense of the NIH, FDA, or CDC. (I also requested interviews on the forum’s sidelines with the CEOs of Merck, Pfizer, GSK, and Novartis. Their spokespeople either didn’t respond or said they were unavailable.)

The motivation driving this selective silence seems clear: Isn’t it better to have a seat at the table?

We’ll see how the gambit plays out. The CEOs may view their recent meeting at the White House as evidence of success. The price of admission, though, seems to be the industry’s most powerful leaders biting their tongues on defending some basic scientific principles, like vaccine safety, and institutions, like the NIH.

Few details have emerged from that closed-door White House sit-down. Much clearer was

the torrent of boos

that greeted Bourla when he was later introduced by the president before a Trump-supporting crowd in the East Room. That’s the latest reminder of how public distrust of the healthcare industry has deteriorated into public hatred.

This isn’t the only option in the playbook. When Roy Vagelos ran Merck from 1985 to 1994, he became pharma’s leading voice. He was a champion of investing in research and occasionally took steps that placed the long-term sustainability of the industry over what’s best for next quarter’s earnings, like a then-unprecedented donation of a Merck drug to treat river blindness in millions of people.

Under Vagelos, Merck repeatedly was ranked as America’s most admired corporation — not just in pharma, but across all industries. That’s an unimaginable reality today.

Vagelos wasn’t the only Merck CEO to show leadership. Ken Frazier resigned from a presidential manufacturing council during Trump’s first term, objecting to Trump’s comments on blaming “many sides” for a fatal confrontation involving white supremacists in Charlottesville, VA.

Frazier said he had “a responsibility to take a stand.” Where is the Vagelos or Frazier of today?

— Andrew

(This is Post-Hoc, our latest newsletter with analysis and dispatches from our journalists. To sign up for future editions,

click here

.)

分析

对领域进行一次全面的分析。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

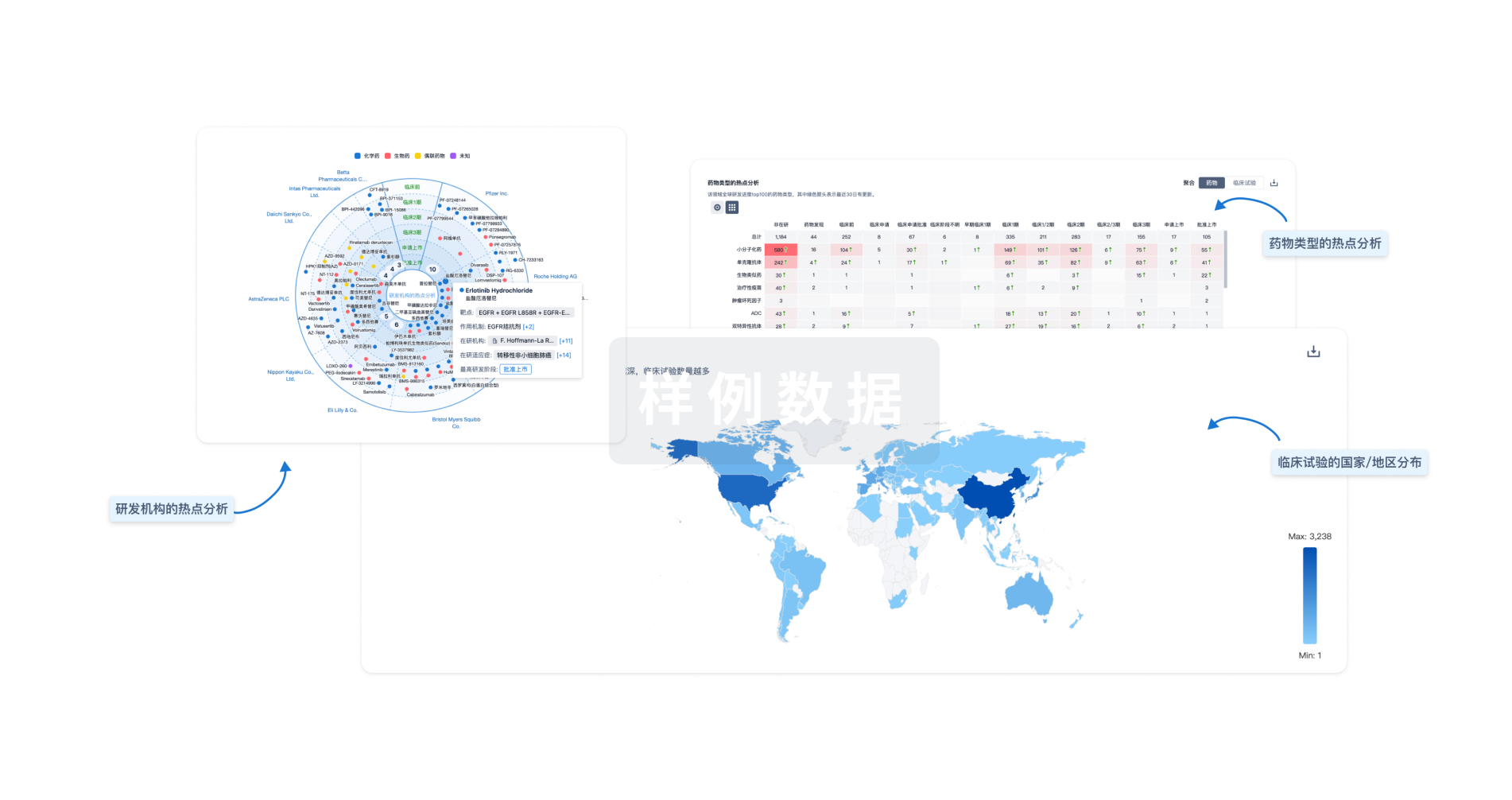

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用