预约演示

更新于:2025-05-07

Congenital Bilateral Aplasia of Vas Deferens

先天性双侧输精管发育不全

更新于:2025-05-07

基本信息

别名 Absence of Vas Deferens、Absent Vasa、CAVD + [13] |

简介 An autosomal recessive disorder that is associated with mutation(s) in the CFTR gene, encoding cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Mutation(s) in the same gene are associated with cystic fibrosis. |

关联

1

项与 先天性双侧输精管发育不全 相关的药物靶点 |

作用机制 DPP-4抑制剂 |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批国家/地区 印度 |

首次获批日期2019-10-12 |

6

项与 先天性双侧输精管发育不全 相关的临床试验NCT06200870

Iron Deficiency as a Promoter of Intra-leaflet Haemorrhage-induced Aortic Valve Calcification

Calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD) is a highly prevalent, disabling and costly disorder with generally poor long-time outcomes once critical stenosis presents with symptoms. Elucidating viable therapeutic strategies for CAVD is pressing. Valvular interstitial cells (VICs) control the structure and function of aortic valve. Intra-leaflet haemorrhage (IH), commonly occurring in histologically stenotic aortic valves, while, in 2019, researchers pointed that iron deposits also presented obviously healthy valves. In line with this, later exploration from vitro showed that iron stimulation alone could not promote VICs calcification. Iron deficiency (ID) is a frequent co-morbidity in multiple chronic cardiovascular diseases such as CAVD; up to 50% of patients with severe aortic stenosis present ID. Data from a small clinical study in patients undergoing TAVI showed those in ID status appeared much higher mean transaortic gradient; whereas no studies have assessed the correlation between ID and aortic valve remodelling and dysfunction progress itself. Here, the investigators aim to investigate for a tentative correlation between ID and human aortic valve remodeling and dysfunction.

开始日期2024-01-01 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT06045702

Establishment of a Primary Epididymal Cell Model From Epididymal Samples to Study CFTR Gene Regulation

The aim of this observational study is to better understand the role and involvement of the regulatory elements of the CFTR gene, with the aim of better describing the 3D organisation of chromatin at the CFTR locus in epididymal cells in patients with male infertility of any kind, or with cystic fibrosis or bilateral agenesis of the vas deferens, requiring scheduled surgery.

The main questions it aims to answer are:

to better characterise this 3D organisation of the CFTR locus, the study of regulatory elements in primary epididymal cells is the most relevant and realistic model.

to gain a better understanding of the regulation of the CFTR gene in epididymal cells in order to gain a better understanding of the pathology of male infertility caused by bilateral agenesis of the vas deferens, a symptom and also a borderline form of cystic fibrosis.

Participants will Epididymal samples will be taken by a urologist for the AMP department during the planned surgery. The rest of the samples taken will be recovered for research purposes, with the aim of recovering the epididymal cells contained in the sample. This is in no way an additional procedure and will have no impact on the patient's health..

The main questions it aims to answer are:

to better characterise this 3D organisation of the CFTR locus, the study of regulatory elements in primary epididymal cells is the most relevant and realistic model.

to gain a better understanding of the regulation of the CFTR gene in epididymal cells in order to gain a better understanding of the pathology of male infertility caused by bilateral agenesis of the vas deferens, a symptom and also a borderline form of cystic fibrosis.

Participants will Epididymal samples will be taken by a urologist for the AMP department during the planned surgery. The rest of the samples taken will be recovered for research purposes, with the aim of recovering the epididymal cells contained in the sample. This is in no way an additional procedure and will have no impact on the patient's health..

开始日期2023-09-01 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT04521452

An Open-label, Randomized Study of Inhibitory Effect of Evogliptin, the Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor, on the Progression of Aortic Valve Calcification in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Mild-to-moderate Aortic Stenosis

The purpose of this study is to assess an inhibitory effect of Evogliptin on the progression of mild-to-moderate aortic stenosis in patients with T2DM and calcific aortic stenosis.

开始日期2020-09-01 |

申办/合作机构  Asan Medical Center Asan Medical Center [+1] |

100 项与 先天性双侧输精管发育不全 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 先天性双侧输精管发育不全 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 先天性双侧输精管发育不全 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

1,279

项与 先天性双侧输精管发育不全 相关的文献(医药)2025-06-01·Journal of Clinical & Translational Endocrinology

Testicular function and fertility outcomes in males with CF: A multi center retrospective study of men with congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens based on CFTR mutation status

Article

作者: Leitner, Danielle Velez ; Vij, Sarah C ; Weiss, Marissa ; Cannarella, Rossella

2025-04-15·Cardiovascular Research

The N6-methyladenosine demethylase ALKBH5 is a novel epigenetic regulator of aortic valve calcification

Article

作者: Hu, Xiao ; Zhu, Dongxing ; Zhong, Guoli ; Li, Kun ; Lan, Lan ; Fu, Xiaodong ; He, Shengping ; Yu, Hongjiao ; Macrae, Vicky E ; Yuan, Liang ; Zhao, Huan ; Wang, Yueheng ; Xie, Yuchen ; Chen, Guojun

2025-04-01·ESC Heart Failure

Increased calcification by erythrophagocytosis in aortic valvular interstitial cells

Article

作者: Franco‐Cereceda, Anders ; Qin, Zihan ; Bäck, Magnus ; Pawelzik, Sven‐Christian

4

项与 先天性双侧输精管发育不全 相关的新闻(医药)2024-07-06

·药时代

主动脉瓣钙化(CAVD)是一种慢性进行性疾病,早期时表现为瓣膜增厚,但到后期可能进展为瓣膜受损,血流受阻。临床症状上表现为呼吸困难,胸痛甚至昏厥。据可统计的数据显示,目前全球被诊断为轻中度CAVD患者已经达到450万人,到2040年这一数字预计增长到760万人。由于大部分轻中度患者在临床上没有症状,也没有去医院就诊,所以这个数字有被低估的可能。

面对这一严峻形式,我们可用的手段却十分有限。目前已有的治疗方式包括开胸手术(SAVR)和微创置换术 (TAVR),这两种方式最终都是通过对主动脉瓣置换达到治疗效果。对开胸手术而言,不仅面临巨大的手术风险,还会在之后产生多种并发症,例如瓣膜血栓和心内膜炎。微创手术虽然好一点,高昂的治疗费用也会让患者及家庭背负巨大的负担。据了解,国外通过微创手术治疗CAVD的总治疗费用高达11万美元。

面对这一未被满足的临床需求,我们希望通过此次机会向大家推荐两款具有First In Class潜力的CAVD药物。第一款是靶向DPP4i+SGLT2i的口服药物组合,目前准备进入临床II期。DPP4i可以通过影响IGF-1,进而阻断瓣膜间质细胞(Valvular interstitial cells)向成骨细胞样细胞(osteoblast-like cells)的分化。SGLT2i虽然获批适应症为糖尿病,但它也是一类众所周知的心脏保护药物,达格列净和恩格列净的IV临床试验已经显示这一点。项目方通过将这两种药物组合,在CAVD治疗上达到1+1>2的效果。

第二款产品是一个靶向TNAP的口服小分子抑制剂,目前处于PCC阶段,正在开展毒理研究相关的工作。药物具有高度选择性,并且在体外酶活试验、细胞试验以及小鼠模型上均观测到相关活性数据。

如果您对以上两款资产感兴趣,欢迎随时与我们联系。我们将高效地推进您与项目方的合作。

项目简介

项目代号:BP-20240531-OR-047-004

项目名称:治疗CAVD临床II期FIC潜力小分子新药

适应症:主动脉瓣钙化(CAVD)

药物类型:小分子

靶点:DPP4+SGLT2

产品阶段:准备进入临床II期

专利布局:PCT计划2024年递交

项目亮点:不同机理药物联合,具有协同作用

合作需求:license(大中华区)

作用机理

项目简介

项目代号:BP-20240531-OR-047-002

项目名称:治疗CAVD临床前FIC潜力小分子新药

药物类型:小分子

靶点:TNAP(Tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase)

适应症:主动脉瓣钙化(CAVD)

产品阶段:临床前(毒理研究进行中)

专利布局:PCT计划2024年递交

项目亮点:候选分子具有高度选择性,在动物模型中观察到药效

合作需求:license(大中华区)

作用机理

如果您对该项目感兴趣,欢迎与我们联系!

请注明项目代号:BP-20240531-OR-047

我们将与您详细探讨。谢谢!

联系人:Richard

电话:17821449819

微信:DrugTimes_BD

邮箱:BD@drugtimes.cn

药时代BD项目 | ~70个在研产品寻找licensing机会

药时代BD-030项目 | IND ready阶段月制剂减重药物GDF15融合蛋白寻求合作

药时代BD-112项目 | 急性痛风、化疗引发的腹泻(CID)领域临床Ⅱ期重组人白介素-1受体拮抗剂寻求合作

药时代BD-093项目 | 全球首创治疗r/r T-ALL/LBL及AML的自体CD7-CAR-T寻求合作

药时代BD-092项目 | 高活性,低风险THRβ靶向NASH新药寻求合作

药时代BD-038项目 | VEGF靶向单抗III期眼病蓝海项目

药时代BD-041项目 | 高结合力、高效能PD-1xPD-L1双抗I期项目

药时代BD-043项目 | 安全、高效PD-1xTGF-β双抗肿瘤项目寻求合作

药时代BD-052项目 | FLT3靶向临床III期口服小分子寻求合作

药时代BD-需求011 | 寻找肿瘤(实体瘤)或自免疫领域的创新药资产

药时代BD-需求012 | 寻找宫腔镜和子宫内膜异位的相关资产

药时代BD-需求014 | 寻找前列腺癌和儿童罕见病相关的创新药资产

药时代BD-需求015 | 寻找消化道疾病相关的资产

药时代BD-需求016 | 寻找呼吸、免疫、心脑血管、代谢、肿瘤等相关创新药资产

药时代BD-需求 | 寻找儿科罕见病创新药资产

药时代BD需求 | TOP10跨国药企寻找GLP-1、JAK、肥胖、心血管、类风湿等差异化后期产品

药时代BD-需求 | MNC企业寻找胰腺癌、结直肠癌领域的早期抗体

药时代BD需求 | 全球MNC药企寻找一系列创新药产品

药时代BD-需求 | 资金充足的biotech寻找眼科相关的优质创新药资产及公司

药时代BD-需求 | 知名上市公司寻找BIC潜力ADC项目

药时代BD | 药企Co-development需求对接

药时代BD | 企业出售或兼并购需求对接

了解更多好项目,请点击阅读原文

临床2期引进/卖出临床1期

2024-06-05

Researchers have now proposed a molecular mechanism that links amyloid deposition in the aortic valve with degenerative calcification. They also theorize that other risk factors for CAVD, such as high blood levels of lipoprotein, can contribute to calcification both directly and indirectly through the mechanisms that involve amyloid accumulation.

Calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD) is the major heart valve disease that afflicts nearly 10 million patients globally with an annual mortality exceeding 100,000, and the numbers continue to rise. In CAVD, microcrystals of hydroxyapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral) deposit onto the heart valve leaflets and impair cardiac function. The disease has a dismal prognosis with most untreated patients dying two years after diagnosis. Currently, the only available treatment is surgical aortic valve replacement, which is not appropriate for all patients.

While previous studies of the histology samples from explanted calcified aortic valves have found amyloid deposits in or near calcified areas, the causal relationship between amyloid deposition and calcification is unclear.

Researchers from Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, in collaboration with clinical cardiologists from New York University and University of Texas Houston, have now proposed a molecular mechanism that links amyloid deposition in the aortic valve with degenerative calcification. They also theorize that other risk factors for CAVD, such as high blood levels of lipoprotein, can contribute to calcification both directly and indirectly through the mechanisms that involve amyloid accumulation.

Harnessing the "resolution revolution" in cryogenic electron microscopy, groups of researchers around the world were able to determine hundreds of structures of patient-derived protein aggregates called amyloid fibrils. Such fibrils are associated with major human diseases including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, diabetes, and heart diseases such as atherosclerosis and calcific aortic valve disease. "We noticed that the unique geometry of amyloid fibrils, with their periodic arrays of acidic residues on the surface, provides a perfect match for the precursors of calcium phosphate crystals that deposit in the heart valve and impair its normal function," explained corresponding author Olga Gursky, PhD, professor of pharmacology, physiology & biophysics at the school.

The researchers propose that amyloid deposits, which are often found adjacent to calcified areas of the heart valve, can modulate CAVD and accelerate degenerative calcification. This implies that blocking amyloid formation may be a much-needed novel therapeutic target for CAVD and, potentially, other diseases involving degenerative calcification and amyloid formation, such as Alzheimer' disease.

"We hope that a better understanding of molecular mechanisms and drivers of degenerative biomineralization will help identify new therapeutic targets for major human diseases, such as calcific aortic valve disease," adds Gursky.

2024-01-27

·生物探索

引言主动脉瓣钙化导致小叶硬度增加,从而导致钙化性主动脉瓣疾病(CAVD)的发展。然而,钙化的分子和细胞机制尚不清楚。2024年1月24日,华中科技大学王勇军、吴杰及解放军总医院曹丰共同通讯(韩东、周廷文及李立夫为本文的共同第一作者)在Circulation(IF 38)在线发表题为“AVCAPIR: A Novel Procalcific PIWI-Interacting RNA in Calcific Aortic Valve Disease”的研究论文,该研究发现了一种新的主动脉瓣钙化相关的PIWI相互作用RNA (piRNA;AVCAPIR)可以增加瓣膜钙化并促进CAVD进展。研究发现AVCAPIR在AVC期间显著上调,对CAVD具有潜在的诊断价值。AVCAPIR缺失显著改善了高胆固醇饮食饲养的ApoE - / -小鼠的AVC,表现为主动脉瓣叶厚度和钙沉积减少,超声心动图参数改善(经瓣喷射速度峰值和平均经瓣压力梯度降低,主动脉瓣面积增加),主动脉瓣成骨标志物(Runx2和Osterix)水平降低。这些结果在成骨培养基诱导的人瓣膜间质细胞中得到证实。通过无偏倚蛋白-RNA筛选和分子验证,发现AVCAPIR直接与FTO(脂肪质量和肥胖相关蛋白)相互作用,随后阻断其N6-甲基腺苷去甲基化酶活性。进一步的转录组学和N6-甲基腺苷修饰外转录组学筛选和分子验证证实,AVCAPIR阻碍了FTO介导的CD36 mRNA转录物的去甲基化,从而通过N6-甲基腺苷读取器IGF2BP1(胰岛素样生长因子2 mRNA结合蛋白)增强了CD36 mRNA的稳定性。反过来,AVCAPIR依赖性CD36的增加在蛋白水平上稳定了其结合伙伴PCSK9(蛋白转化酶枯草素/kexin 9型),这是一种原钙化基因,从而加速了AVC的进展。该研究发现了一种通过RNA表观遗传机制诱导AVC的新型piRNA,并为以piRNA为导向的CAVD治疗提供了新的见解。在过去的几年中,研究非编码RNA在心血管疾病中的关键调控作用的研究数量激增。之前的一系列研究也揭示了非编码RNAs在调节AVC。成骨重编程中的关键作用在不同类型的非编码RNA中,PIWI-相互作用RNAs (piRNAs)以3′-末端2′-O-甲基化为特征,已被确定为一类新的小非编码RNA,长度为21至35个核苷酸。piRNAs除了在哺乳动物种系中表达外,还在心血管细胞中表达,其在调节心血管各种病理生理过程中的功能作用已逐渐被认识。最近报道了一种与心肌肥厚相关的piRNA可促进病理性肥厚和心脏重塑此外,piRNAs是心脏分化、修复和再生的新型调节因子。尽管如此,关于piRNAs是否以及如何调节AVC成骨重编程的认识有限。越来越多的证据表明,CD36是一种多功能的B类清道夫受体,在心血管疾病中起着关键作用。CD36与动脉粥样硬化有关,其发病机制与CAVD相似。CD36+瓣膜内皮细胞与高脂血症引发的瓣膜炎症有关,被认为是主动脉瓣病变的重要初始过程。先前的报告显示CD36在主动脉瓣狭窄中的潜在病理作用,尽管如此,CD36在CAVD中的确切作用及其调控机制仍不清楚。模式图(Credit: Circulation)PCSK9 (proprotein converting ase subtilisin/ keexin type 9)被认为与肝脏和其他细胞膜上的低密度脂蛋白(LDL)颗粒受体结合并降解,从而阻止LDL颗粒的摄入和破坏。除了其在脂蛋白稳态中的基本作用外,PCSK9除了其调节血脂的作用外,其多效性作用已经越来越多地被认识到。值得注意的是,人们逐渐认识到,PCSK9功能丧失变异中低LDL-胆固醇水平的存在并不能完全解释其对CAVD的保护作用。因此,探索PCSK9表达的直接钙原和调节机制有望扩大CAVD的治疗范围。该研究探索了参与CAVD发病机制的功能性piRNA,并进一步剖析其在AVC中的作用机制。研究表明,AVC相关的piRNA (AVCAPIR)在体外和体内促进AVC。此外,AVCAPIR已被发现通过破坏FTO介导的CD36 mRNA转录物的m6A去甲基化来增强CD36/PCSK9轴。因此,AVCAPIR耗竭可能是CAVD的一种新的治疗策略,这些结果可以作为未来临床研究的路线图,以评估AVCAPIR耗竭对CAVD患者的潜在治疗效果。原文链接https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.065213责编|探索君排版|探索君文章来源|“iNature”End往期精选围观Nat Med | 黄荷凤院士/张静澜/徐晨明团队发表综合性无创产前筛查临床研究成果热文Science最新发布:全世界最前沿的125个科学问题热文Nature | 2024年值得关注的七项技术热文新发现推翻古老假说:梅毒微生物家族与人类共存已有数千年热文Nat Methods | 自主生物发光成像技术在真核生物中的创新进展

信使RNA

分析

对领域进行一次全面的分析。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

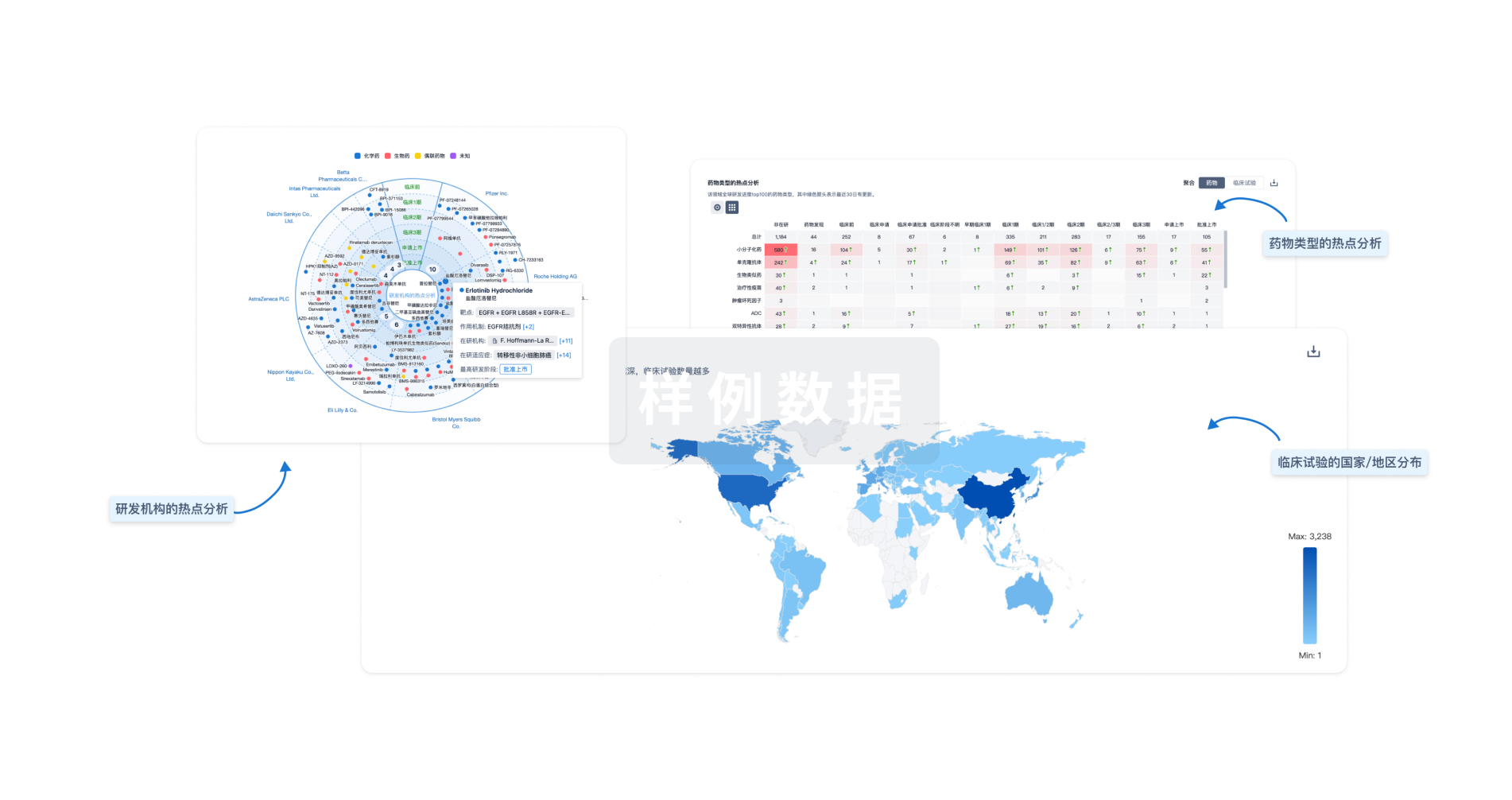

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用