预约演示

更新于:2025-05-07

P2X3 receptor x P2RX2

更新于:2025-05-07

基本信息

关联

6

项与 P2X3 receptor x P2RX2 相关的药物作用机制 P2RX2 antagonists [+1] |

非在研适应症 |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期1800-01-20 |

作用机制 P2RX2 antagonists [+1] |

在研机构 |

原研机构 |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期1800-01-20 |

作用机制 P2RX2 antagonists [+1] |

非在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段临床前 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期1800-01-20 |

1

项与 P2X3 receptor x P2RX2 相关的临床试验NCT03116750

Post-Market Clinical Follow-up Study with the ASPIREX®S Endovascular System to Assess the Safety and Effectiveness in the Treatment of DVT Patients and Special Patient Groups

The ASPIREX®S Endovascular System is a rotating and aspirating catheter system. It is intended to be used for the percutaneous transluminal removal of fresh thrombotic or thromboembolic material from native blood vessels (or vessels fitted with stents, stent grafts or native or artificial bypasses) outside the cardiopulmonary, coronary and cerebral circulations.

CAPTUREX® , a catheter with a filter basket, is intended to be used for the filtering of emboli from blood vessels during potentially embolizing procedures on the patient.

ASPIREX®S and CAPTUREX® are CE-marked (Class III) medical devices. In this study the effectiveness and safety in the removal of thrombi in veins is assessed under real life setting.

CAPTUREX® , a catheter with a filter basket, is intended to be used for the filtering of emboli from blood vessels during potentially embolizing procedures on the patient.

ASPIREX®S and CAPTUREX® are CE-marked (Class III) medical devices. In this study the effectiveness and safety in the removal of thrombi in veins is assessed under real life setting.

开始日期2017-04-03 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 P2X3 receptor x P2RX2 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 P2X3 receptor x P2RX2 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 P2X3 receptor x P2RX2 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

191

项与 P2X3 receptor x P2RX2 相关的文献(医药)2025-01-10·ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science

Lipopolysaccharide-Neutralizing Peptide Modulates P2X7 Receptor-Mediated Interleukin-1β Release

Article

作者: Oldenburg, Johannes ; Dobbelstein, Ann-Kathrin ; Müller, Christa E. ; Weindl, Günther ; Klawonn, Anna ; Abdelrahman, Aliaa ; Engelhardt, Jonas ; Brandenburg, Klaus

2024-12-01·European Journal of Pharmacology

P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors inhibition produces a consistent analgesic efficacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies

Review

作者: Tejada, Miguel Ángel ; Marcos-Frutos, Daniel ; Huerta, Miguel Á ; Nava, Javier de la ; Huerta, Miguel Á. ; Roza, Carolina ; García-Ramos, Amador

2024-12-01·Acta Histochemica

Immunohistochemical distribution of cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) and type 2 (CB2) in the rat carotid body

Article

作者: Nakamuta, Nobuaki ; Yamamoto, Yoshio ; Saito, Hiroki ; Yokoyama, Takuya

7

项与 P2X3 receptor x P2RX2 相关的新闻(医药)2023-11-30

Chronic refractory cough is characterized by a coughing that lasts for more than eight weeks. Patients often experience incontinence and depression as well.

By the time GSK sealed the deal on Bellus Health in April, the U.K. pharma knew exactly what not to do with the phase 3 chronic cough program. The company had watched Merck & Co. struggle with a rival med called gefapixant, taking notes.

“When we were doing due diligence on acquiring camlipixant we looked at Merck’s program and it was pretty clear there was a number of things that we could build into our phase 3 program to reduce and actually avoid all the problems they’d had,” GSK’s Chief Commercial Officer Luke Miels told Fierce Biotech in an interview.

Now, after closing the $2 billion deal in June, GSK is showcasing the phase 3 camlipixant program and ready to replace Merck as the market leader. Two studies called CALM-1 and CALM-2 are currently enrolling now. While GSK has a long history in respiratory diseases, chronic cough is new territory—but somehow, still fits in nicely with GSK’s portfolio.

“Typically when you've got an R&D portfolio, you want to be entering some novel areas that you maybe have not had history there. You need to do that to evolve your portfolio,” Miels said. “I led the deal to acquire camlipixant. That was a core element.”

Gefapixant and camlipixant are both P2X3 antagonists that act on a peripheral nervous system receptor that triggers neuronal hypersensitization and is linked to the urge to cough. It’s believed that by preventing stimulation of P2X3, the therapies can reduce the severity and frequency of cough.

Merck is technically closer to market. However, gefapixant suffered a major setback earlier in November when an FDA advisory committee recommended against approval. In a 12-1 vote, the committee questioned whether the evidence clearly showed that the therapy made a difference in reducing cough frequency.

But being first, Merck also had to contend with the fact that the FDA had no regulatory precedent in the indication. The agency noted it had “limited experience with the endpoints used in this program.” So Merck, and now GSK, are treading new regulatory ground. The FDA has not officially ruled on gefapixant but is expected to do so by Dec. 27.

In explaining why GSK is “more confident” in camlipixant, Miels stressed that this is a real, chronic and extremely difficult condition. To bring Bellus under GSK’s wing, Miels himself dove into learning about what these patients deal with every day. The official name is chronic refractory cough and it's characterized by a person who is coughing for more than eight weeks.

“I got very engaged. When you read the disruption to these people’s lives—a typical patient is middle-aged, female, 50 to 65, coughing around 500 times a day,” Miels said. Around 50% have urinary incontinence and over 50% experience depression because of “societal aesthetics” and personal relationship challenges, which Miels said has worsened since COVID.

Gefapixant is approved under the brand name Lyfnua in the EU, Japan and Switzerland, leaving the world’s biggest markets wide open for GSK to play with. The Big Pharma identified several ways to prime the clinical program for success during due diligence.

First off, the program has a central adjudication that ensures patients in the trial are in fact experiencing chronic refractory cough. Then, the trial is enrolling only the most severe patients.

“Because as you get to lower cough rates, it can be a bit idiosyncratic as to what's the mechanism causing the cough, whereas patients with more severe high cough frequency typically are those that have cough generated via the neuropathic pathway, which is where camlipixant works,” Miels explained.

Third, the phase 3 study features a six-week placebo washout period, where patients are taken off any other cough treatments. “So you get a true placebo effect,” Miels said. Merck’s study did not have this protocol, he pointed out.

The phase 3 trial was designed in close coordination with the FDA given the uncertainty the agency had about the first effort to get a chronic cough medicine approved, Miels said.

“There are advantages in coming second and we’ve heavily built the phase 3 program based on what the agency valued,” Miels said.

GSK has also acted to ensure the software they use to count the coughs in the study is shored up, because this caused a major delay for Merck last year. The FDA rejected gefapixant in January 2022 due to the cough counting system used in a phase 3 test for the drug. While the measure was changed, the FDA still flagged issues with whether the submitted cough count data truly proved clinical meaningfulness.

“We've been able to learn what issues Merck had with the cough software because these people wear these devices that count the number of coughs for up to a year and they're constantly recording,” Miels said.

Another thing that’s different with GSK’s program is the molecule itself. Miels said that camlipixant is much more selective to the P2X3 target, meaning fewer side effects. As a result, GSK can use the maximum dose.

“If you look at Merck’s product gefapixant, it's more promiscuous and also is able to target a sibling receptor which is called P2X2. And the problem with P2X2 is it's present in the tastebuds,” Miels said.

This causes a metallic or bitter taste in the mouth, with some patients losing their sense of taste entirely, which was something the FDA flagged in its briefing documents for the advisory committee meeting. The side effect was experienced by 65% of subjects receiving 45 mg and prompted discontinuation of treatment for 14% of patients.

Another issue with taste disturbance is that it can unblind the study, as patients who experience this side effect know they have received the study drug. Camlipixant, meanwhile, has shown lower taste disturbance and no discontinuations.

Miels again noted that these patients are quite desperate for relief from their condition and doctors also want to have an option to offer that truly works. GSK looked at market research in its due diligence efforts that polled doctors on whether they are happy with the options available to them.

“Three percent cite 'yes' and 97% are very unhappy with the options that they have,” Miels said.

临床3期上市批准并购

2023-04-27

药物研发进展

1.君实生物 PCSK9 单抗两项适应症申报上市

4 月 26 日,据 CDE 官网显示,君实生物在研重组人源化抗 PCSK9 单克隆抗体注射液(JS002/昂戈瑞西单抗)申报上市(受理号:CXSS2300025)。据君实新闻稿,此次报上市有两项适应症,分别为:1)原发性高胆固醇血症(包括杂合子型家族性和非家族性)和混合型血脂异常。2)用于成人或 12 岁以上青少年的纯合子型家族性高胆固醇血症。根据《中国血脂管理指南(2023 年)》,近年来,中国人群的血脂水平及血脂异常患病率均呈上升趋势,成人血脂异常的总体患病率高达 35.6%。血脂异常,尤其是低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(LDL-C)水平升高是动脉粥样硬化性心血管疾病(ASCVD)的致病性危险因素,降低 LDL-C 水平可显著减少 ASCVD 的发病及死亡危险。HoFH 是由遗传因素(主要是 LDLR 基因突变)所致的家族性高胆固醇血症,是一种严重的可危及生命的罕见疾病。HoFH患者自出生就暴露在极高的 LDL-C 水平(通常>13 mmol/L)中, 大多在青少年时期即出现广泛的动脉硬化,若不积极治疗,大多数患者会在 30 岁之前死亡。由于 HoFH 患者 LDL-C 水平异常升高,现有的以他汀类药物为基 础的强化降脂治疗(包括降脂药物的联合应用)仍不能达到指南推荐的目标,无法满足 HoFH 患者的降脂治疗需求,HoFH 患者仍处于极高的心血管风险中。PCSK9 抑制剂作为强效降低 LDL-C 水平的新型降脂药物,已得到国内外血脂管理指南的推荐和临床医生的广泛认可。

2.优时比IL-17A/IL-17F单抗在华申报上市

4月26日,优时比(UCB)比吉利珠单抗注射液(bimekizumab)在华申报上市。bimekizumab是一种人源化单克隆IgG1抗体,旨在同时抑制白细胞介素 17A(IL-17A)和白细胞介素17F(IL-17F)这两种驱动炎症过程的关键细胞因子。这种独特的作用机制相比于其他IL-17A类药物可能有更好的疗效。bimekizumab于2021年8月在欧盟和英国获批用于适合系统治疗的成人中重度斑块状银屑病,2022年1月在日本获批,用于治疗对现有疗法响应不足的成人斑块状银屑病、泛发性脓疱型银屑病、红皮病型银屑病患者。2022年2月和3月又陆续在加拿大和澳大利亚获批。2022年12月7-11日,UCB在亚太风湿病学会联盟(APLAR)年会上公布了bimekizumab治疗放射学阴性axSpA和活动性强直性脊柱炎(AS)的两项III期研究(BE MOBILE 1&2)数据。其中,BE MOBILE 2研究的中国AS患者亚组(N=44)数据显示,患者的ASAS40应答比例为40.7%,显著高于安慰剂组(11.8%)。因此,UCB今日在中国申报的bimekizumab的适应症可能为AS。目前国内已有3款IL-17类生物制剂获批上市,不过均来自外企,分别是诺华的司库奇尤单抗、礼来的依奇珠单抗以及协和麒麟的布罗利尤单抗。除此之外,智翔金泰抗IL-17A单抗金泰赛立奇单抗注射液已于上月在国内递交上市申请。

3.渤健/Ionis 渐冻症疗法,获 FDA 加速批准

4 月 25 日,据 FDA 官网,渤健/Ionis 反义寡核苷酸(ASO)疗法 Tofersen(Qalsody)获 FDA 加速批准上市,用于治疗具有超氧化物歧化酶 1 突变的肌萎缩侧索硬化(SOD1-ALS)。这是首款针对ALS的基因靶向疗法。该适应症完全批准将取决于目前正在进行的tofersen在症状前SOD1-ALS患者中的III期ATLAS研究。Tofersen(BIIB067)是一款由 Biogen 和 Ionis 共同开发的靶向治疗成人 SOD1 基因突变型 ALS(SOD1-ALS)的反义寡核苷酸药物。Tofersen 能降解 SOD1 mRNA,以减少 SOD1 蛋白质的合成,防止有毒 SOD1 蛋白进一步积累,并允许自然清除机制去除现有的有毒SOD1 蛋白质。通过减少有毒 SOD1 蛋白质的数量,Tofersen 可以保护运动神经元完整性。此前披露的一项为期 6 个月的 Tofersen 用于成人 SOD1-ALS 患者的安全性和有效性的III 期临床 VALOR 试验结果显示,与安慰剂组相比,虽然 Tofersen 在 28 周内降低了脑脊液中的 SOD1 浓度和血浆中的 NfL 浓度,但在主要终点 ALSFRS-R 评分上并未产生显著性差别。基于该研究结果,对于该药能否顺利获批,彼时业内存在着一些争议。

4.创新口服HIF-PHI抑制剂在欧盟获批

4月25日,Akebia Therapeutics宣布,欧盟委员会(EC)已授予其口服HIF-PHI抑制剂Vafseo(vadadustat)上市许可,用于治疗接受慢性维持性透析的成人慢性肾脏疾病(CKD)相关的症状性贫血。该批准适用于所有27个欧盟成员国以及冰岛、挪威和列支敦士登。截至目前,vadadustat已在32个国家获得批准。Vadadustat是一种口服缺氧诱导因子脯氨酰羟化酶抑制剂(HIF-PHI),旨在模拟高海拔条件下身体对缺氧的生理效应。在高海拔情况下,身体对氧气稀缺的反应是提高缺氧诱导因子(HIF)的生成。HIF会调控铁元素的动员和促红细胞生成素(EPO)的产生来刺激血红细胞的生成,从而改善氧气运输。针对氧感知信号通路的研究已于2019年获得了诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。在针对接受透析成年患者的两项INNO2VATE研究中,vadadustat均达到了主要和关键的次要疗效终点,通过基线与主要评估期(第24至36周)和次要评估期(40至52周)之间血红蛋白(Hb)的平均变化来衡量,vadadustat对darbepoetin α(一种血红细胞刺激剂)无劣效性。Vadadustat还达到了INNO2VATE研究的主要安全终点,定义为在首次发生重大不良心血管事件时,vadadutat与对照药的非劣效性,这是两项INNO2VATE研究中全因死亡率、非致命性心肌梗死或非致命性中风的综合结果。Akebia公司首席执行官John P. Butler先生表示:“我们非常高兴欧盟委员会批准了Vafseo,这对Akebia来说是一个重要的里程碑,对数十万在透析中被诊断为CKD相关贫血的欧洲人来说更具影响力。”

5.康方启动 AK112 一线鳞状 NSCLC III 期临床

4 月 26 日,康方生物启动了一项其在研 PD1/VEGF 双抗 AK112 联合化疗对比 PD-1 抑制剂联合化疗一线治疗局部晚期或转移性鳞状非小细胞肺癌的 III 期临床研究(登记号:CTR20231272)。这是一项随机、双盲、对照、多中心的 III 期临床,旨在评估AK112 联合化疗(卡铂 + 紫杉醇)与替雷利珠单抗联合化疗在局部晚期或转移性鳞状非小细胞肺癌患者中的有效性和安全性。主要终点指标是独立影像评估委员会(IRRC)基于实体瘤疗效评价标准 1.1 版(RECIST v1.1)评估的无进展生存期(PFS),次要终点包括OS、ORR、DoR、DCR等。2022年12月6日,康方生物与Summit Therapeutics达成合作协议,后者获得康方生物PD-1/VEGF双抗AK112在美国、加拿大、欧洲、加拿大和日本的权益,Summit支付5亿美元预付款,以及最高50亿美元的总交易金额,包括开发、注册、商业化里程碑金额。Summit计划2023-2024年独自或与康方生物合作启动Ivonescimab的三期临床。勇于将临床最新方案作为阳性对照,开展头对头三期临床,是康方生物扎实创新的底气,也是整个中国生物医药行业进步的注脚。

6.Mophic小分子α4β7抑制剂:UC二期临床成功

4月25日,Morphic Therapeutics宣布小分子整合素α4β7抑制剂MORF-057治疗溃疡性结肠炎(UC)的二期临床EMERALD-1达到主要终点,次要终点的扩展检测也证明了临床意义的改善。分析显示,试验达成主要终点,患者的溃疡性结肠炎(UC)症状显著缓解。根据此积极结果,Morphic公司预计持续推进药品至2b期临床试验。在 EMERALD-1 中,接受 MORF-057 治疗的中度至重度溃疡性结肠炎患者的 RHI 评分显着降低,根据 mMCS 测量,临床缓解率为 25.7%。此外,MORF-057 耐受性普遍良好,未观察到安全信号。现在,值得期待的是Emerald-2实验,这是MORF-057的一项安慰剂对照的2b期试验,涉及280名患者,可能在未来几年产生数据。如果能取得良好的结果,相信MORF-057有机会成为下一个重磅炸弹。受此消息影响,Morphic Therapeutics股价涨7%,市值达到18.5亿美元。

7.GSK P2X3受体拮抗剂在国内申报临床

4月26日,CDE网站显示,GSK子公司Bellus Health的P2X3拮抗剂camlipixant(BLU-5937)在国内申报临床。该公司上周刚刚被GSK以20亿美元的总交易额收购。camlipixant是一种具有best-in-class潜力的高选择性P2X3受体拮抗剂,目前正在开展一线治疗难治性慢性咳嗽(RCC)患者的III期临床试验。RCC是指在对任何诱发咳嗽的基础疾病进行了最佳治疗或者无法识别诱发原因时,咳嗽症状持续超过8周。现有研究认为,咳嗽超敏反应综合征(对相对无害的刺激做出反应)导致的过度咳嗽是RCC的主要病理学机制。据估计,全球约2800万例慢性咳嗽患者,其中1000万例患者患有RCC长达一年。饱受RCC困扰的患者可能会导致抑郁症(53%)、尿失禁(~50%)、疼痛、肋骨骨折、社交回避和睡眠不足。gefapixant(默沙东/罗氏)是目前唯一一款获批用于治疗RCC的药物,不过仅在日本上市。研究表明,P2X3会提高气道感觉神经纤维的兴奋性,从而引发咳嗽超敏反应综合征。IIb期SOOTHE研究结果显示,通过选择性抑制P2X3受体,camlipixant(50mg和200mg,每日2次)可以显著降低RCC患者的每日咳嗽频率。此外,患者出现味觉障碍的概率(≤6.5%)相对较低,味觉障碍是P2X2/P2X3受体靶向药物常见的不良事件。

8.Provention Bio PRV-3279获批临床

4月26日,据CDE官网,Provention Bio PRV-3279获批临床,拟开展治疗系统性红斑狼疮的研究。PRV-3279 是一种人源化的双特异性抗体,靶向 B 细胞表面蛋白 CD32b 和 CD79b。此前研究显示,PRV-3279 可抑制 B 细胞功能和自身抗体的产生,但不引起B 细胞耗竭,耐受性良好。PRV-3279 具有治疗 B 细胞介导的自身免疫性疾病(如 SLE)和预防或降低生物治疗(如基因治疗)的免疫原性的潜力。系统性红斑狼疮可出现全身多脏器受累,以疾病复发、体内存在大量自身抗体为主要临床特点,如不及时治疗,会造成受累脏器的不可逆性损害,严重者可导致死亡。50~70%的系统性红斑狼疮患者病程中会出现肾脏损害,肾活检显示几乎所有系统性红斑狼疮均有肾脏病理学改变。狼疮性肾炎对系统性红斑狼疮预后影响甚大,肾功能衰竭是系统性红斑狼疮的主要死亡原因之一。

行业资讯

1.4.65亿美元!诺华获得3BP公司FAP靶向肽技术的全球权益

4月24日,专注癌症放射性疗法的3B Pharmaceuticals GmbH (3BP)公司宣布与诺华达成了一项授权合作协议。根据协议规定,诺华获得3BP公司的FAP靶向肽技术包括FAP-2286药物治疗和成像应用的全球开发和商业化独家许可权益,3BP保留了FAP靶向肽技术用于诊断目的的开发权益。3BP公司获得4000万美元的预付款,以及高达4.25亿美元的开发、商业化里程碑付款付款。靶向成纤维细胞活化蛋白(FAP)是针对多种恶性肿瘤的重要诊疗靶点。FAP-2286是3BP开发的一款放射性核素与FAP结合多肽的复合物,是一种肽受体放射性核素疗法(PTRT)。FAP-2286由两个功能元素组成:一个是与FAP结合的靶向肽,一个是可用于附着放射性同位素进行成像和治疗的位点,从而达到治疗的目的。如:68Ga与FAP-2286结合用于正电子发射断层成像;177Lu与FAP-2286偶联以用于治疗:抗肿瘤机制主要依靠177Lu(发射β粒子)靶向FAP阳性肿瘤细胞和CAF以及周围的FAP阴性肿瘤细胞,从而导致DNA损伤和细胞死亡。FAP-2286是第一个靶向FAP的肽受体放射性配体疗法(PT-RLT),目前正在进行1期临床试验(LuMIERE)。此前公布的177Lu-FAP-2286应用于其它疗法耐受的晚期转移性肿瘤患者的人体结果显示,177Lu-FAP-2286 PTRT可用于广谱肿瘤治疗,具有较好的耐受性和可接受的不良反应,并显示出放射性肽在肿瘤的长时间滞留。

2. 逾亿美元推进口服疗法进入3期关键试验

4月26日,Vedanta Biosciences公司宣布,已募集1.065亿美元,用于支持其主要在研药物VE303的关键阶段研发,用于预防复发性艰难梭菌感染(CDI),和用于溃疡性结肠炎的在研药物VE202的2期试验,以及其他研发活动。新闻稿指出,VE303为基于明确菌群的治疗候选药物,而VE303即将进行的试验将成为潜在首个此类药物的关键性3期试验。明确菌群指的是由细胞库生产的标准化组成产品,而非依赖成分不一致的供体粪便材料。微生物药物耐药性(Antimicrobial Resistance,AMR)是威胁人类健康未来的巨大危机,也是近年来世界卫生组织(WHO)工作所关注的焦点。在2022年的药明康德健康产业论坛中,全球抗菌药生态圈中最具影响力的机构和专家便针对此一危机作全面性的探讨,指出“没有一劳永逸的方法,也没有可以终结耐药的良方。我们需要持续稳定开发出新的抗生素,来解决不断出现的新需求。”而未来的关键之一,就是建立强大的新型抗菌药物管线。这次Vedanta所获得的大额融资亦显示产业界对AMR领域的逐渐重视。Vedanta公司正在开发一种潜在新类别的口服疗法,这些疗法基于从人类微生物组中分离出的细菌并从纯克隆细胞库中培养的明确菌群。公司的临床阶段产品线包括正在评估用于预防复发性CDI、炎性肠道疾病、食物过敏和肝脏疾病的候选药物。

临床结果优先审批引进/卖出融资

2023-04-25

关注并星标CPHI制药在线日前,葛兰素史克(GSK)和BELLUS Health宣布,双方已达成并购协议,GSK将以14.75美元/股的价格收购BELLUS,总交易额为20亿美元。通过此次收购,GSK将获得治疗慢性咳嗽的药物-- Camlipixant (BLU-5937)。 慢性咳嗽(RCC)是一种持续超过8周的咳嗽,病程可达数年甚至数十年。该疾病可发生于任何年龄,三分之二的患者是平均年龄在50-60岁之间的女性。这些病例中,患者要么对基础疾病(如哮喘或胃食管反流)的治疗无效,即难治性慢性咳嗽(RCC),要么尽管进行了彻底的评估,但仍没有明确的基础疾病,即不明原因的慢性咳嗽(UCC)。针对RCC或UCC,目前还没有批准的治疗方法,因此针对这两种患者的治疗手段非常有限,临床上存在着严重的未满足治疗需求。 随着对咳嗽机制研究的不断深入,以咳嗽通路为靶点的药物研发正在进行中。其中P2X3受体拮抗剂就是很有应用前景的药物。 什么是P2X3受体拮抗剂? P2X3受体是嘌呤类受体家族中的配体门控离子通道,其过度活化与感觉神经元的超敏化相关。研究发现,P2X3受体介导的迷走神经C纤维和Aδ纤维活化是诱发咳嗽和致敏的核心因素之一。P2X3受体作为连接三磷酸腺苷(ATP)与慢性致敏的主要底物,其持续刺激将导致机体长期的咳嗽高敏。因此,P2X3受体已成为慢性咳嗽治疗药物研究领域的一个重要靶点。 Camlipixant有望成为Best-In-Class 目前仅有默沙东引入的gefapixant在日本获批上市(FDA未批准),是市面上唯一一款获批上市的P2X3受体拮抗剂,于2022年1月和5月分别在日本和瑞士获批上市,用于治疗成人RCC。 2021年3月,默沙东向FDA递交了gefapixan的NDA申请,该NDA基于III期COUGH-1和COUGH-2临床试验的结果。在COUGH-1研究中,第12周时接受45mg每天2次gefapixant治疗的成年患者与安慰剂组患者相比,在24小时咳嗽频率方面相对于安慰剂减少了18.45%;在COUGH-2研究中,第24周时该数据相对于安慰剂组减少14.64%。gefapixant在平均每小时咳嗽频率上显著降低,且有统计学意义。 但是这一临床数据并未能打动FDA,主要原因在于gefapixant味觉方面的副作用。P2X3会参与非伤害性的感觉传导,且P2X2和P2X3比较接近,导致药物容易脱靶到P2X2,所以就P2X3靶点设计的药物,往往存在一种最常见的不良反应,就是味觉障碍。Gefapixant在一项III期临床试验中,45mg剂量组分别有58.0%和68.6%发生与味觉有关的不良反应,该剂量组有多达15%和20%的受试者中途因不良反应退出。 Camlipixant作为一种具有高度选择性的P2X3受体拮抗剂,临床数据显示,通过选择性抑制P2X3受体,camlipixant可以降低患有RCC患者的咳嗽频率,且产生味觉紊乱的药物相关不良事件的发生率相对较低。在BELLUS公布的一项IIb期临床试验中,一日两次50mg和200mg camlipixant的剂量达到主要终点,且所有剂量组的味觉相关不良事件率都较低(≤6.5%)。基于这些数据,BELLUS还启动了两项camlipixant的注册性III期临床试验(CALM-1和CALM-2),预计分别于2024年H2和2025年公布研究结果。 BELLUS此前预计将于2026年获得监管批准并推出camlipixant,若顺利获批,camlipixant将成为best-in-class的P2X3选择性拮抗剂。 其他P2X3受体拮抗剂研发进展 目前,全球在研的P2X3受体拮抗剂近20种,进展靠前的还有拜耳的BAY 1817080、盐野义的S-600918、朗来科技的QR052107B等。 部分P2X3受体拮抗剂研究进展(公开资料) BAY 1817080是拜耳在研的一款P2X3拮抗剂,正在开发用于治疗子宫内膜异位症、慢性咳嗽、膀胱过动症等。在治疗慢性咳嗽的一项I/IIa期临床研究中,与安慰剂相比,BAY 1817080使患者24小时咳嗽次数减少,而且耐受性良好。 朗来科技的QR052107B是一款新一代高选择性P2X3受体拮抗剂,拟开发用于难治/不明原因的慢性咳嗽治疗。临床前研究显示,QR052107B在疼痛、瘙痒等动物药效模型中表现出了明确的药效作用,而且QR052107B还具有在保持治疗有效性的同时解决味觉障碍的不良反应、更好的安全性等潜在优势。去年10月,朗来科技启动II期临床试验,评估QR052107B在难治性或不明原因慢性咳嗽患者中的疗效和安全性。 目前全球约有2800万慢性咳嗽患者,其中大约1000万患者患有RCC时间超过一年。RCC严重影响生活质量,患者可能出现抑郁、尿失禁、疼痛、肋骨骨折、社交退缩和失眠等,临床上存在巨大的未满足需求。希望以上药物研发进展顺利,早日造福患者。 主要参考资料: 1、 www.reuters.com/markets/deals/gsk-buy-canadas-bellus-health-2-bln-2023-04-18/; 2、 Safety and Efficacy of BAY 1817080, a P2X3 Receptor Antagonist, in Patients with Refractory Chronic Cough (RCC). From https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2020.201.1_MeetingAbstracts.A7648; 3、 UPDATED: Pfizer fields a CRL for a $295M rare disease play, giving rival a big head start. 智药研习社近期直播报名来源:CPHI制药在线声明:本文仅代表作者观点,并不代表制药在线立场。本网站内容仅出于传递更多信息之目的。如需转载,请务必注明文章来源和作者。投稿邮箱:Kelly.Xiao@imsinoexpo.com▼更多制药资讯,请关注CPHI制药在线▼点击阅读原文,进入智药研习社~

并购临床3期上市批准临床结果申请上市

分析

对领域进行一次全面的分析。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

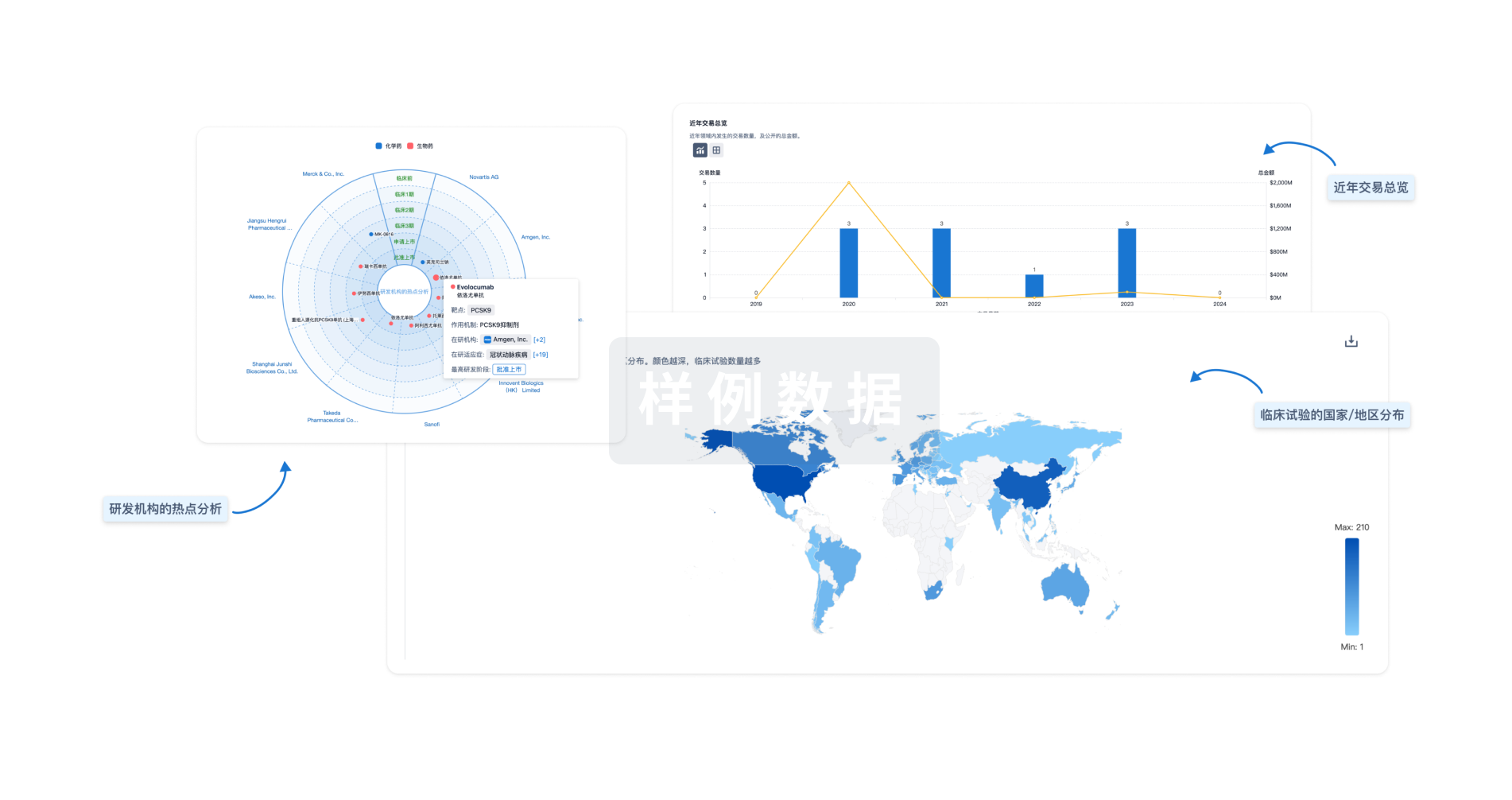

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用