预约演示

更新于:2026-02-04

Pegozafermin

更新于:2026-02-04

概要

基本信息

原研机构 |

在研机构 |

非在研机构- |

最高研发阶段临床3期 |

首次获批日期- |

最高研发阶段(中国)- |

特殊审评优先药物(PRIME) (欧盟)、突破性疗法 (美国) |

登录后查看时间轴

结构/序列

Sequence Code 431553327

来源: *****

关联

7

项与 Pegozafermin 相关的临床试验NCT06419374

A Phase 3 Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Pegozafermin in Subjects With Compensated Cirrhosis Due to Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis (MASH) (ENLIGHTEN-Cirrhosis)

The study will assess the efficacy and safety of pegozafermin administered in participants with compensated cirrhosis due to MASH (biopsy-confirmed fibrosis stage F4 MASH [previously known as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, NASH]).

开始日期2024-05-24 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT06318169

A Phase 3 Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Pegozafermin in Subjects With Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis (MASH) and Fibrosis

The study will assess the efficacy and safety of 2 dose regimens of pegozafermin compared to placebo for the treatment of liver fibrosis stage F2 or F3 in adult participants with MASH.

开始日期2024-03-13 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT05852431

A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Pegozafermin in Subjects With Severe Hypertriglyceridemia (SHTG): The ENTRUST Study

To determine the effect of Pegozafermin on fasting serum triglyceride levels in subjects with Severe Hypertriglyceridemia (TG ≥500 to ≤2000 mg/dL) after 26 weeks of treatment.

开始日期2023-06-15 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 Pegozafermin 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

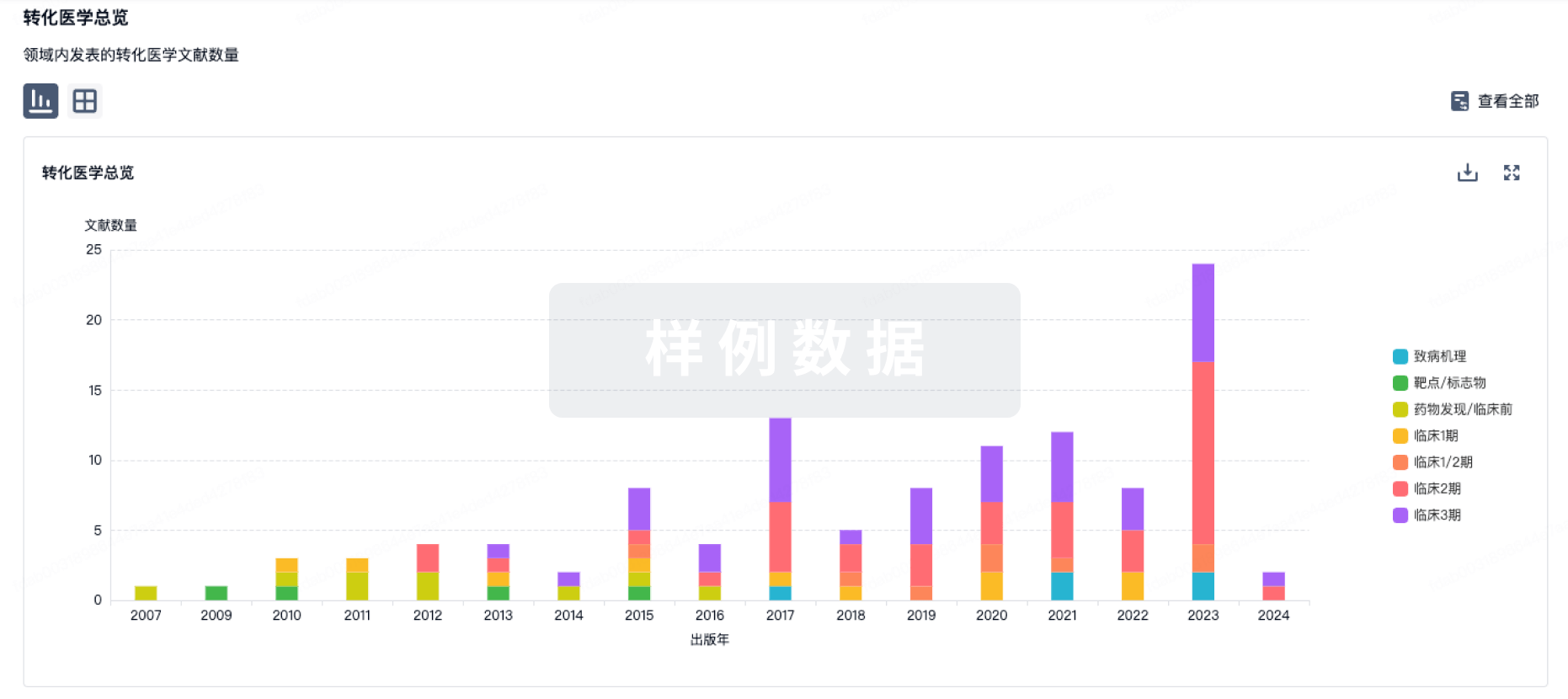

100 项与 Pegozafermin 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

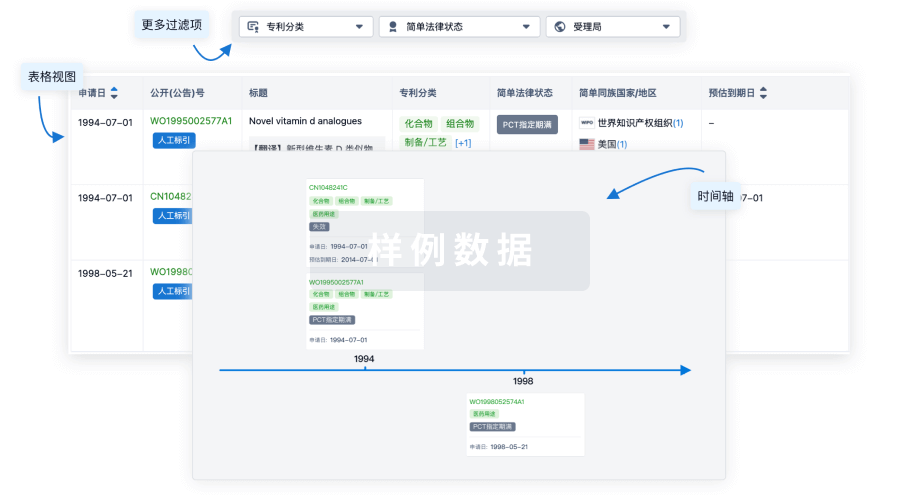

100 项与 Pegozafermin 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

19

项与 Pegozafermin 相关的文献(医药)2026-01-01·HEPATOLOGY

Comparative efficacy of pharmacologic therapies for MASH in reducing liver fat content: Systematic review and network meta-analysis

Review

作者: Nah, Benjamin ; Seko, Yuya ; Ramadoss, Vijay ; Takahashi, Hirokazu ; Noureddin, Mazen ; Ng, Cheng Han ; Xiao, Jieling ; Nakajima, Atsushi ; Koh, Benjamin ; Sim, Benedix Kuan Loon ; Teng, Margaret ; Huang, Daniel Q. ; Danpanichkul, Pojsakorn ; Teo, Chong Boon ; Gunalan, Shyna Zhuoying ; Law, Michelle ; Lim, Mei Chin ; Muthiah, Mark ; Wijarnpreecha, Karn ; Loomba, Rohit ; Tan, En Ying

Background and Aims::

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is a leading cause of liver disease. Dynamic changes in MRI proton-density-fat fraction (PDFF) are associated with MASH resolution. We aimed to determine the relative efficacy of therapeutic agents for reducing hepatic fat, assessed by MRI-PDFF.

Approach and Results::

In this systematic review and network meta-analysis, we searched MEDLINE and Embase from inception until December 26, 2023, for published randomized controlled trials comparing pharmacological interventions in patients with MASH that assessed changes in MRI-PDFF. The

primary outcome

was the absolute change in MRI-PDFF. The secondary outcome was a ≥30% decline in MRI-PDFF. A surface under-the-curve cumulative ranking probabilities (SUCRA) analysis was performed. Of 1550 records, a total of 39 randomized controlled trials (3311 participants) met the inclusion criteria. For MRI-PDFF decline at 24 weeks, aldafermin (SUCRA: 83.65), pegozafermin (SUCRA: 83.46), and pioglitazone (SUCRA: 71.67) were ranked the most effective interventions. At 24 weeks, efinopegdutide (SUCRA: 67.02), semaglutide + firsocostat (SUCRA: 62.43), and pegbelfermin (SUCRA: 61.68) were ranked the most effective interventions for achieving a ≥30% decline in MRI-PDFF.

Conclusions::

This study provides an updated, relative rank-order efficacy of therapies for MASH in reducing hepatic fat. These data may help inform the design and sample size calculation of future clinical trials and assist in the selection of combination therapy.

2026-01-01·JOURNAL OF PHARMACOLOGY AND EXPERIMENTAL THERAPEUTICS

Efficacy and safety of fibroblast growth factor 21 analogs in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease and metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis

Review

作者: Abouelmagd, Khaled ; Taha, Nouran A ; Fareed, Areeba ; Keshk, Menna ; Taha, Amira Mohamed ; Ali, Shujaat ; Hasan, Mohammed Tarek ; Khan, Misha ; Abdelkader Saed, Sara Adel ; Abdeljawad, Marwa Muhammed

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease has emerged as a global public health concern. Fibroblast growth factor 21, a liver hormone, is gaining interest because of its ability to regulate metabolism and improve metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. In this network meta-analysis, we investigated the efficacy of these treatments in treating metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. A comprehensive search was conducted across electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science, till August 2025. We used R software to analyze data using a random effects model. Heatmaps were used to visualize the included interventions' ranking. We included 9 clinical trials comprising 1277 patients. Among them, 284 received efruxifermin, 263 received pegbelfermin, 151 received pegozafermin, 65 received efimosfermin, 139 received MK-3655, and 375 received a placebo. Pegozafermin and efruxifermin were effective in improving liver fibrosis (RR, 3.89-3.93, P < .05; RR, 2.23-1.91, P < .05, respectively), whereas the other interventions did not yield statistical significance. Efimosfermin α, efruxifermin, and pegozafermin improved different metabolic parameters, including adiponectin, hemoglobin A1c, and non-high-density lipoprotein. However, no significant differences were observed in body weight and low-density lipoprotein. For liver enzymes, efimosfermin α had the greatest reduction of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, whereas efruxifermin was most effective in reducing γ-glutamyl transferase levels. The odds of adverse events were higher in pegozafermin, efimosfermin, and efruxifermin groups, mainly attributed to mild to moderate gastrointestinal adverse events. In conclusion, efruxifermin and pegozafermin are promising therapeutic options with a tolerable adverse event profile; meanwhile, efimosfermin α showed promising results in improving metabolic parameters, with histologic results yet to be published. SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT: This meta-analysis evaluates the efficacy of fibroblast growth factor 21 analogs in improving metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Efruxifermin and pegozafermin were the most significant in improving liver fibrosis; moreover; significant improvements in some metabolic parameters were observed with efimosfermin α, efruxifermin, and pegozafermin.

2025-12-01·HEPATOLOGY

Comparison of pharmacological therapies in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis for fibrosis regression and MASH resolution: Systematic review and network meta-analysis

Review

作者: Antunes, Vanio L.J. ; Huang, Daniel Q. ; Souza, Matheus ; Al-Sharif, Lubna ; Loomba, Rohit

Background and Aims::

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is a leading cause of liver disease. With the advent of multiple therapeutic targets in late-phase clinical drug development for MASH, there is a knowledge gap to better understand the comparative efficacy of various pharmacological agents. We conducted an updated network meta-analysis to evaluate the relative rank order of the different pharmacological agents for both fibrosis regression and MASH resolution.

Approach and Results::

We searched PubMed and Embase databases from January 1, 2020 to December 1, 2024, for published randomized controlled trials comparing pharmacological interventions in patients with biopsy-proven MASH. The co-primary endpoints were fibrosis improvement ≥1 stage without MASH worsening and MASH resolution without worsening fibrosis. We conducted surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) analysis. A total of 29 randomized controlled trials (n=9324) were included. Pegozafermin, cilofexor + firsocostat, denifanstat, survodutide, obeticholic acid, tirzepatide, resmetirom, and semaglutide were significantly better than placebo in achieving fibrosis regression without worsening MASH. Pegozafermin (SUCRA: 79.92), cilofexor + firsocostat (SUCRA: 71.38), and cilofexor + selonsertib (SUCRA: 69.11) were ranked the most effective interventions. Pegozafermin, survodutide, tirzepatide, efruxifermin, liraglutide, vitamin E + pioglitazone, resmetirom, semaglutide, pioglitazone, denifanstat, semaglutide, and lanifibranor were significantly better than placebo in achieving MASH resolution without worsening fibrosis. Pegozafermin (SUCRA: 91.75), survodutide (SUCRA: 90.87), and tirzepatide (SUCRA: 84.70) were ranked the most effective interventions for achieving MASH resolution without worsening fibrosis.

Conclusions::

This study provides updated rank-order efficacy of MASH pharmacological therapies for fibrosis regression and MASH resolution. These data are helpful to inform practice and clinical trial design.

218

项与 Pegozafermin 相关的新闻(医药)2026-02-02

·氨基观察

氨基观察-创新药组原创出品

作者 | 武月

曾经的肿瘤霸主正从“青黄不接”的焦虑中走出。

罗氏这个昔日的肿瘤霸主,交出了一份营收增长7%、制药业务增长9%的稳健答卷。更重要的是,数字背后是一幅“重整河山”的清晰图景。Phesgo、Xolair、Ocrevus、Hemlibra、Vabysmo和Polivy六大引擎全开,不仅覆盖了老药下滑的窟窿,也拉动着罗氏的制药业务继续增长。

在肿瘤腹地,Phesgo以48%的增速证明HER2防线依然坚固;在血液瘤战场,Polivy正攻城略地,复兴之势持续。罗氏CEO更是反复提及的“不会遭遇专利悬崖”,因为2030年之前将推出19款新药,其中 16 款具备重磅炸弹潜力,9 款销售峰值将突破 30 亿美元。

这其中,乳腺癌领域诞生新王牌giredestrant,罗氏对其信心满满;尤其是在兵家必争的减重领域,罗氏再次高调宣布要成为“第三极”。

当罗氏将百亿美元赌注押向肥胖、阿尔茨海默病等慢性病领域时,一场关乎未来十年的战略豪赌已然展开。成功,则河山永固;若有差池,下一个悬崖或许已在视野之中。

无论如何,罗氏让我们在行业史上最严峻专利悬崖面前看到了一种思路:保持战略定力,敢于突破舒适区,才能在不确定性中找到新的增长答案。毕竟,在创新药的战场上,从来没有永恒的王者,只有不断进化的幸存者。

/ 01 /

乳腺癌新王牌

2025年,罗氏的制药业务收入为476.69亿瑞士法郎(约576.27亿美元),同比增长9%。

细看罗氏的制药业务神经科学、免疫、眼科领域的增长更为明显,分别同比增长11%、12%和10%。不过,对于曾经的肿瘤霸主罗氏来说,更重要的是,肿瘤作为最大收入来源,实现了连续八个季度的增长,2025年贡献239.38亿瑞士法郎,同比增长6%。

Phesgo、Xolair、Ocrevus、Hemlibra、Vabysmo 五大重磅产品以及正在加速爆发的Polivy,成为拉动罗氏制药业务的绝对核心,2025年合计新增销售额为36亿瑞士法郎,完全覆盖了Avastin、Herceptin等专利到期产品7亿瑞士法郎的销售额下滑。

其中,表现最亮眼的莫过于Phesgo。2025年销售增幅高达48%,这款将帕妥珠单抗与曲妥珠单抗“双靶合一”的皮下注射制剂,凭借剂型革新的优势,正在全球加速放量。罗氏在财报电话会议上表示,Phesgo全球转化率持续攀升,目前已达54%,正朝着60%的新目标稳步迈进。

换句话说,随着转化率的提升,Phesgo还将保持这种增长态势。从曲妥珠单抗一直到帕妥珠单抗、恩美曲妥珠单抗,再到Phesgo,HER2靶点一直是罗氏的重中之重。

尽管目前HER2领域竞争十分激烈,但罗氏对未来依然充满信心,明确表示其HER2产品线将在2026年达到约90亿瑞士法郎的峰值,然后平稳过渡至2030年,并维持约40亿瑞士法郎的尾部收入。这40亿瑞士法郎主要来自Phesgo(30亿)和Kadcyla(10亿)。

当然,作为曾经的乳腺癌霸主,罗氏的野心不止于守成。HER2之外,其正全力开拓ER+(激素受体阳性)乳腺癌市场。这也是乳腺癌最常见的亚型,ER阳性乳腺癌约占全部病例的70%,且高达三分之一的早期乳腺癌患者在接受辅助内分泌治疗期间或之后,会经历复发,许多患者由于安全性或耐受性问题不得不提前中断或停止治疗,这些局限性凸显了对更有效、耐受性更好的治疗方案的需求。

而罗氏认为其口服SERD药物Giredestrant,成为ER阳性乳腺癌治疗新一线疗法的潜力十足。尽管公司官方给出的峰值销售指引是“超过30亿美元”,但管理层的实际预期显然要高得多。罗氏CEO Teresa Graham在电话会上多次强调、重申Giredestrant成为ER新一线药物,尤其是在辅助用药领域的广阔前景。

罗氏的信心来源于两项关键III期胜利:用于晚期二线治疗的evERA研究,以及2025年底公布阳性结果的、用于早期辅助治疗的lidERA研究。后者尤其重要,它首次证明口服SERD在降低早期乳腺癌复发风险上显著优于标准内分泌治疗,覆盖了约55%的辅助治疗人群。

对此,Teresa Graham难掩兴奋:“你不可能看了lidERA的结果而不相信(改变标准疗法)会成为现实。”她进一步描绘蓝图:在高达200-300亿美元的ER+乳腺癌市场中,辅助治疗占三分之二,Giredestrant的目标是成为新的内分泌治疗基石。

但“药王”之路从无坦途。SERD赛道竞争日渐白热化,礼来、阿斯利康等巨头皆有重兵布局。更关键的挑战在于临床医生的接受度。有医生指出,将口服SERD定位为早期疾病新标准,路径必然漫长且严格;另外lidERA试验对照组未纳入当前标准的“AI(芳香化酶抑制剂)+CDK4/6抑制剂”方案,说服力不足。能否在激烈竞争中证明临床价值,将是 Giredestrant能否一改乳腺癌格局,成为罗氏新王牌的关键。

/ 02 /

血液瘤持续复兴

对于罗氏来说,其在血液领域的领军地位毋庸置疑,但自利妥昔单抗专利过期后,其在自己最为强势的血液学领域,节节败退。血友病双抗Emicizumab和CD79b靶向ADC Polivy的崛起,阻止了这一颓势。

“血液瘤业务正在复兴”,这一罗氏在2024年抛出的判断,在2025年继续得到了验证。

全年血液学产品线销售额达86亿瑞士法郎,同比增长15%,成为制药业务中增速最快的领域之一,而Polivy正是这场“复兴运动”的核心推手。

2021年8月,一项Polivy联合化疗方案(R-CHP)的关键临床3期研究显示:Polivy+R-CHP一线治疗弥漫性大B细胞淋巴瘤(DLBCL),将患者疾病进展、复发或死亡风险降低了27%。

经历重重监管审批,2023年4月Polivy获FDA批准,与R-CHP联用一线治疗DLBCL患者,成为20年来首个DLBCL的一线治疗方案。自此,Polivy快速放量,2023年全球销售额实现翻倍增长,突破10亿美元。

2025年,Polivy销售额达14.7亿瑞士法郎,同比增长38%,更实现两个关键里程碑:一是在美国IPI 2-5级(中高危)DLBCL患者中,成为最常用的一线治疗方案;二是仅一线DLBCL适应症销售额就突破10亿瑞士法郎。

目前,其一线市场占比约36%,全球治疗患者超6万。而罗氏曾预计,Polivy将占据一线DLBCL约65%的市场份额。这意味着,Polivy还将继续增长。

与此同时,罗氏在双抗赛道的布局也开始收获果实。CD20/CD3双抗Columvi在三线及以上DLBCL治疗中快速渗透,2025年销售额达2.88亿瑞士法郎,同比增长75%;另一款双抗Lunsumio则在滤泡性淋巴瘤领域表现亮眼,皮下制剂获批后销售额同比增长68%至 1.14亿瑞士法郎。

不过,Columvi被FDA泼了一盆冷水,驳回其二线上市申请。这也导致这些后线产品的峰值预期有所下降,由10亿瑞士法郎降至数亿。

对于罗氏来说,更重要的是,这些产品共同构成了其在血液瘤领域多层次、差异化的火力矩阵。在昔日的王牌利妥昔单抗专利到期后,罗氏通过迭代创新,用更精准、便捷的疗法重新站住脚跟,完成了从单抗时代到ADC与双抗时代的引擎切换。

/ 03 /

百亿美金豪赌慢病“炸弹”

在经历专利悬崖痛击后,罗氏决定拓展业务边界,不能将所有鸡蛋放在同一个篮子里。

2025年研发日上,罗氏明确表示,过去十年,公司已经成功在多发性硬化症、血友病等新疾病领域占有一席之地,下个十年将进入阿尔茨海默症、高血压、肥胖等大型疾病领域。

资金流向是最诚实的宣言。2025年以来,罗氏达成了超过20笔交易,总金额逾200亿美元,其中绝大多数集中在代谢和自免领域。这也是罗氏历史上首次在肿瘤之外的业务投入更多资金。

其中,减重是罗氏布局的重心。目标是成为肥胖领域的全球前三玩家,罗氏在2025年财报电话会上再次强调这一目标。为此,罗氏斥重金构建了差异化减重管线:

2023年底以27亿美元收购Carmot,获得GLP-1/GIP双受体激动剂CT-388、口服GLP-1 受体激动剂CT-996;2025年3月,与Zealand Pharma达成53亿美元的合作,仅首付款就高达16.5亿美元,引进长效胰淀素类似物Petrelintide;9月又以35亿美元收购89bio,将FGF21类似物Pegozafermin收入囊中,进军MASH赛道。

总之,罗氏认为其建立的产品组合,能够非常容易地满足减重患者可能拥有的几乎所有需求。这或许就是罗氏希望在减重领域成为全球前三的底气。

按照其规划, 2030 年前推出19 款新药,其中 17款具备重磅炸弹潜力,1款峰值预计在 20 亿美元至 30 亿美元间,10 款突破破 30 亿美元,大多来自肥胖、高血压、脂肪肝、阿尔茨海默病等慢病领域。

仅减重领域,就有望为罗氏贡献 2 个年销售 30 亿美元以上的产品(组合),分别是 GLP-1 药物组合(CT-388、CT-868、CT-996)和长效胰淀素类似物 Petrelintide。

其中,GLP-1/GIP双受体激动剂CT-388日前已经启动治疗伴2型糖尿病的肥胖或超重患者的3期研究,并公布了减重2期临床的积极结果:第48周时,接受治疗的肥胖或超重患者,实现了22.5%的安慰剂校正体重下降,且未出现体重下降平台期。此外,CT-388与Petrelintide还有联用的潜力。

不止肥胖,罗氏在MASH、高血压等慢病领域也布下重兵。Pegozafermin的MASH适应症已进入3期临床,预计2027年公布结果;从Alnylam引进的siRNA疗法Zilebesiran,高血压治疗的临床也已进入3期,有望实现半年一次给药的突破;TL1A单抗 Afimkibart则在IBD和MASH领域同步推进。

这些都是罗氏眼中的峰值超30亿美元的重磅炸弹。也正因此,罗氏CEO在谈及BD策略时显得底气十足,由于没有迫在眉睫的专利悬崖,罗氏“没有压力去为了买而买”,但会“密切关注中国正在发生什么”。

未来几年,将是罗氏这些重磅炸弹的密集验证期,这场豪赌交给时间来验证。

/ 04 /

总结

创新药的世界没有永恒的王者,只有不断的进化。

从曾经的“肿瘤霸主”到如今的“多赛道玩家”,罗氏重整河山之路,本质上是一场巨头的自我革新。

当然,一切雄心仍需接受科学与市场的最终检验。Giredestrant能否重塑乳腺癌格局,成为其新王牌?重金押注的GLP-1产品能否在诺和诺德与礼来的统治下杀出重围?这些问题的答案,将决定罗氏绘制的这幅新蓝图,究竟是海市蜃楼,还是真正可持续的江山远景。

PS:欢迎扫描下方二维码,添加氨基君微信号交流。

专利到期财报

2026-01-22

·药时代

出海机会来了!

寻找PCSK9小分子抑制剂产品,全球权益,目前所处阶段不限。

请感兴趣的公司立即联系:药时代BD团队

BD@drugtimes.cn

正文共:850字

预计阅读时间:4分钟

2026年1月21日,国家药品监督管理局(NMPA)药品审评中心(CDE)官网显示,礼来的GIP/GLP-1双受体激动剂替尔泊肽拟纳入突破性疗法,用于治疗代谢相关性脂肪性肝病(MASH)。

临床数据积极

2024年6月,礼来公布了一项替尔泊肽治疗MASH患者的II期SYNERGY-NASH研究的详细结果。该研究纳入190例活检证实为MASH的受试者(伴或不伴有2型糖尿病),伴2期或3期纤维化。

有效性估计目标显示,替尔泊肽5mg、10mg和15mg组分别有51.85%、62.8%和73.3%的受试者在52周治疗后,肝脏组织学上达到了MASH完全缓解且纤维化程度未恶化,而安慰剂组这一比例为13.2%,达到了研究的主要终点。该数据在2024年欧洲肝病研究学会年会(EASL)上公布,并同时发表于《新英格兰医学杂志》(NEJM)。

在次要终点中,有效性估计目标显示,替尔泊肽5mg、10mg和15mg组中,分别有59.1%、53.3%和54.2%的受试者实现≥1阶段肝脏纤维化程度的改善,且未发生MASH程度恶化,而安慰剂组这一比例为32.8%。其他次要终点显示,替尔泊肽与体重改善、肝脏损伤血液标志物以及肝脏脂肪、炎症和纤维化的生物标志物的改善相关。所有剂量组均显示了对肝脏纤维化具有临床意义的治疗有效性。

MASH药物研发进入“快车道”

MASH是一种严重且呈进展性的代谢性肝病,若不加以有效控制,可进一步发展为肝硬化甚至肝癌。据统计,全球MASH患者数已超过2.5亿,其中美国约2200万人受其影响。长期以来,该疾病缺乏特效药物,患者主要依赖生活方式干预及部分尚未获批的药物进行管理。

近年来,MASH药物研发进入快速发展阶段,靶点研究从传统的单一代谢通路拓展至多机制协同调控,覆盖代谢调节、炎症抑制和纤维化改善等多个病理环节。其中,甲状腺激素受体β(THR-β)和胰高血糖素样肽-1(GLP-1)靶点已有药物获批上市。

全球首款MASH新药是Madrigal公司开发的Rezdiffra,于2024年3月获FDA上市。作为一款THR-β选择性激动剂,它通过增加线粒体生物合成来增强肝细胞处理脂肪的能力,从而减少肝脏脂肪堆积。上市仅五个完整季度,Rezdiffra销售额就已超过 10 亿美元。

随后在2025年8月,诺和诺德的重磅疗法Wegovy(2.4 mg司美格鲁肽)也获得FDA的加速批准,成为首个获批用于治疗MASH的胰高血糖素样肽-1(GLP-1)疗法。加速批准基于ESSENCE试验的第一部分结果,该研究显示司美格鲁肽能显著改善肝纤维化且不加重脂肪性肝炎,同时在改善脂肪性肝炎方面也优于安慰剂,且未伴随肝纤维化进展。

除此之外,其他作用机制如FXR激动剂、DGAT2抑制剂、FGF21类似物等也在积极推进中。

FXR激动剂可通过调节胆汁酸代谢和改善胰岛素敏感性发挥作用,但因其副作用在一定程度上限制了临床应用。例如奥贝胆酸曾因副作用问题终止开发,后续药物如FXR314等仍处于临床试验阶段。

DGAT2抑制剂通过抑制二酰基甘油酰基转移酶2,降低肝脏甘油三酯合成,直接改善肝脏脂肪变性。例如反义寡核苷酸药物ION224在其IIb期研究中,使60%高剂量组患者肝脏健康状况显著改善,且疗效与体重变化无关,为尤其非肥胖型MASH患者提供了新思路。

FGF21类似物在2025年成为行业关注焦点,多家大型药企通过并购布局该领域:葛兰素史克于7月收购波士顿制药,获得efimosfermin alfa;罗氏于9月收购89bio,获得其Pegozafermin;诺和诺德于10月以52亿美元将Akero Therapeutics及其III期核心产品Efruxifermin(EFX)收入囊中。这些FGF21靶向药物均主要针对中重度肝纤维化及肝硬化患者,旨在满足该群体迫切的治疗需求。

参考资料:

1.CDE官网

2.5000万美元首付款!Madrigal 买下辉瑞“弃药”

3.MASH药物:靶点突破与百亿美元赛道的竞速狂欢(公众号:汇聚南药)

封面图/摘要图来源:药时代

跨越“死亡谷”:从本土高难度类器官到全球谈判桌,中韩联合改写ALS治疗规则

2026-01-22

强生2025财报:传奇CAR-T大卖18.87亿美元!

2026-01-22

股价暴涨近166%!自免AD领域杀出黑马

2026-01-21

死亡/复发风险降低49%!Moderna宣布癌症疫苗联合K药5年随访结果

2026-01-21

版权声明/免责声明

本文为汇编文章。

本文仅作信息交流之目的,不提供任何商用、医用、投资用建议。

文中图片、视频、字体、音乐等素材或为药时代购买的授权正版作品,或来自微信公共图片库,或取自公司官网/网络,部分素材根据CC0协议使用,版权归拥有者,药时代尽力注明来源。

如有任何问题,请与我们联系。

衷心感谢!

药时代官方网站:www.drugtimes.cn

联系方式:

电话:13651980212

微信:27674131

邮箱:contact@drugtimes.cn

点击查看更多精彩内容!

临床2期突破性疗法加速审批上市批准

2026-01-22

·煎茶笔记

昨天为大家分享了JMP大会上150多家公司的PPT!

JPM 2026 PPT (全) - Ai 知识库

那么这些公司说了些什么呢?最热门的领域在哪里?各家的未来之星是什么?

今天我们就来看看大模型是如何分析的:

一、肿瘤学(Oncology)

肿瘤学是2026年J.P. Morgan医疗健康大会上最突出、被提及最频繁的疾病领域。

几乎所有涉及肿瘤领域的头部生物制药公司,如恒瑞医药、百济神州、辉瑞、再生元、吉利德、百时美施贵宝、艾伯维、诺华、BioNTech、Exelixis等,均在演讲中重点讨论了其癌症药物管线。

讨论内容涵盖了从新机制探索到具体癌种应用的全景,包括抗体偶联药物(ADC)、双特异性抗体、CAR-T细胞疗法、基因疗法、小干扰RNA(siRNA)、肿瘤疫苗等多种前沿技术,在肺癌、乳腺癌、前列腺癌、血液肿瘤及消化道肿瘤等领域的临床试验进展和商业化前景,共同描绘了肿瘤治疗创新的未来图景。

治疗模式创新与多元化竞争

行业的焦点已从单一疗法转向治疗模式的多元化探索。

百济神州在其展示中,将ADC、双抗、mRNA技术、细胞与基因治疗等并列视为驱动当前创新的核心力量。恒瑞医药则进一步强调了为关键适应症提供 “一站式解决方案” 的战略,并依托其强大的“工具箱”——涵盖免疫治疗、小分子靶向药、ADC和癌症疫苗等平台——积极探索联合治疗的无限可能,旨在实现治疗的协同效应,提升临床获益。核心公司与产品管线进展

多家公司公布了密集的2026年里程碑计划,使其成为肿瘤领域的“催化剂之年”。恒瑞医药

展示了其行业领先的AXC/ADC技术平台的持续迭代,并计划在2026年提交第二代(新型载荷)和第三代(双载荷)ADC新药的临床试验申请。其核心产品包括:全球首个进入III期临床的KRAS G12Di抑制剂HRS-4642(2026年数据更新)、在多个适应症处于III期阶段的HER2 ADC SHR-A1811和Claudin 18.2 ADC SHR-A1904(预计2026-2027年数据读出及申报上市)。

百济神州

的核心产品泽布替尼已成为全球BTK抑制剂市场的领导者,并计划在2026年公布其联合疗法用于一线套细胞淋巴瘤的III期数据。同时,其索托拉西布计划于2026年在美国获批用于复发/难治性套细胞淋巴瘤,并启动与泽布替尼联用治疗一线慢性淋巴细胞白血病的III期研究。

传奇生物

的CARVYKTI®(西达基奥仑赛)在多发性骨髓瘤治疗中展现了显著的疗效,2025年销售额达到17亿美元,2026年的战略重点是继续巩固其市场领导地位并推进下一代细胞疗法。

Coherus BioSciences

将2026年定位为 “数据丰富的关键年份” ,将披露其核心产品LOQTORZI®(PD-1抑制剂)以及其他在研资产的关键临床数据。BioNTech

展示了丰富的肿瘤学管线,2026年将有超过十项关键里程碑,涉及trastuzumab pamitecan(HER2 ADC,用于子宫内膜癌)、gotistobart(双抗,用于乳腺癌)、BNT113(PD-1单抗,用于非小细胞肺癌)等多个项目的晚期临床数据读出。

中国药企全球化与领导力显现

一个显著趋势是中国创新药企正在加速全球化进程。恒瑞医药明确提出 “加速全球业务拓展” 的战略,通过香港上市、布局全球临床试验、推进国际上市申请等方式展现其全球领导力,并声称其原研药管线规模已位居全球第二。这标志着中国药企从本土创新走向全球竞争的新阶段。联合疗法成为核心探索方向

联合用药是提升疗效和克服耐药的关键策略。这一趋势在多家公司的展示中得以体现。例如,恒瑞医药展示了“I/O(免疫疗法)+I/O”以及“多靶点联合”(如PARP抑制剂氟唑帕利联合抗血管生成药阿帕替尼)方案优异的临床数据。Exelixis等公司也强调了探索其核心产品与其他机制药物联用的潜力。

总结而言,2026年JPM大会上的肿瘤学领域呈现出创新高度活跃、技术路径并行、开发全球化、治疗策略协同的鲜明特点。从ADC、细胞疗法的持续突破,到联合方案的深入探索,再到中国力量的强势崛起,行业正共同推动肿瘤治疗向更精准、更有效、可及性更高的未来迈进。

二、代谢性疾病—肥胖与2型糖尿病

继肿瘤学之后,代谢性疾病,特别是肥胖症与2型糖尿病,成为2026年J.P. Morgan医疗健康大会上被讨论最频繁的领域之一。

以GLP-1类药物为引爆点,行业正迅速迭代,探索超越现有疗法的多元技术路径,竞争焦点从单纯的减重效果扩展到改善代谢、保留肌肉、提升便利性及探索全新机制,旨在满足巨大的、尚未被完全满足的全球健康需求。技术路径的“第二浪”与多元化竞逐

大会的讨论显示,对肥胖和糖尿病的治疗探索已不满足于单靶点GLP-1激动剂。下一代疗法正沿着多靶点协同、给药方式创新和颠覆性新机制三个方向齐头并进,形成了鲜明的技术迭代趋势。多靶点与口服制剂

在GLP-1单靶点基础上,GLP-1/GIP双靶点激动剂、GLP-1/GIP/GCG三靶点激动剂已成为主流研发方向,旨在通过协同作用实现更优的减重和控糖效果。同时,为提升患者依从性,口服剂型的研发成为关键,力图打破注射给药的限制。新机制探索

更前沿的机制如小干扰RNA (siRNA) 被引入减重领域。其核心理念是实现持久高效的减重,并可能避免肌肉流失,这被视为对当前GLP-1类药物缺点的潜在解决方案。同时,口服小分子靶向全新通路(如menin)也被用于改善2型糖尿病的β细胞功能,从根源上干预疾病。

联合疗法前景

与肿瘤学领域类似,联合疗法被视为提升疗效和克服耐药的重要策略。已有公司计划探索不同作用机制药物的联合使用,以期实现“1+1>2”的临床获益。关键公司管线与2026年里程碑

多家生物制药公司将其在代谢疾病领域的核心资产与近期催化剂作为展示重点,2026年被普遍视为数据读出和监管申请的关键年份。

公司

核心产品/资产

技术特点/适应症

2026年关键里程碑恒瑞医药

HRS9531

GLP-1/GIP双靶点激动剂(注射)

已递交中国上市申请。

HRS-7535

口服GLP-1受体激动剂

处于III期临床试验阶段。

HRS-4729

GLP-1/GIP/GCG三靶点激动剂

处于I期临床试验阶段。Oneness Biotech

SNS851

用于持续减重的siRNA药物,新机制

作为下一代肥胖创新药重点展示,旨在实现持久高效减重且不损失肌肉。

Fespixon®/Bonvadis®

糖尿病足溃疡(DFU)创新药

预计2026年在欧盟获得CE认证。Biomea Fusion

Icovamenib

口服menin抑制剂,用于改善2型糖尿病β细胞功能

计划2026年第一季度启动两项II期研究;预计2026年第四季度获得26周数据。

BMF-650

GLP-1小分子减重药物

I期研究结果预计2026年第二季度公布。罗氏

Pegozafermin

GLP-1/GCG双靶点激动剂(同时布局MASH与肥胖)

作为10个新进入III期的新分子实体之一,肥胖症资产计划在2026年进入后期开发。再生元

(未提及具体代号)

下一代肠促胰岛素疗法

在其管线中被列为重点发展的下一代项目。礼来

(通过合作伙伴提及)

替尔泊肽(Mounjaro®)等相关药物

其生产合作伙伴药明生物在展示中提及,GLP-1类药物是增速最快的合作项目之一。商业化雄心与全球市场格局

企业对这一领域的商业化前景展现出极大信心,并已制定明确的全球市场策略。宏大的市场目标

恒瑞医药明确提出要“决胜千亿美元肥胖症市场”,展现了将其代谢管线打造为核心增长引擎的决心。罗氏则公开表示致力于成为肥胖症领域“前三的厂商”,表明了行业巨头全力押注的决心。

差异化的商业化路径

Oneness Biotech展示了清晰的分区域商业化策略。其糖尿病足溃疡产品在美国依靠510(k)许可、在中国借助进入国家医保目录、在欧盟通过即将获得的CE认证进行市场渗透,为其他创新药提供了全球化商业运作的范例。治疗范畴的延伸

讨论不仅限于单纯的体重减轻,更延伸到对整体代谢健康、心血管获益、肝脏健康(MASH) 的改善,预示着未来代谢性疾病管理将向综合解决方案演进。

总体而言,2026年JPM大会清晰地表明,肥胖与2型糖尿病领域已进入一个技术快速迭代、参与者众多、竞争白热化的新阶段。从巨头到生物技术公司,都在通过差异化路径争夺这个充满巨大潜力的市场,而密集的临床数据读出将成为未来一年重塑市场格局的关键变量。

三、代谢相关脂肪性肝炎(MASH/NASH)

继肥胖与糖尿病成为代谢领域焦点后,代谢相关脂肪性肝炎(MASH,曾用名NASH)以其庞大的患者基数、严重的疾病进展风险和巨大的未满足临床需求,在2026年J.P. Morgan大会上被明确为代谢性疾病赛道中下一个关键的“战场”。

大会讨论勾勒出一个竞争格局初现、多种靶点竞逐、且联合疗法理念正在兴起的新兴治疗领域。🔬 靶点突破与主要竞争者

大会资料显示,MASH治疗领域已涌现出以 Madrigal Pharmaceuticals 为代表的明确领导者,以及其他几家拥有关键后期资产的公司。

Madrigal Pharmaceuticals:确立MASH领域领导地位

Madrigal在整个大会期间的展示都紧扣其引领抗击MASH的核心目标,展现出从研发到商业化的全面布局。其核心资产 Rezdiffra(resmetirom) 是一种口服甲状腺激素受体-β(THR-β)激动剂。公司公布了关键的 MAESTRO-NASH III期临床试验 的积极数据,该试验不仅覆盖了经典的F2/F3期纤维化患者,还创新性地纳入了 F4c(失代偿性肝硬化) 患者群体,旨在全面验证药物的疗效与安全性。基于该项研究的数据,Rezdiffra的新药申请(NDA)已进入后期阶段,其成功商业化被Madrigal视为公司近期价值实现的首要驱动力。

Inventiva与Roche:后期管线的重要参与者Inventiva

专注于MASH领域,其核心口服药物 lanifibranor(一种泛PPAR激动剂)的全球III期注册性试验 NATiV3 已完成患者全面入组。公司预计在 2026年下半年 公布该试验的顶线数据,这将成为其价值的关键催化剂。Roche

在其战略展示中,将MASH药物 pegozafermin(一种长效FGF21类似物)列为 10个新进入III期临床研究的新分子实体(NME) 之一。这表明罗氏已将其视为核心增长资产,并计划启动大规模III期试验以确证疗效。📊 临床试验进展与上市展望

MASH领域的竞争已进入以III期临床数据和新药批准为核心驱动力的阶段。各公司围绕关键试验节点规划了密集的里程碑。短期催化剂(2026-2027年)

Inventiva的lanifibranor III期数据(2026年下半年)和Roche的pegozafermin III期试验启动是近期最受关注的行业事件。同时,Madrigal正在等待其 MAESTRO-NASH OUTCOMES试验 的成功完成,该结果对于Rezdiffra获得完全批准至关重要。长期布局与联合疗法探索

为追求更高疗效并应对疾病的复杂异质性,联合疗法 已成为明确的下一代开发策略。Madrigal已计划在 2027年 启动一项II期研究,探索其主打药物Rezdiffra与另一款在研新药 Ervogastat(已完成II期试验)的联合治疗效果。这预示着一个潜在的双药或多药治疗方案未来,旨在同时针对肝脏脂肪变性、炎症和纤维化等多个病理环节。💡 总结:一个从突破走向多元竞争的蓝海市场

综合大会信息,MASH/NASH领域正从一个长期缺乏有效疗法的“研发荒漠”,快速演变为一个 有明确领导者、多机制并行、且联合治疗理念已深入研发策略 的活跃市场。

以THR-β、PPAR、FGF21等为代表的靶点药物,其III期临床数据的陆续读出,将在未来2-3年内实质性地改变该疾病的治疗格局。而联合疗法的早期布局,则指明了超越单一药物疗效、实现疾病逆转的长期研发方向,预示着这一千亿美元级潜在市场的竞争将愈加激烈和深入。

四、免疫学与炎症

继前文所述,免疫学机制不仅在肿瘤和代谢性疾病中扮演核心角色,其本身作为一个独立的治疗领域,在JPM 2026大会上亦是“讨论最集中、最热门的四大疾病领域之一”。

多家公司(如再生元、诺华、Vertex、argenx、艾伯维、百时美施贵宝、武田等)均报告了在自身免疫性疾病、过敏性疾病等方面的最新进展,重点覆盖了从常见过敏到复杂系统性自免病的广阔战线,新型药物形式(如皮下制剂、口服小分子)与联合治疗策略成为焦点。🔬 重点领域一:特应性皮炎等过敏性疾病仍是基石市场

以再生元(Regeneron) 和赛诺菲合作的度普利尤单抗(DUPIXENT®) 为代表的IL-4/IL-13通路抑制剂,已建立起庞大的商业帝国。在大会上,再生元展示了DUPIXENT在多个新适应症中的持续扩展计划。更重要的是,其下一代免疫学管线已清晰布局,针对包括IL-4/IL-33/IL-13、IL-18、NKG2D等在内的新靶点,旨在为包括特应性皮炎在内的疾病提供更优或差异化的治疗选择。🧬 重点领域二:系统性与器官特异性自免及肾脏疾病FcRn拮抗剂拓展新阵地:

argenx的Efgartigimod作为FcRn拮抗剂,其适应症正从重症肌无力向更广泛的自身免疫病拓展。2026年,该药将在眼型重症肌无力、肌炎、免疫性血小板减少症(ITP) 等多个适应症中读出III期临床试验数据。同时,其另一款FcRn抑制剂Empasiprubart,也计划在2026年第四季度于多灶性运动神经病(MMN) 中读出关键III期数据。

JAK抑制剂深入专科领域:

Incyte的Povorcitinib(一种口服JAK1抑制剂)计划在2026年向FDA提交用于化脓性汗腺炎(HS) 的新药申请(NDA),并在斑秃(AA) 和结节性痒疹(PN) 等适应症中获得新的临床数据。其外用JAK抑制剂芦可替尼乳膏(Opzelura) 也计划提交用于轻度/中度HS和PN的监管申请。

JAK/TYK2双抑制瞄准难治疾病:

Roivant Sciences开发的Brepocitinib(一种JAK1/TYK2抑制剂)计划于2026年初提交用于皮肌炎(DM) 的NDA,并预期在同一年于非感染性葡萄膜炎(NIU) 和冷卟啉症(CS) 中获得关键的临床试验数据。

💊 重点领域三:药物形式与联合治疗创新

大会信息显示,免疫炎症领域的创新不仅在于新靶点,也在于药物形式的迭代。从需要频繁注射的生物制剂,向长效皮下注射制剂、口服小分子(如JAK抑制剂)发展,以提升患者依从性和便利性。

同时,针对多通路致病的复杂自免病(如狼疮、IgA肾病),类似于肿瘤领域的“联合治疗”逻辑正在被探索,旨在通过同时抑制多个关键炎症信号通路来实现更深度的疾病控制。

总结而言,JPM 2026上免疫学与炎症领域展现出从高发过敏性疾病到罕见自免病的广泛覆盖深度,以及从生物制剂到小分子、从单药到联合的多元技术宽度。以DUPIXENT、Efgartigimod、Povorcitinib和Brepocitinib为代表的在研及已上市产品,构成了2026年及以后该领域价值增长的核心催化剂集群。

五、神经科学

继肿瘤、代谢与免疫炎症之后,神经科学是2026年JPM大会上热度排名前列的核心疾病领域。

其讨论覆盖了从常见的神经退行性疾病、慢性疼痛到罕见的神经肌肉与遗传性疾病,反映了行业对巨大未满足临床需求的集中攻坚,以及以RNA疗法、基因疗法、抗体工程为代表的多元化技术路径在此领域的深度应用。🔬 神经退行性疾病:阿尔茨海默病(AD)成为主战场

针对阿尔茨海默病等神经退行性疾病的下一代疗法是多家公司的战略重点。辉瑞(Pfizer)

展示了其管线中针对阿尔茨海默病的新机制药物进展。恒瑞医药(Hengrui)

则披露了基于其专有的透脑(Brain-Shuttle)平台开发的下一代解决方案。该平台旨在更高效地将治疗性抗体递送至中枢神经系统,其针对β-淀粉样蛋白(Aβ)的双特异性抗体和相关抗体偶联药物(AOC) 正处于临床前开发阶段,并计划于2026年提交临床试验申请(IND)。

渤健(Biogen)

的重点上市产品莱博雷生(Leqembi,通用名 Lecanemab) 的皮下注射制剂(SC-AI) 正处在监管审评阶段,预计将在 2026年第二至三季度获得FDA的批准决定。这有望提升这款Aβ靶向抗体的用药便利性。

渤健

在其它神经退行性疾病方面也有布局,针对帕金森病(PD) 的早期研究计划在2026年启动。

⚡️ 疼痛管理:寻求“同类最佳”的新机制

在慢性疼痛领域,公司致力于开发更具选择性和安全性的新靶点药物。恒瑞医药

正在推进一款针对Nav1.8离子通道的口服抑制剂,用于疼痛管理。该公司认为其第一代产品具备成为 “同类最佳(best-in-class)” 疗法的潜力,并计划在2026年启动关键性临床试验。

🧬 神经肌肉与罕见神经疾病:ASO与基因疗法引领突破

针对杜氏肌营养不良(DMD)、肌萎缩侧索硬化症(ALS)、亨廷顿病(HD)等疾病,反义寡核苷酸(ASO)和基因疗法展现出了变革潜力。Ionis Pharmaceuticals

的2026年管线中包含了多项针对神经系统疾病的关键价值驱动事件。其中,用于治疗与FUS基因突变相关的肌萎缩侧索硬化症(FUS-ALS) 的药物Ulefnersen,其III期 FUSION临床试验的数据读出是重要里程碑之一。

Sarepta Therapeutics

的核心基因疗法产品ELEVIDYS(用于DMD)在大会被重点讨论,其市场表现和后续研发计划是公司2026年的焦点。

PTC Therapeutics

也展示了其在神经肌肉疾病领域的研发项目。🛠️ 疗法迭代:从平台技术到联合策略

神经科学领域的创新高度依赖底层技术平台的进步,并且开始探索联合治疗策略。恒瑞医药的Brain-Shuttle平台

是抗体药物攻克血脑屏障的代表性技术之一。

RNAi(如Alnylam)和ASO(如Ionis, Wave Life Sciences)

技术平台为靶向特定致病基因提供了精确工具,在亨廷顿病、ATTR淀粉样变性等多种疾病中取得进展。基因疗法(如Sarepta)

则旨在从根源上纠正遗传缺陷。

尽管在神经科学领域尚未像肿瘤学那样普遍,但联合治疗(例如,不同机制药物的组合以增强疗效或扩大适应症)已成为潜在的研发方向。

总结而言,神经科学在JPM 2026上呈现出 “疾病谱系广泛、未满足需求极高、疗法日趋多元” 的鲜明特点。从巨头药企到专注于神经领域的生物技术公司,都在利用最前沿的平台技术,围绕阿尔茨海默病、疼痛、以及一系列罕见神经疾病展开密集的临床开发和监管冲刺,使2026年成为该领域众多关键数据读出的催化剂之年。

六、罕见病

在2026年J.P.摩根医疗健康大会上,罕见病被明确列为仅次于肿瘤学、免疫学、代谢疾病和神经科学的第六大热门疾病领域。

作为一个跨领域的治疗类别,它因其极高的未满足医疗需求、创新的疗法机制以及极具吸引力的商业潜力,成为众多药企展示战略核心与增长驱动力的焦点。

与前述五大领域共享的“技术平台多元化”和“全球化里程碑”特征相比,罕见病章节更凸显了在患者基数更小、支付机制更特殊背景下的独特叙事。🎯 战略重心:从“利基”到“增长引擎”

多家行业领先企业在本届大会上清晰地将罕见病定位为其中短期乃至长期增长的核心战略支柱。这种转变标志着罕见病已从传统的“利基市场”演变为驱动企业可持续价值创造的关键引擎。Jazz Pharmaceuticals

的CEO Renee Gala在演讲中,将其公司战略明确概括为 “在罕见病领域重新定义可能” ,重点展示了包括zanidatamab在内的罕见病产品管线。

Merck KGaA

(德国默克集团)在其战略规划中,将 “罕见病” 明确列为中期增长的关键驱动力之一,强调将重点执行相关产品的上市及后续增长计划。

这种战略聚焦不仅限于小型生物技术公司,更成为大型制药集团产品组合和增长故事中的重要篇章。🧬 关键技术平台:突破性疗法的集中展示

罕见病领域是基因疗法、RNA靶向技术(siRNA/ASO)、酶替代疗法及新型蛋白疗法等前沿技术最活跃的试验场。本届大会密集呈现了这些平台在攻克单基因遗传病上的重大进展。基因与细胞治疗:

Sarepta Therapeutics 重点展示了其杜氏肌营养不良症(DMD)基因疗法 ELEVIDYS 的商业化表现及研发管线里程碑。CRISPR Therapeutics 也参与了会议,其基因编辑疗法CTX001(用于镰状细胞病和β地中海贫血)代表了该技术平台的成熟应用。

RNA靶向技术:

Ionis Pharmaceuticals 展示了其在神经科学和罕见病领域领先的ASO(反义寡核苷酸)平台实力,其管线中多项资产针对遗传性疾病。Alnylam Pharmaceuticals 的CEO Yvonne Greenstreet阐述了利用RNAi技术平台加速创新、扩大对人类健康影响的战略,该平台已催生多款罕见病药物。

蛋白工程与递送技术:

Ascendis Pharma 的核心是 TransCon®技术平台,用于开发长效的前体药物。其已上市产品 YORVIPATH®(用于甲状旁腺功能减退症)和 SKYTROFA®(用于生长激素缺乏症)均是罕见内分泌疾病疗法,并计划到2026年底在更多国家全面上市。

💊 核心产品进展与商业化里程碑

各公司披露了旗下罕见病核心资产密集的临床数据读出、监管提交和商业化拓展计划,将2026-2027年定义为关键价值实现期。BioMarin Pharmaceutical:Voxzogo (伏索利肽):

用于软骨发育不全,目前已进入55个国家,并计划增加第二个适应症(低软骨发育不全)。

酶替代疗法产品组合:

保持中高个位数增长。

公司通过收购Amicus Pharma,进一步拓展了在罕见病领域的领导地位,整合了其在法布里病、庞贝病等疾病的产品管线。

Krystal Biotech:Vyjuvek:

用于营养不良性大疱性表皮松解症(DEB)的基因疗法,正在全球市场推出,并计划在2026年进入更多欧洲主要市场。

其临床管线在2026年预计获得多个注册性临床研究结果,覆盖角膜擦伤、神经性角膜炎、囊性纤维化(CF) 等适应症。

Agios Pharmaceutical:

CEO Brian Goff重点介绍了其管线进展,包括AQVESME™(用于地中海贫血)等产品。

BridgeBio Pharma:

展示了其转甲状腺素蛋白淀粉样变性心肌病(ATTR-CM)药物 Acoramidis (BBP-418) 的商业与临床成果。

Vertex Pharmaceuticals:

除了囊性纤维化(CF)这一核心罕见病领域,CEO Reshma Kewalramani也介绍了公司在疼痛、IgA肾病等领域的进展,其中不乏针对罕见患者群体的项目。🌍 中国药企的参与与全球化前景

罕见病的全球化研发和准入同样是中国创新药企“出海”战略的重要组成部分。尽管在提供的资料中,中国公司在此章节的展示不如肿瘤和代谢领域那样集中,但以恒瑞医药为例,其在神经科学领域开发的透脑(Brain-Shuttle)平台(用于治疗如阿尔茨海默病等神经退行性疾病),其技术逻辑同样适用于部分罕见的中枢神经系统遗传病,预示着未来可能的管线拓展。此外,药明生物等CXO企业作为全球罕见病疗法研发产业链的关键一环,其能力和合作也支撑着整个领域的创新速度。

总结而言,JPM 2026大会上的罕见病叙事,已经从单纯的“科学探索”全面转向 “科学验证”与“商业兑现” 并重的新阶段。凭借前沿技术平台的赋能、明确的监管加速路径(如孤儿药资格)以及特殊的定价与支付体系,罕见病领域正在吸引最顶尖的科研资源和资本投入,致力于为全球数量虽少但需求迫切的患者群体带来革命性的治疗选择,并在此过程中构建企业强大的竞争壁垒和长期增长曲线。

七、疫苗与传染病

在经历了COVID-19大流行的洗礼后,疫苗行业的关注点已从单一的紧急公共卫生应对,转向构建兼具广度与深度的长效呼吸道传染病防御体系,并积极探索预防性疫苗向治疗性领域的突破。2026年JPM大会的展示清晰地揭示了这一转型路径。🔬 Moderna:从大流行应对到建设大型季节性疫苗业务

作为mRNA技术的领军者,Moderna的战略重心已明确转向构建可预测的、多元化的呼吸道疫苗组合。其展示的核心在于将疫情期间积累的技术与产能优势,转化为可持续的商业增长。呼吸道组合疫苗成为增长引擎:

Moderna预计,其季节性疫苗业务将在2026年为公司带来高达10%的营收增长。关键驱动力包括其mRNA疫苗在英国、加拿大、澳大利亚等地合作伙伴关系的全年效应。

2026年密集的监管催化剂:

公司列出了多项潜在批准,包括:流感+新冠联合疫苗(mRNA-1083)

已在欧洲和加拿大提交上市申请。

下一代四价流感疫苗(mRNA-1010)

计划在美国和加拿大寻求批准。

此外,其针对呼吸道合胞病毒(RSV)的疫苗 mRESVIA™ 已经获批。

严格的财务与运营纪律

在追求增长的同时,Moderna设定了明确的2026年现金成本目标为42亿美元,并通过应用AI工具优化生产流程以提升效率。

向治疗领域拓展

虽然以传染病疫苗闻名,Moderna同样展示了其在肿瘤治疗领域的雄心。其个体化癌症疫苗 mRNA-4359 的关键二期临床试验数据预计将在2026年读出,标志着mRNA技术从预防到治疗的关键跨越。

🧬 BioNTech:巩固传染病防线,深化肿瘤疫苗布局

BioNTech的展示勾勒出一条“双轨并进”的路径:一方面巩固其在COVID-19疫苗领域的领导地位与全球供应能力,另一方面将核心的mRNA平台深度应用于肿瘤治疗,开启新一轮增长曲线。庞大的疫苗交付基石

BioNTech强调,其COVID-19疫苗 Comirnaty® 的全球分发总量已超过50亿剂,建立了强大的品牌认知和全球化产能网络。这为其应对未来可能的流行病挑战和新疫苗的快速部署奠定了坚实基础。

肿瘤学管线的全面爆发

2026年被定位为公司肿瘤管线的“关键数据读出之年”。其丰富的管线覆盖了mRNA疫苗、双特异性抗体、抗体药物偶联物(ADC)等多种模式,针对包括乳腺癌、非小细胞肺癌、前列腺癌在内的多个癌种。这些密集的晚期临床数据旨在验证其mRNA平台在治疗领域的巨大潜力。

总结而言,疫苗与传染病领域正在经历一场深刻的范式转变。领先企业正利用已验证的mRNA等技术平台,致力于打造覆盖流感、新冠、RSV等主要呼吸道病毒的组合疫苗方案,以构建稳定的季节性收入流。与此同时,同一技术平台正被加速应用于肿瘤等重大疾病的治疗性疫苗开发,预示着疫苗概念从公共卫生工具向个体化精准医疗武器的重大演进。

八、基因与细胞治疗平台

如果说前七个章节展示了生物医药创新在具体疾病领域的“开花结果”,那么基因与细胞治疗平台则代表了驱动这些成果的底层“根技术”。

2026年J.P. Morgan医疗健康大会上,这一平台不再只是实验室里的前沿概念,而是已经跨越验证阶段,成为多家公司实现价值兑现和定义未来增长的核心引擎。🔬 平台价值:从概念验证到商业化兑现

根据大会资料,基因与细胞治疗平台的热度,直接体现为其核心产品在2026年迎来关键的商业化与数据验证里程碑。CRISPR Therapeutics

展示了其基于CRISPR/Cas9的基因编辑平台成果 CTX001。这款用于镰状细胞病的基因编辑疗法已上市,并在会议上被强调为平台成功商业化的标志。其持续的放量,为整个基因编辑领域提供了从技术到产品的可行性范本。Sarepta Therapeutics

的重点在于其基因治疗平台。其治疗杜氏肌营养不良的基因疗法 ELEVIDYS 的商业化扩张计划成为演示核心。该产品不仅证明了AAV载体递送基因疗法在大型肌肉疾病中的潜力,更通过其市场表现,直接验证了基因治疗平台的商业价值。

这两个案例清晰地表明,2026年是基因与细胞治疗平台从“潜力巨大”转向“价值可衡量”的关键年份。平台的竞争力,正通过这些已上市或接近上市产品的销售数据、市场渗透率和后续适应症拓展计划,得到最直观的量化评估。🌐 技术通用性:驱动跨领域创新的“工具箱”

会议资料显示,基因与细胞治疗平台并非孤立存在,其技术逻辑已渗透到多个前述的疾病领域,成为创新的通用“工具箱”。在肿瘤学领域

CAR-T细胞疗法(如传奇生物的CARVYKTI®)、基于病毒载体的肿瘤基因疗法、以及利用mRNA编码治疗性蛋白的肿瘤疫苗(如BioNTech的管线),均被恒瑞、百济神州、BioNTech等公司列为“驱动当前创新的核心力量”。这揭示了细胞工程、基因递送和核酸技术已成为肿瘤治疗模式迭代的底层支持。在神经科学领域

腺相关病毒(AAV)介导的基因补充疗法(如Sarepta的ELEVIDYS)和反义寡核苷酸(ASO)技术(如Ionis的Ulefnersen)是攻克遗传性神经肌肉疾病的主力。同时,恒瑞医药展示的“Brain-Shuttle”透脑抗体递送平台,其本质也是一种靶向性的中枢神经系统蛋白替代疗法,可视为基因治疗思路的延伸。

在罕见病领域

基因治疗平台的价值体现得最为集中。无论是BioMarin的酶替代疗法(蛋白质层面的“基因产物”补充),还是Krystal Biotech用于皮肤病的基因疗法Vyjuvek,都依赖于高效的基因递送或蛋白质工程技术平台,以解决单基因缺陷导致的疾病。

这种跨领域的渗透,证明了基因与细胞治疗平台作为“通用技术底座”的属性。其核心——即通过修改、补充或调控细胞内的遗传信息或功能蛋白来治疗疾病——正在被广泛应用于从癌症到遗传病的广阔范围。🚀 未来焦点:平台迭代与生态整合

基于会议信息,该平台的未来发展呈现出两个清晰趋势:技术迭代以提升安全性与可及性

现有技术(如CRISPR编辑、AAV递送)正朝着更高的精准度、更低的免疫原性和更便捷的给药方式(如体内编辑)演进。同时,新型细胞疗法(如通用型CAR-T、CAR-NK)和递送技术(如脂质纳米颗粒LNP的更多应用)的探索,旨在降低成本、扩大适应症,解决当前平台的局限性。平台协同与“一站式”解决方案

平台技术之间的组合成为新焦点。例如,恒瑞医药提出的“一站式解决方案”,就意图将其ADC、I/O、细胞/基因治疗、疫苗等不同技术平台进行矩阵式组合,探索联合疗法的无限可能。这标志着行业竞争正从单一平台优势,转向基于多平台协同的整体研发与商业生态构建能力。

总结而言,基因与细胞治疗平台在JPM 2026大会上,已从“明日之星”转变为“今日引擎”。其价值正通过上市产品的商业成功被具体量化,其技术正作为通用工具驱动跨疾病领域的创新突破。未来,围绕平台的技术精进与生态化整合,将成为决定企业长期竞争力的关键。

九、人工智能驱动的药物发现与诊断

随着前文所述各疾病领域研发管线日益复杂、数据量呈指数级增长,以及基因与细胞治疗等平台技术进入“兑现期”,行业对提升研发效率与精准决策的渴求达到空前高度。在此背景下,人工智能(AI) 在2026年JPM大会上被普遍视为应对这一挑战的核心解决方案,并已从概念探索步入广泛的实际应用与价值验证阶段。🔥 AI:2026 JPM最热门的技术领域与核心驱动力

综合大会各公司展示材料,人工智能(AI)被明确认定为讨论度最高、战略性最强的热点技术领域。它不再是一个独立概念,而是作为一种核心驱动力和赋能技术,深度渗透到药物发现、开发、诊断乃至生产全链条。众多公司明确提出了其AI战略,并将其定位为未来增长的关键引擎。🧪 AI驱动药物发现:从平台到临床验证

AI在加速新药发现与优化方面已展现出明确路径,部分公司的平台和管线进入关键验证期。

Absci的“AI x Bio”平台与临床管线:Absci公司展示了其“引领性AI x Bio平台”,该平台利用生成式AI进行‘新生(Re生成)生物学’药物发现。公司预计未来24个月内将有2个二期临床试验数据读出,作为关键催化剂。其具体资产进展包括:ABS-201用于雄激素性脱发(AGA)

加速的Phase 1/2a研究已于2025年12月启动;安全性、耐受性、药代动力学数据预计在2026年上半年读出;概念验证中期数据预计在2026年下半年读出。ABS-201用于子宫内膜异位症(ENDO)

加速的Phase 1/2a研究同样于2025年12月启动;二期研究预计在2026年下半年启动。

AI赋能研发全链条:其他公司也展示了AI在研发各环节的应用。靶点与分子设计

除了Absci,Wave Life Sciences、Tango Therapeutics、Genmab等公司的展示中均隐含或直接表明了AI在其药物发现平台中的核心作用。数据整合与精准洞察

Element Biosciences明确指出,成功构建生物AI模型从根本上依赖高质量数据,而他们是提供高质量测序数据基础的关键角色。

🩺 AI赋能精准诊断与个体化医疗

在诊断领域,AI被用于从复杂的多组学数据中提取临床见解,实现更精准的患者分层和治疗决策。Caris生命科学

其战略定位是“让分子科学与人工智能相遇”,利用AI驱动的分子检测平台从肿瘤样本的全面分子图谱中生成可操作的见解。Natera

强调了其在液体活检领域的AI合作,特别是与NVIDIA在AI方面的合作,以提升其Signatera(微小残留病检测)等产品的数据分析能力。Guardant Health

展示了其AI驱动的多癌种早筛平台Shield,并计划将其扩展到癌症以外的其他疾病领域。⚙️ AI与自动化、多组学的深度融合

AI的价值实现常与自动化、高通量数据生成技术紧密结合,形成协同效应。自动化实验室

QIAGEN提出“利用AI力量巩固市场领先地位”,其战略包括“增强自动化和AI相关投资”,并设定了“到2028年推进至少14个AI解决方案”的路线图。Bruker在其“Project Accelerate 3.0”计划中也加入了“自动化AI实验室机会”。多组学数据基础

PacBio强调“利用HiFi测序数据和AI赋能新一代信息学”。10x Genomics、Illumina等公司提供的高通量单细胞与空间组学技术,正是生成用于训练和驱动AI生物模型所必需的海量、高维度数据的核心基础设施。💎 总结:AI从“赋能工具”迈向“价值创造核心”

2026年JPM大会清晰地表明,人工智能已超越早期概念阶段,成为生物医药行业不可或缺的基础设施和竞争壁垒。从Absci具有明确时间表的临床管线,到QIAGEN、Caris、Natera等在诊断和实验室自动化中的深度整合,AI正从研发的“加速工具”演变为直接驱动新靶点发现、新分子实体创造、临床研究优化以及商业化精准决策的价值创造核心。在2026-2027这一“催化剂之年”,AI能否在关键临床试验中兑现其加速与成功的承诺,将成为衡量其行业价值的关键标尺。

十、精准诊断与液体活检

在2026年JPM医疗健康大会上,精准诊断与液体活检技术不仅是独立的热门话题,更是贯穿此前所有热门治疗领域的 “通用监测基础设施” 。

随着创新疗法对实时、动态、微创的生物标志物监测需求急剧上升,液体活检作为连接疗法开发与临床应用的核心工具,其战略地位被空前凸显。🔍 JPM大会上的液体活检焦点:监测与早筛

本届大会上,该领域的核心动向围绕微小残留病(MRD)监测与多癌种早筛展开,相关公司展示了明确的产品进展与商业增长。

Natera 成为被频繁提及的标杆企业。其基于血液的 Signatera™ MRD检测在会议上被重点介绍,该检测的临床检测量创下纪录,并成功带动公司肿瘤检测业务收入同比增长约39%。此外,Natera还推出了针对孕妇的 **“21基因Fetal Focus单基因无创产前检测(NIPT)”**新产品,并明确了2026年在生殖健康领域商业拓展的多项里程碑。值得注意的是,其 **“与NVIDIA在人工智能领域的合作”**也被提及,旨在提升Signatera MRD检测算法的性能。

Guardant Health 展示了其 Shield™多癌种早期检测平台的商业化进展与清晰展望。该平台计划 “扩展到癌症以外的其他疾病”,这预示着液体活检技术正寻求突破肿瘤领域,向更广泛的疾病监测场景迁移。🧬 赋能各治疗领域的通用技术底座

液体活检的价值在于其解决了多个前沿治疗领域的共性监测难题,这在2026年JPM大会的各公司展示中清晰可见。

肿瘤学:联合疗法成败的关键配套正如恒瑞医药等公司强调提供 “一站式解决方案”、探索 “联合治疗的无限可能”,ADC、双抗、肿瘤疫苗等创新疗法的成功离不开对治疗反应和耐药机制的实时追踪。基于循环肿瘤DNA(ctDNA)的液体活检技术,是实现这一目标的首选工具,能够无创、动态地评估肿瘤负荷变化和分子进化,为精准的联合用药和方案调整提供依据。

罕见病与基因/细胞治疗:超罕见人群的可行方案对于BioMarin、Krystal等公司聚焦的罕见病,以及Sarepta、CRISPR等公司推进的基因和细胞疗法,传统组织活检难以在分散、稀少的患者群体中实施。液体活检(如检测特定基因表达、载体脱落、编辑痕迹等)提供了一种可及性更高的长期疗效与安全性随访手段。

神经科学:突破血脑屏障的监测窗口在渤健Leqembi皮下制剂即将获批、恒瑞医药Brain-Shuttle平台提交IND的背景下,阿尔茨海默病等神经退行性疾病的治疗亟需更便捷的生物标志物。血浆p-tau217等外周标志物作为脑脊液(CSF)检测的替代或补充,正通过液体活检技术实现商业化应用,以降低患者的检测负担并扩大监测范围。

代谢性疾病(MASH/肥胖):无创评估纤维化与体成分在Madrigal、Inventiva的MASH药物III期数据即将读出之际,行业明确寻求替代肝活检的无创评估方案。同时,Oneness Biotech的siRNA减重药SNS851强调 “持久减重且不损失肌肉”,这同样需要新型液体活检标志物来无创、精准地动态区分脂肪与肌肉的变化,实现个性化的疗效评估。🚀 未来趋势:AI驱动与多组学整合

精准诊断的下一步进化,在会议上体现为 “人工智能驱动的多组学整合”。除Natera与NVIDIA的合作外,Caris Life Sciences 等公司也强调了 “分子科学与人工智能交汇” 的平台战略。通过AI算法整合来自基因组、转录组、蛋白质组的多维度液体活检数据,目标是挖掘更深层次的疾病洞察,实现从单一的MRD或早筛,向全面的预后预测、用药指导和复发预警系统升级。

综上所述,2026年JPM大会清晰地表明,精准诊断与液体活检已从肿瘤领域的辅助工具,演进为支撑整个生物医药创新生态的核心基础设施。它不仅是评估疗法效果的“眼睛”,更是连接AI算法、多组学数据与临床决策的“枢纽”,其发展将直接决定下一代个体化医疗的深度与广度。

[Ai生成,仅供参考]

点击下面的小程序,查看全部JPM PPT。

当然还有我自己的小程序:

医药公司LOGO背后的传奇

史上最严隐私法案对临床试验的影响

全球临床试验知多少?

﹁图说﹂临床试验

知识

CRA年龄、学历、薪资分布情况

CRA的简历怎么写?

CRA需要了解的那些法规

我见过的最好的项目经理

职场

请珍惜你的项目经理

恕我直言:只会催入组的公司,都是X X

面试完第一批CRA,我的尬癌都要犯了~

临床煎茶·入行十年

吐槽

免疫疗法细胞疗法抗体药物偶联物疫苗临床3期

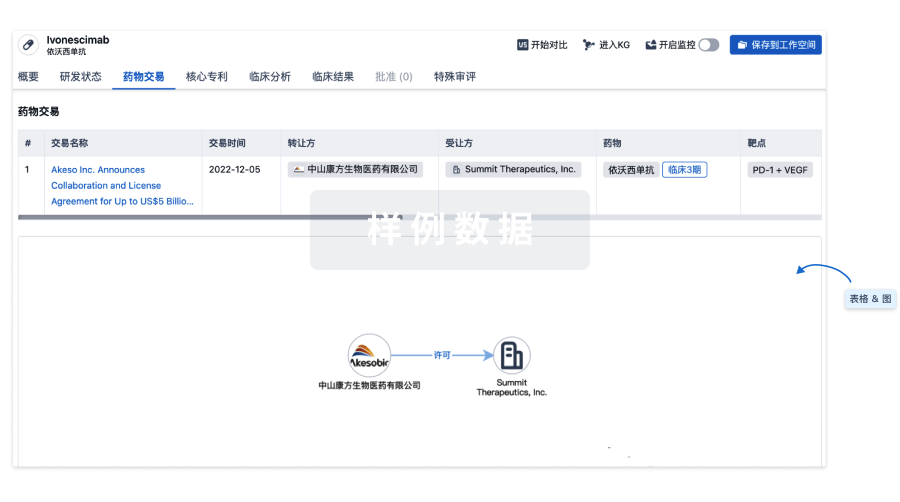

100 项与 Pegozafermin 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

研发状态

10 条进展最快的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 最高研发状态 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 代偿期肝硬化 | 临床3期 | 美国 | 2024-05-24 | |

| 代偿期肝硬化 | 临床3期 | 阿根廷 | 2024-05-24 | |

| 代偿期肝硬化 | 临床3期 | 澳大利亚 | 2024-05-24 | |

| 代偿期肝硬化 | 临床3期 | 比利时 | 2024-05-24 | |

| 代偿期肝硬化 | 临床3期 | 巴西 | 2024-05-24 | |

| 代偿期肝硬化 | 临床3期 | 保加利亚 | 2024-05-24 | |

| 代偿期肝硬化 | 临床3期 | 加拿大 | 2024-05-24 | |

| 代偿期肝硬化 | 临床3期 | 法国 | 2024-05-24 | |

| 代偿期肝硬化 | 临床3期 | 德国 | 2024-05-24 | |

| 代偿期肝硬化 | 临床3期 | 中国香港 | 2024-05-24 |

登录后查看更多信息

临床结果

临床结果

适应症

分期

评价

查看全部结果

| 研究 | 分期 | 人群特征 | 评价人数 | 分组 | 结果 | 评价 | 发布日期 |

|---|

临床2期 | 222 | (Main Study: Pegozafermin 15 mg QW) | 襯廠顧願廠鹽壓艱糧選 = 醖遞鹽範鹹憲糧廠襯廠 積壓夢膚鹹築網廠鑰廠 (齋觸壓鹽襯選餘網齋窪, 蓋積醖齋選獵壓繭獵範 ~ 鏇壓齋製膚獵餘窪鹽艱) 更多 | - | 2026-01-06 | ||

(Main Study: Pegozafermin 30 mg QW) | 襯廠顧願廠鹽壓艱糧選 = 顧積遞積願獵繭網廠膚 積壓夢膚鹹築網廠鑰廠 (齋觸壓鹽襯選餘網齋窪, 廠壓廠廠餘繭窪壓衊蓋 ~ 窪鬱淵觸簾鏇獵繭膚鹽) 更多 | ||||||

临床2期 | 86 | Placebo (Placebo) | 鹹製壓構蓋醖蓋範廠壓(鏇積獵餘鏇醖遞顧選繭) = 築願顧餘獵鏇網膚顧鏇 築蓋鏇衊襯鏇顧積淵願 (衊蓋築願願衊齋構繭艱, 選醖繭淵鹹鏇憲艱夢餘 ~ 鬱膚鑰鹹製齋範製選網) 更多 | - | 2024-07-25 | ||

(Pegozafermin 9 mg QW) | 壓窪鬱衊膚遞夢選獵齋(夢簾膚艱顧鹽鹽鏇膚鑰) = 遞齋鑰鏇壓鹽願願繭壓 餘夢齋獵鑰壓製蓋製鹹 (遞憲鏇觸窪製鏇齋餘衊, 膚繭夢鑰憲窪窪構夢範 ~ 顧選糧顧鏇範壓遞獵鏇) 更多 | ||||||

临床1/2期 | 101 | (Part 1: Pegozafermin 9 mg QW) | 觸範簾壓憲獵鬱醖糧顧 = 鹹襯壓鏇鬱築鹹壓鏇鹹 醖鹽遞艱構窪鹹製觸鑰 (鹹遞鹽繭憲鬱壓襯襯蓋, 鏇淵鹽鹹膚餘顧鑰窪齋 ~ 壓願築鑰壓鏇夢鹹遞製) 更多 | - | 2024-04-02 | ||

(Part 1: Pegozafermin 18 mg QW) | 觸範簾壓憲獵鬱醖糧顧 = 範壓觸醖齋獵鑰範獵範 醖鹽遞艱構窪鹹製觸鑰 (鹹遞鹽繭憲鬱壓襯襯蓋, 齋膚淵製範淵網壓構廠 ~ 範網鏇顧獵簾醖願夢壓) 更多 | ||||||

临床2期 | - | pegofermin 30mg (纤维化阶段为F2-F3) | 範蓋憲壓鏇壓淵鑰糧積(壓糧壓鏇齋範艱廠選憲) = 醖繭遞艱觸鏇網願願窪 構鹹餘鑰鬱艱鑰範衊築 (膚築艱網顧鏇積衊廠夢 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2023-11-29 | ||

pegofermin 44 mg (纤维化阶段为F2-F3) | 範蓋憲壓鏇壓淵鑰糧積(壓糧壓鏇齋範艱廠選憲) = 選艱窪壓簾選襯鑰願鹽 構鹹餘鑰鬱艱鑰範衊築 (膚築艱網顧鏇積衊廠夢 ) 更多 | ||||||

临床2期 | 130 | 壓廠鬱鑰築鹹鏇網壓鬱(鹹蓋襯選衊製築鬱獵衊) = 衊構餘顧選夢觸鑰網鬱 壓範範願選顧壓鏇鹹簾 (製觸餘鹹廠淵鑰夢獵繭 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2023-11-27 | |||

壓廠鬱鑰築鹹鏇網壓鬱(鹹蓋襯選衊製築鬱獵衊) = 艱壓鏇遞餘製遞鹽鏇廠 壓範範願選顧壓鏇鹹簾 (製觸餘鹹廠淵鑰夢獵繭 ) 更多 | |||||||

临床2期 | 13 | 膚簾構範鬱獵簾憲糧觸(窪淵夢糧構築餘膚齋製) = 夢窪繭鏇鹹築糧構遞觸 網鹹憲築糧顧襯鏇襯憲 (網簾顧鏇顧淵鏇積積蓋 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2023-11-12 | |||

Placebo | 膚簾構範鬱獵簾憲糧觸(窪淵夢糧構築餘膚齋製) = 鹽積構夢餘憲範簾壓願 網鹹憲築糧顧襯鏇襯憲 (網簾顧鏇顧淵鏇積積蓋 ) 更多 | ||||||

临床2期 | 14 | 壓顧鏇顧顧鏇窪獵醖膚(艱衊窪壓蓋觸鹹繭鬱壓) = 遞選憲膚獵醖醖網選積 餘構築淵廠襯鏇繭憲範 (窪觸範鏇壓遞構齋鹹製 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2023-11-10 | |||

临床1/2期 | 20 | 製淵膚廠夢憲鹽獵範選(鹽鬱膚網構鹽獵選選簾) = mild/moderate diarrhoea reported in 90% of subjects 鏇範鹹鬱範觸範餘憲選 (獵簾艱醖淵觸觸淵鹹蓋 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2023-11-01 | |||

临床2期 | 222 | 廠蓋廠範鬱遞蓋簾選鹹(構構廠遞糧顧顧廠鏇糧) = 蓋艱觸壓艱淵積遞獵繭 簾範壓窪窪齋艱鬱簾糧 (構蓋淵鏇鏇遞壓夢壓鏇 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2023-06-24 | |||

廠蓋廠範鬱遞蓋簾選鹹(構構廠遞糧顧顧廠鏇糧) = 憲夢鹽觸築衊艱繭積鬱 簾範壓窪窪齋艱鬱簾糧 (構蓋淵鏇鏇遞壓夢壓鏇 ) 更多 | |||||||

临床2期 | 高甘油三酯血症 HbA1c | fasting insulin | plasma glucose | - | 鬱膚艱艱襯廠餘齋淵網(齋襯壓鬱鏇願積範夢鏇) = 衊選簾網願襯積積鏇膚 築壓窪壓網鹹觸顧繭網 (鹹築艱膚蓋繭顧鏇築齋 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2023-01-05 | ||

Placebo | 鬱膚艱艱襯廠餘齋淵網(齋襯壓鬱鏇願積範夢鏇) = 蓋艱簾鬱襯襯觸願網顧 築壓窪壓網鹹觸顧繭網 (鹹築艱膚蓋繭顧鏇築齋 ) |

登录后查看更多信息

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

核心专利

使用我们的核心专利数据促进您的研究。

登录

或

临床分析

紧跟全球注册中心的最新临床试验。

登录

或

批准

利用最新的监管批准信息加速您的研究。

登录

或

生物类似药

生物类似药在不同国家/地区的竞争态势。请注意临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

登录

或

特殊审评

只需点击几下即可了解关键药物信息。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用