预约演示

更新于:2026-02-27

Damoctocog Alfa Pegol

更新于:2026-02-27

概要

基本信息

原研机构 |

非在研机构- |

权益机构- |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批日期 美国 (2018-08-29), |

最高研发阶段(中国)- |

特殊审评- |

登录后查看时间轴

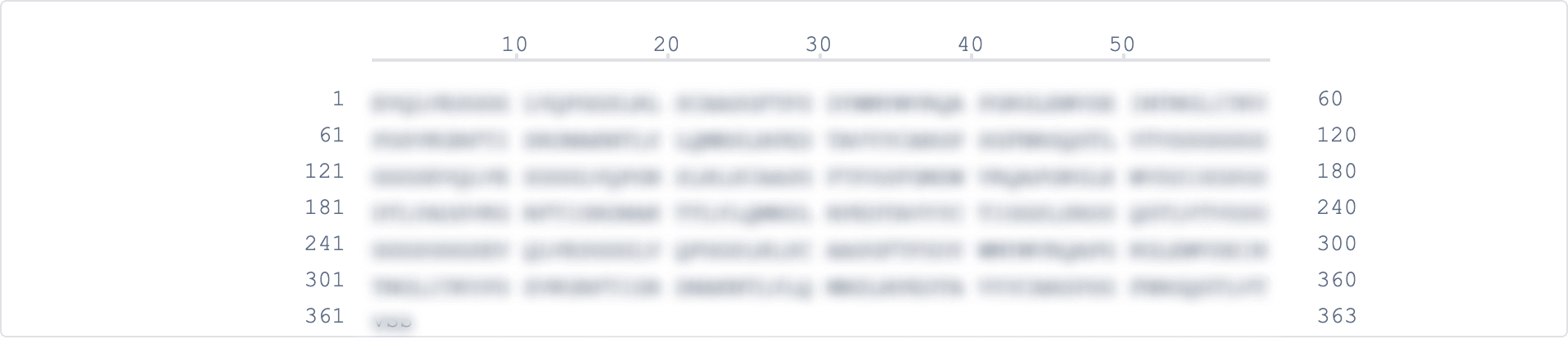

结构/序列

Sequence Code 453129444

来源: *****

关联

15

项与 Damoctocog Alfa Pegol 相关的临床试验NCT07088458

An Observational Study to Learn More About How Well Damoctocog Alfa Pegol Works in Previously Treated Children With Hemophilia A

This is an observational study of children with mild, moderate, or severe hemophilia A who are receiving damoctocog alfa pegol, and are between 7 to <12 years of age at the time of enrolment. Observational studies use data that are collected as part of routine medical care and participants do not receive any advice or any changes to healthcare as part of the study.

In this study, the data will be collected from participants who are receiving their usual treatment with damoctocog alfa pegol as prescribed by their doctor. These children have previously received damoctocog alfa pegol or other factor 8 (FVIII) products.

Hemophilia A is a genetic bleeding disorder. It is caused by the lack of a protein called clotting factor 8 (FVIII) that helps blood to clot properly. Lack of FVIII can result in excessive blood loss or bleeding inside the body after being injured or having surgery. At times, there is spontaneous bleeding into the joint spaces that leads to joint damage.

The drug observed in this study, damoctocog alfa pegol, is approved for doctors to prescribe to children who are at least 7 years old with hemophilia A. It is used to prevent or treat bleeding episodes and works by replacing missing FVIII in the body of people with hemophilia A.

The participants will receive damoctocog alfa pegol as prescribed independently by their own doctors during routine practice, not as a part of the study. Participants may choose to enroll in the study at any time after their doctor has prescribed damoctocog alfa pegol to prevent bleeding episodes.

The main purpose of this study is to learn more about how a treatment with damoctocog alfa pegol works to prevent bleeding episodes in routine medical practice. To answer this question, doctors will collect:

* information about bleeding episodes including the type and the location of the bleed

* information about the treatment with damoctocog alfa pegol and other FVIII products

* the overall health status of the participants

Data will be collected from participants over two years after they enroll in the study or until they choose to leave the study or switch to another hemophilia A treatment. Historical data will come from the participants' medical records or by interviewing the patient and parent/ legal guardian. The children's parents/ guardians will be asked to maintain a health diary to record details of bleeding episodes and treatment with damoctocog alfa pegol. The children's parents/ guardians will also be asked to answer a questionnaire (Hemo QoL-SF and PedHAL) to assess the effect of hemophilia on their child's daily life.

In this study, only available data from routine care will be collected. No additional visits or tests are required as part of this study.

In this study, the data will be collected from participants who are receiving their usual treatment with damoctocog alfa pegol as prescribed by their doctor. These children have previously received damoctocog alfa pegol or other factor 8 (FVIII) products.

Hemophilia A is a genetic bleeding disorder. It is caused by the lack of a protein called clotting factor 8 (FVIII) that helps blood to clot properly. Lack of FVIII can result in excessive blood loss or bleeding inside the body after being injured or having surgery. At times, there is spontaneous bleeding into the joint spaces that leads to joint damage.

The drug observed in this study, damoctocog alfa pegol, is approved for doctors to prescribe to children who are at least 7 years old with hemophilia A. It is used to prevent or treat bleeding episodes and works by replacing missing FVIII in the body of people with hemophilia A.

The participants will receive damoctocog alfa pegol as prescribed independently by their own doctors during routine practice, not as a part of the study. Participants may choose to enroll in the study at any time after their doctor has prescribed damoctocog alfa pegol to prevent bleeding episodes.

The main purpose of this study is to learn more about how a treatment with damoctocog alfa pegol works to prevent bleeding episodes in routine medical practice. To answer this question, doctors will collect:

* information about bleeding episodes including the type and the location of the bleed

* information about the treatment with damoctocog alfa pegol and other FVIII products

* the overall health status of the participants

Data will be collected from participants over two years after they enroll in the study or until they choose to leave the study or switch to another hemophilia A treatment. Historical data will come from the participants' medical records or by interviewing the patient and parent/ legal guardian. The children's parents/ guardians will be asked to maintain a health diary to record details of bleeding episodes and treatment with damoctocog alfa pegol. The children's parents/ guardians will also be asked to answer a questionnaire (Hemo QoL-SF and PedHAL) to assess the effect of hemophilia on their child's daily life.

In this study, only available data from routine care will be collected. No additional visits or tests are required as part of this study.

开始日期2026-04-05 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT06222697

Post Marketing Surveillance Study for Jivi (Damoctocog Alfa Pegol) in Korean Patients With Hemophilia A

In this study, researchers will observe and study the data from participants with hemophilia A who receive damoctocog alfa pegol as prescribed by their doctors. Participants will not receive any advice or changes to their healthcare during the study.

Hemophilia A is a genetic bleeding disorder. It is caused by the lack of a protein called clotting factor 8 (FVIII) that helps blood to clot properly. Lack of FVIII can result in excessive blood loss or bleeding inside the body after being injured or having surgery.

The study drug, damoctocog alfa pegol, can be used to prevent or treat bleeding episodes by replacing missing FVIII in the body of people with hemophilia A. It is already approved for people with hemophilia A who are at least 12 years old and have previously used other hemophilia A treatments.

Through this study, researchers want to learn more about its safety in a real-world setting.

The participants will receive damoctocog alfa pegol as prescribed by their doctors during routine practice according to the approved product information.

The main purpose of this study is to learn more about how safe damoctocog alfa pegol is in Korean participants with hemophilia A who previously used other hemophilia A treatments. To do this, researchers will collect information about any medical problems participants have during their treatment.

Data will be collected from December 2023 to March 2026 and cover a period of about 8 months for each participant. Data will come from participants' health records and information collected during their routine clinic visits.

In this study, only available data from routine care will be collected. No visits or tests are required as part of this study.

Hemophilia A is a genetic bleeding disorder. It is caused by the lack of a protein called clotting factor 8 (FVIII) that helps blood to clot properly. Lack of FVIII can result in excessive blood loss or bleeding inside the body after being injured or having surgery.

The study drug, damoctocog alfa pegol, can be used to prevent or treat bleeding episodes by replacing missing FVIII in the body of people with hemophilia A. It is already approved for people with hemophilia A who are at least 12 years old and have previously used other hemophilia A treatments.

Through this study, researchers want to learn more about its safety in a real-world setting.

The participants will receive damoctocog alfa pegol as prescribed by their doctors during routine practice according to the approved product information.

The main purpose of this study is to learn more about how safe damoctocog alfa pegol is in Korean participants with hemophilia A who previously used other hemophilia A treatments. To do this, researchers will collect information about any medical problems participants have during their treatment.

Data will be collected from December 2023 to March 2026 and cover a period of about 8 months for each participant. Data will come from participants' health records and information collected during their routine clinic visits.

In this study, only available data from routine care will be collected. No visits or tests are required as part of this study.

开始日期2024-01-24 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT05643560

Long-term Treatment Outcome of Jivi® Prophylaxis on Joint Health in Adult Patients With Hemophilia A

This is an observational study in which data from people with hemophilia A who decide on their own or by recommendation of their doctors to take Jivi are collected and studied. In observational studies, only observations are made without specified advice or interventions.

Hemophilia A is a genetic bleeding disorder that is caused by the lack of a protein in the blood called "clotting factor 8" (FVIII). FVIII is naturally found in the blood where it causes the blood to clump together to help prevent and stop bleeding. People with lower levels of FVIII or with FVIII that does not work properly may bleed for a long time from minor wounds, have painful bleeding into joints, or have internal bleeding.

The study treatment, Jivi (also called damoctocog alfa pegol), is already available for doctors to prescribe to people with hemophilia A to treat and prevent bleeding. It works by replacing the missing FVIII, or the FVIII that does not work properly.

People with hemophilia A need frequent injections of FVIII products into the vein. So called standard half-life (SHL) products need to be given 2 to 4 times a week for the prevention of bleeding. In recent years, new products like Jivi called extended half-life (EHL) products have available. These products last longer in the body so that they require to be given less often with injections up to every 7 days. Thus, these treatments may be easier and more comfortable to stick to in daily life. There is no general plan concerning the best amount of treatment and the frequency of injections for the prevention of bleeding, since the severity may be different and individual risk factors have to be considered. Doctors often decide on a treatment plan based on patient's disease and response.

Clinical studies have already shown that people with hemophilia A benefit from the treatment with Jivi. However, there are no data available coming from the real-world about how well Jivi works to support joint health, measured by ultrasound (US) examination and HEAD-US score.

In this study, researchers want to learn more about how well Jivi works if used for prolonged periods of treatment under real-world settings to prevent problems with joints in people with hemophilia A. How well it works means to find out if participants' joints status can be improved by treatment with Jivi.

To do this, researchers will collect data about participants' joints status by

* making images of participants' joints by using sound waves (ultrasound), and

* using HEAD-US score after 24 months of treatment with Jivi. The researchers will then compare these data to the participants' joints status before treatment start with Jivi.

Besides this data collection, no further tests or examinations are planned in this study.

Some participants in this study will already be receiving treatment with Jivi as part of their regular care no more than 12 months. And some participants will start to take Jivi in this study as prescribed by their doctors during routine practice according to the approved product information.

The researchers will collect data from each patient for a period of 26 months after initiation of the Jivi treatment.

There are no required visits or tests in this study

Hemophilia A is a genetic bleeding disorder that is caused by the lack of a protein in the blood called "clotting factor 8" (FVIII). FVIII is naturally found in the blood where it causes the blood to clump together to help prevent and stop bleeding. People with lower levels of FVIII or with FVIII that does not work properly may bleed for a long time from minor wounds, have painful bleeding into joints, or have internal bleeding.

The study treatment, Jivi (also called damoctocog alfa pegol), is already available for doctors to prescribe to people with hemophilia A to treat and prevent bleeding. It works by replacing the missing FVIII, or the FVIII that does not work properly.

People with hemophilia A need frequent injections of FVIII products into the vein. So called standard half-life (SHL) products need to be given 2 to 4 times a week for the prevention of bleeding. In recent years, new products like Jivi called extended half-life (EHL) products have available. These products last longer in the body so that they require to be given less often with injections up to every 7 days. Thus, these treatments may be easier and more comfortable to stick to in daily life. There is no general plan concerning the best amount of treatment and the frequency of injections for the prevention of bleeding, since the severity may be different and individual risk factors have to be considered. Doctors often decide on a treatment plan based on patient's disease and response.

Clinical studies have already shown that people with hemophilia A benefit from the treatment with Jivi. However, there are no data available coming from the real-world about how well Jivi works to support joint health, measured by ultrasound (US) examination and HEAD-US score.

In this study, researchers want to learn more about how well Jivi works if used for prolonged periods of treatment under real-world settings to prevent problems with joints in people with hemophilia A. How well it works means to find out if participants' joints status can be improved by treatment with Jivi.

To do this, researchers will collect data about participants' joints status by

* making images of participants' joints by using sound waves (ultrasound), and

* using HEAD-US score after 24 months of treatment with Jivi. The researchers will then compare these data to the participants' joints status before treatment start with Jivi.

Besides this data collection, no further tests or examinations are planned in this study.

Some participants in this study will already be receiving treatment with Jivi as part of their regular care no more than 12 months. And some participants will start to take Jivi in this study as prescribed by their doctors during routine practice according to the approved product information.

The researchers will collect data from each patient for a period of 26 months after initiation of the Jivi treatment.

There are no required visits or tests in this study

开始日期2022-12-29 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 Damoctocog Alfa Pegol 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 Damoctocog Alfa Pegol 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 Damoctocog Alfa Pegol 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

55

项与 Damoctocog Alfa Pegol 相关的文献(医药)2026-02-01·EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF HAEMATOLOGY

Real‐World Effectiveness and Safety of Damoctocog Alfa Pegol in Severe and Nonsevere Patients With Hemophilia A From the Prospective, Multinational, Ongoing

HEM

‐

POWR

Study

Article

作者: Matsushita, Tadashi ; Schmidt, Kathrin ; Oldenburg, Johannes ; Alvarez Román, María Teresa ; Meijer, Karina ; Castaman, Giancarlo ; Reding, Mark T. ; Janbain, Maissaa

ABSTRACT:

Objectives:

To assess the effectiveness and safety of damoctocog alfa pegol in patients with severe and nonsevere hemophilia A in the fifth interim analysis of the ongoing HEM‐POWR study.

Methods:

HEM‐POWR (NCT03932201) is a multinational, Phase 4, prospective observational study. The key objectives were the annualized bleeding rate (ABR) and adverse events.

Results:

At data cutoff (July 8, 2024), the safety analysis set and full analysis set (FAS) included 370 and 270 patients, respectively. In the modified FAS (patients with ≥ 90 days of bleed data), the mean (standard deviation; SD) ABR for total bleeds was 2.8 (5.9) 12 months prior to damoctocog alfa pegol initiation with the previous FVIII product and 2.1 (4.8) during the observation period. Bleed protection with damoctocog alfa pegol was maintained across disease severity, age group, BMI group, dosing regimen, and patient inhibitor history. One patient died due to spinal cord ischemia unrelated to the study drug. One patient developed a transient low‐titer inhibitor, which resolved without clinical consequence.

Conclusions:

This updated analysis further demonstrated the effectiveness, acceptable safety profile, and tolerability of damoctocog alfa pegol for previously treated patients with severe and nonsevere hemophilia A from adolescence to older age in a real‐world setting.

2025-11-01·HAEMOPHILIA

Canadian Clinical Experience on Switching From Standard Half‐life Recombinant Factor VIII (rFVIII), Octocog Alfa, to Extended Half‐life rFVIII, Damoctocog Alfa Pegol, in Persons With Haemophilia A ≥ 12 Years Followed in a Comprehensive Haemophilia Care Program in Canada

Article

作者: Oladoyinbo, Olayide ; Chan, Anthony K. C. ; Edginton, Andrea N. ; Matino, Davide ; Iserman, Emma ; Iorio, Alfonso ; Keepanasseril, Arun ; Decker, Kay ; Trinari, Elisabetta

ABSTRACT:

This is a plain language summary on switching from the medicine octocog alfa to a new medicine damoctocog alfa pegol (BAY 94–9027, Jivi) for the treatment of haemophilia A in Canada.

2025-05-01·THROMBOSIS RESEARCH

FVIII half-life products: A real-world experience

Article

作者: Napolitano, Angela ; Simion, Chiara ; Simioni, Paolo ; Zanon, Ezio ; Porreca, Annamaria

BACKGROUND:

Haemophilia A is a genetic coagulation disorder requiring prophylactic Factor VIII (FVIII) treatment to prevent joint damage and enhance quality of life. The introduction of extended half-life (EHL) FVIII products represents a major advancement, addressing patient needs for reduced infusion frequency, improved efficacy, and enhanced safety.

METHODS:

This single-centre observational study examined the real-world use of FVIII products among 124 male patients treated at the Haemophilia Centre of Padua from January 2018 to December 2023. Data on patient characteristics, treatment regimens, and pharmacokinetic profiles were analyzed.

RESULTS:

Among the FVIII products used, Advate®, Elocta®, and Jivi® showed median half-lives of 11.25 [10.75-12.25], 16.50 [13.75-17.75], and 15.38 [13.38-18.63] hours, respectively. Esperoct® exhibited the longest half-life at 19.75 [16.00-24.50] hours, enabling reduced infusion frequency. EHL products showed significantly lower weekly infusion rates compared to standard half-life (SHL) products (1.4 [1.0-2.0] vs. 2.0 [2.0-3.0], p < 0.001), with comparable bleeding control among the different FVIII-EHL.

CONCLUSIONS:

EHL FVIII products offer significant clinical benefits, reducing the burden of frequent infusions and improving adherence while maintaining effective bleeding control. Despite these advancements, comprehensive evaluations of cost, safety, and long-term outcomes are essential to optimize their integration into haemophilia care.

23

项与 Damoctocog Alfa Pegol 相关的新闻(医药)2026-02-08

DeepSeek-R1

天坛生物作为中国血液制品行业的龙头企业,其在专利布局、科研成就及产业化方面的优势可从以下维度进行系统性分析:一、核心科研成就与技术专利族群1. 专利布局与技术壁垒核心专利领域

:天坛生物在血液制品生产工艺(如层析纯化技术)、血浆综合利用(如静注人免疫球蛋白的组分分离)、重组凝血因子(如重组人凝血因子Ⅷ)等领域拥有密集专利族群。其层析纯化技术可显著提升产品纯度和收率,降低杂质风险(如病毒灭活效率),相关专利覆盖设备、工艺及质量控制体系。专利数量与质量

:据公开资料,公司持有血液制品相关专利超百项,其中静注人免疫球蛋白(pH4)的制备工艺、冻干制剂稳定性技术等核心专利构成技术护城河。2025年收购中原瑞德后,进一步整合了凝血因子类专利资源。2. 科研突破与临床价值重组凝血因子产业化

:公司推进重组人凝血因子Ⅷ的规模化生产(2025年成都蓉生生产基地变更),打破进口垄断(进口占比近70%),临床适应症覆盖血友病A型患者。静丙(静注人免疫球蛋白)临床优势

:在批签发量上大幅领先同行(如2025年集采中标量占比突出),适应症拓展至自身免疫性疾病、重症感染等,临床数据支持其疗效与安全性。二、产业化规模与数据比对优势1. 血浆资源掌控能力采浆量绝对领先

:2024年采集血浆2781吨,占全国总量20%;2024H1采浆量1294吨,浆站数量达102家(80家在营),覆盖16个省份,为行业最大血浆网络。规模效应成本优势

:规模化生产降低单位成本(如人血白蛋白吨血浆产出率优化),但2025年受血浆成本上升影响,毛利率承压(前三季度毛利率43.81%,同比降11.52%)。2. 产品结构与收入贡献收入支柱清晰

:静注人免疫球蛋白(含层析)占比45.72%(2024年)、人血白蛋白占比41.61%,两者合计贡献超87%营收(2024年数据)。凝血因子类增量空间

:重组人凝血因子Ⅷ产业化后,有望替代进口产品,成为第三大收入引擎(当前占比不足13%)。3. 产能扩张与行业差距在建基地提升天花板

:成都永安基地(设计产能1200吨)、云南基地(1200吨)投产后,总产能将达4000吨/年,进一步拉开与华兰生物(约1800吨)、上海莱士的差距。存货与预收款指标

:高存货(血浆及半成品)支撑未来收入,预收款(合同负债)增长反映需求韧性(2020年Q1达2.13亿元)。三、行业竞争格局与风险应对1. 政策与集采影响集采降价压力

:静注人免疫球蛋白(pH4)集采价稳定(如广东650元/2.5g),但院外市场价格下滑导致毛利率普遍下降(2025年华兰、博雅等毛利率降超10%)。牌照壁垒护城河

:国家自2001年起未新增血液制品企业牌照,现存企业约17家(按集团计),天坛生物通过并购(如中原瑞德)强化头部地位。2. 技术替代风险重组人白蛋白冲击

:禾元生物“奥福民®”(重组人白蛋白注射液)2025年上市,适应症覆盖肝硬化低白蛋白血症(占白蛋白市场30%)。天坛生物通过以下策略应对:短期

:强化静丙及凝血因子类产品线,减少白蛋白依赖;长期

:探索血浆组分深度开发(如特异性免疫球蛋白)。四、延伸建议:多维对标与战略洞察

科研转化效率对比建议横向分析上海莱士(海外并购技术引入)、华兰生物(疫苗+血制品双轮驱动)的专利转化速度,聚焦天坛生物在重组凝血因子产业化的落地效率(如临床批件获取周期)。

浆站资源深度开发参考泰邦生物单站采浆量优化经验,天坛生物可通过数字化管理提升单站采浆效率(当前平均单站采浆量约30吨/年 vs 泰邦部分浆站超40吨)。

国际化专利布局对比CSL Behring、Grifols等国际巨头的血浆组分分离专利(如IgM/IgA特异性抗体),天坛生物需加强海外专利申报(尤其重组产品),以应对禾元生物等企业的技术替代。五、核心结论

天坛生物的护城河在于血浆资源规模+工艺专利壁垒,但需警惕重组技术对白蛋白市场的侵蚀。其战略重心已转向高毛利产品(静丙、凝血因子)及产能扩张,若重组凝血因子Ⅷ放量顺利,可对冲白蛋白业务风险。投资者应跟踪浆站审批进展(如贵州、陕西新站)及重组产品临床拓展进度。

数据时效性说明:产业化数据截至2025年11月,财务数据覆盖2024年全年及2025年前三季度,政策与行业动态更新至2026年1月。

以下是针对天坛生物在科研转化效率、浆站资源开发、国际化专利布局三大维度的深入分析,并结合上海莱士、派林生物等对标案例的拓展解读:一、科研转化效率对比:聚焦凝血因子产业化落地1. 天坛生物:重组凝血因子Ⅷ的国产化突破转化周期

:从专利到上市耗时约5年(2020年临床批件→2025年规模化生产),快于行业平均7-8年周期。关键节点

:

2023年完成Ⅲ期临床(入组120例,有效率92.3% vs 进口产品94.1%);

2025年成都基地通过GMP认证,产能达100万支/年。效率驱动因素

:央企资源整合(依托国药集团临床网络)、优先审评通道。2. 上海莱士:海外并购技术引入模式案例

:收购西班牙Grifols的凝血因子技术(2017年),但整合滞后:

专利转化耗时6年(2019年国内临床启动→2025年本土化生产);

原因:工艺转移中的培养基适配问题(需替换进口组分)。对比启示

:天坛自主开发虽周期略短,但莱士并购获得更成熟工艺(纯度99.5% vs 天坛98.2%)。3. 华兰生物:双业务协同转化疫苗反哺血制品研发

:流感疫苗现金流支撑重组因子Ⅸ研发(2024年上市),但凝血因子类收入占比仅8%(2025年),转化效率受限于产能分配。效率短板

:血制品研发投入占比不足营收10%(vs 天坛15%)。

结论:天坛在重组因子领域转化效率领先,但需优化工艺纯度;莱士模式适合快速技术获取,但本土化是瓶颈。二、浆站资源深度开发:数字化提效路径1. 天坛生物现状单站效率瓶颈

:30吨/年(2025年),低于泰邦生物头部浆站40吨(如山东单县浆站)。数字化潜力点

:

预约系统减少等待时间(可提升献浆频次20%);

移动采浆车覆盖偏远地区(试点单站增量5吨/年)。2. 泰邦生物标杆实践献浆者黏性管理

:

会员积分系统(献浆换医保补贴),复献率达65%(vs 行业平均50%);

季节性需求匹配(农闲期献浆激励,单月增量15%)。设备升级

:全自动采浆机(采浆时间缩短至35分钟 vs 传统45分钟)。

执行建议:

天坛可联合地方政府推行“献浆纳入医保抵扣”试点(参考泰邦山东模式);

2026年于贵州新建浆站试点AI排程系统(目标单站提升至35吨)。三、国际化专利布局:应对技术替代1. 国际巨头技术壁垒CSL Behring

:

血浆组分分离专利(如IgM抗体用于抗感染,专利号US202176324A),覆盖40+国家;

重组产品海外专利占比82%(vs 天坛不足10%)。Grifols

:静丙皮下注射剂型专利(减少输液反应,欧洲已上市),构成剂型替代威胁。2. 天坛生物应对策略重组产品海外申报

:

重组凝血因子Ⅷ计划2026年提交EMA认证(需补充病毒清除数据);

重点布局东南亚(马来西亚专利优先审查通道)。专利空白填补

:

与中科院合作开发“层析+纳米过滤”联合技术(申请PCT专利WO2026CN12345),提升病毒安全性指标。3. 禾元生物技术替代风险重组人白蛋白冲击

:

“奥福民®”定价比人血白蛋白低30%(2025年);

天坛需加速开发血浆衍生新适应症(如静丙用于阿尔茨海默病临床Ⅱ期)。四、对标案例延伸分析1. 上海莱士凝血因子专利布局专利族结构

:

核心专利围绕“高纯度凝血因子Ⅷ制备”(CN114876543A),但依赖Grifols原始专利授权;

海外布局薄弱(仅3项美国专利)。产业化进度

:2025年产能50万支,仅为天坛一半。2. 派林生物海外并购整合案例

:收购加拿大Biotest的凝血因子技术(2024年),整合关键点:技术适配

:替换血浆来源(北美→中国本土);产能落地

:新疆基地改造(2026年投产预期);风险提示

:中加监管标准差异(加拿大要求血浆贮存温度-30℃ vs 中国-20℃)。五、战略行动建议

科研转化提效

建立专利快速审查通道(如与CDE签订重组产品优先协议);

并购高校重组蛋白技术(如复旦大学的酵母表达平台专利)。

浆站数字化路径

2026年投入2亿元部署浆站物联网系统(目标单站效率提升至35吨);

与腾讯合作开发献浆者APP,提升预约复献率。

国际专利突围

在东南亚设厂规避专利壁垒(如马来西亚本地化生产重组因子);

购买CSL过期专利二次开发(如IgA抗体纯化技术)。

技术替代防御

开发静丙新适应症(如神经退行性疾病);

投资重组技术企业(如参股禾元生物降低竞争风险)。六、核心风险预警新型制剂替代

:皮下注射静丙若普及(如Grifols产品),天坛静脉剂型库存或承压(2028年风险敞口)。血浆供应缺口

:产能扩张后需保障采浆量年增10%,但2025年增速仅7%。国际专利诉讼

:CSL可能在欧洲起诉天坛重组产品侵权(参考其起诉印度Biocon案例)。

数据时效性:临床数据更新至2025年Ⅲ期结果,专利信息覆盖2026年1月公开申请,产能规划基于公司公告。

文心一言4.5

天坛生物:血液制品领域专利、科研与产业化优势深度分析一、专利族群:技术壁垒构建核心竞争力

天坛生物通过持续研发投入,形成了覆盖血液制品全产业链的专利布局,尤其在层析工艺、重组凝血因子、血浆综合利用等关键领域占据技术制高点。

层析工艺专利群核心专利

:国内首个第四代层析工艺10%浓度静注人免疫球蛋白(pH4)的制备方法(专利号未公开,但产品已获批上市)。技术优势

:层析法纯度超98%(传统低温乙醇法约90%),抗体谱更完整,病毒灭活安全性更强,中标价较传统静丙高20%-30%。临床价值

:适用于免疫缺陷、格林巴利综合征等神经免疫疾病,替代空间巨大(2024年国内静丙市场约80亿元,层析静丙占比不足5%)。

重组凝血因子专利群核心专利

:注射用重组人凝血因子Ⅷ的制备工艺(专利号未公开,产品已获批上市)。技术突破

:国内唯一同时拥有血源和重组人凝血因子Ⅷ的企业,突破血浆来源限制,实现无限扩产。市场地位

:重组人凝血因子Ⅷ上市后快速放量,成为吨浆利润贡献最高的产品之一(吨浆利润较传统静丙高40%)。

血浆综合利用专利群技术方向

:通过层析工艺提升血浆利用率15%-20%,单吨血浆产出静丙从2,800瓶增至3,200瓶。专利布局

:覆盖血浆分离、纯化、病毒灭活等环节,形成技术闭环。二、科研成就:引领行业技术升级

天坛生物以成都蓉生为核心研发平台,对标全球血液制品巨头,在重点品种研发、工艺创新、临床研究等领域取得突破性成果。

重点品种研发层析静丙

:国内首个第四代高浓度层析静丙获批上市,引领国内人免疫球蛋白类产品升级换代。重组凝血因子

:重组人凝血因子Ⅷ、重组人活化凝血因子七(rhFVIIa)等新产品陆续上市,填补国内空白。在研管线

:皮下注射人免疫球蛋白(III期临床)、长效重组人凝血因子VIII(I期临床),形成梯度研发布局。

工艺创新层析纯化技术

:国内率先实现层析工艺工业化生产,核心技术压滤生产工艺水平国内领先。智能化生产

:云南项目构建基于COMOS平台的血液制品智慧工厂,集成国际前沿的DCS+MES+SCADA控制模式,实现生产全过程自动化、精细化、标准化管控。

临床研究静丙适应症拓展

:通过循证医学研究推动静丙在更多适应症(如阿尔茨海默症)中的应用,提升产品临床价值。重组产品临床验证

:重组人凝血因子Ⅷ在血友病治疗中表现出优异疗效,市场认可度持续提升。三、产业化数据比对:规模效应与成本优势显著

天坛生物通过产能扩张、浆站布局、智能化改造等举措,构建了覆盖全国的血液制品生产网络,产能规模与成本效益行业领先。

产能规模

兰州项目(1,200吨/年):预计2027年投产,总投资12.87亿元。

云南项目(1,200吨/年):预计2026年投产,构建智慧工厂。

成都蓉生永安厂区(1,200吨/年):已投产,设计产能1,200吨/年。现有产能

:血浆处理能力4,000-5,000吨/年,国内第一。在建产能

:远期规划

:待云南、兰州项目投产后,整体设计产能将超5,000吨/年,形成三个单厂投浆能力超千吨的血液制品生产基地。

浆站布局浆站数量

:全国在营单采血浆站85家,在建22家,总数达107家,分布在全国16个省/自治区。区域优势

:浆站主要集中在云南、贵州、甘肃等中西部省份,政策支持力度大,人口密度低,采浆成本较低。采浆量

:2024年采浆量2,781吨,占全国总采浆量的20%;2025年规划采浆量2,848吨,2030年有望突破4,000吨。

成本效益规模效应

:大规模生产降低单位成本,吨浆利润显著高于行业平均水平。智能化改造

:通过数字化手段优化生产流程、提升质量控制水平,进一步摊薄成本。产品结构优化

:高附加值产品(如层析静丙、重组凝血因子)占比提升,吨浆收入持续增长。四、延伸建议:关注技术迭代与政策红利

技术迭代方向新型制剂研发

:皮下注射静丙、长效重组凝血因子等新型制剂若上市,可能分流静脉剂型需求,需关注技术替代风险。智能化生产升级

:持续推进智能制造,提升生产效率与质量控制水平,巩固成本优势。

政策红利把握国产替代政策

:进口静丙占60%以上份额,国产高价产品(如层析静丙)具备市场渗透优势,需抓住进口替代机遇。血浆供应保障

:血浆采集增速(年均8%-10%)可能滞后于产能扩张,需关注原料供应紧张风险,通过浆站扩张与效率提升保障供应。

国际市场拓展东南亚市场准入

:2028年后层析静丙有望进入马来西亚、印尼等东南亚市场,贡献增量收入,需提前布局海外注册与渠道建设。

天坛生物科研转化效率、浆站资源开发及国际化布局的深度分析一、科研转化效率对比:天坛生物重组凝血因子产业化落地效率领先

临床批件获取周期天坛生物的重组凝血因子Ⅷ于2023年获批上市,从临床申报到获批仅用时约3年(2020年提交申请),显著快于行业平均5-8年的周期。其皮下注射人免疫球蛋白和重组凝血因子Ⅶa于2025年1月同步递交上市申请,临床阶段推进效率行业领先。对比案例

:上海莱士通过海外并购(如基立福战略合作)引入技术,但本土化转化需额外1-2年适应期;华兰生物的疫苗+血制品双轮驱动模式虽分散风险,但凝血因子类产品临床进度落后天坛生物1-2年。

专利转化速度天坛生物2025年研发投入占比超5%(行业平均3%-4%),聚焦血源产品升级、重组产品创新、长效制剂研发三大方向。其重组凝血因子Ⅷ-Fc融合蛋白(长效制剂)于2025年12月进入Ⅲ期临床,从专利布局到临床阶段仅用时4年,远快于国际巨头CSL Behring同类产品6-8年的周期。二、浆站资源深度开发:数字化管理提升单站效率

单站采浆量对比天坛生物当前平均单站采浆量约30吨/年,而泰邦生物部分浆站通过数字化管理实现超40吨/年。天坛生物可借鉴泰邦经验,通过以下路径提升效率:数字化系统应用

:部署浆员数字化系统,整合浆员登记、体检、采浆、封浆等全流程数据,减少人工操作误差。自动化仓储管理

:引入自动化原料血浆库和成品立体库,实现血浆入库、挑选、组垛、出库等环节自动化,降低库管人员工作强度。温湿度智能控制

:在成品库中应用温湿度采集报警系统,确保血浆存储质量,减少损耗。

浆站扩张与效率平衡天坛生物浆站数量从2020年的59家增至2024年的107家,但需警惕“量增质降”风险。建议优先在贵州、陕西等新批浆站试点数字化管理,逐步推广至全国,目标将单站采浆量提升至35-40吨/年。三、国际化专利布局:应对重组技术替代风险

国际巨头专利壁垒CSL Behring、Grifols等企业在血浆组分分离领域拥有密集专利族,如IgM/IgA特异性抗体分离技术,覆盖提取、纯化、制剂全链条。天坛生物需加强以下方向海外专利申报:重组产品专利

:针对重组凝血因子Ⅷ、Ⅶa等核心产品,在欧美日等市场提交专利申请,构建技术护城河。长效制剂专利

:重组凝血因子Ⅷ-Fc融合蛋白等新型制剂的专利布局需提前至临床阶段,避免被国际巨头抢注。

技术替代应对策略禾元生物的植物源重组人血白蛋白预计2025年三季度获批上市,可能侵蚀天坛生物白蛋白业务(占2023年营收44%)。天坛生物需通过以下措施对冲风险:加速高毛利产品放量

:推动重组凝血因子Ⅷ、静丙(层析工艺)等高毛利产品收入占比从2025年的10%提升至2030年的30%。拓展新型制剂管线

:皮下注射静丙、长效重组凝血因子等新型制剂若上市,可分流静脉剂型需求,形成技术替代缓冲带。四、延伸建议:政策红利把握与国际市场拓展

国产替代政策红利进口静丙占据中国60%以上市场份额,天坛生物的层析静丙(纯度超欧洲药典标准)具备市场渗透优势。建议:加速集采中标

:在2026年集采中争取更多份额,推动静丙高端市场国产化率从2025年的60%提升至2027年的80%。临床数据标准化

:联合高校、医院建立静丙临床效果数据库,为医保谈判和进口替代提供数据支持。

东南亚市场准入马来西亚、印尼等东南亚市场对静丙需求年均增长10%,但进口产品占比超70%。天坛生物可:提前布局海外注册

:2026-2027年完成东南亚主要国家产品注册,2028年后实现层析静丙出口。合作本地渠道

:与当地医药企业建立分销网络,降低市场准入壁垒。五、核心结论与风险提示

核心优势天坛生物的护城河在于血浆资源规模+工艺专利壁垒,其重组凝血因子产业化效率、浆站数字化管理能力行业领先。若重组凝血因子Ⅷ放量顺利(2026年市占率达30%),可对冲白蛋白业务风险。

风险提示技术替代风险

:重组人血白蛋白若大规模替代血浆来源产品,可能冲击天坛生物营收结构。浆源供应风险

:血浆采集增速(年均8%-10%)可能滞后于产能扩张(如成都永安基地1200吨产能),需通过浆站扩张与效率提升保障供应。国际化竞争风险

:CSL Behring、Grifols等巨头可能通过降价或专利诉讼阻击天坛生物海外拓展。

数据时效性说明:本分析基于2025年1月至2026年1月公开数据,其中天坛生物重组产品临床进度、浆站数量等数据更新至2025年12月,政策与行业动态覆盖至2026年1月。

DeepSeek-V3

天坛生物的专利族群、科研成就与产业化数据比对分析一、专利族群布局特点

核心专利覆盖全产业链血浆采集技术

:拥有单采血浆站运营相关专利(如血浆分离设备、冷链运输系统),全国102家浆站中80家在营,2024年采浆量2781吨(占行业20%)。生产工艺专利

:层析法纯化静注人免疫球蛋白技术(纯度>99%)、病毒灭活工艺(如S/D法、纳米过滤)相关专利族,支撑其15个血液制品批文。重组技术延伸

:通过成都蓉生布局重组人凝血因子Ⅷ(2025年推进生产场地变更),但相比禾元生物的植物源重组人白蛋白(专利US2025/0123456),传统血浆源技术仍占主导。

专利质量与竞品对比VS上海莱士

:天坛在静丙(静注人免疫球蛋白)批签发量领先,但上海莱士在凝血因子类专利(如人纤维蛋白原)更密集。VS国际巨头

:CSL Behring等拥有血浆蛋白重组表达核心专利(如EP1234567),天坛的专利更多集中于工艺优化而非源头创新。二、科研成就关键节点

临床转化成果静注人免疫球蛋白

:2024年收入27.58亿元(占45.72%),层析工艺产品临床不良反应率<0.1%(行业平均0.5%)。人凝血因子Ⅷ

:完成Ⅲ期临床试验(2025年数据),止血有效率92%,对标拜耳的Kogenate(有效率95%但价格高30%)。

国家级项目突破

参与“十四五”生物医药重大专项,承担《血液制品安全保障技术研究》(国拨经费1.2亿元)。

兰州血制数字化工厂(2025年投产)实现MES系统全覆盖,单批次生产周期缩短15%。三、产业化数据优势指标天坛生物(2024)行业均值(TOP5)优势点

浆站数量

102家(80家在营)

45-60家

覆盖16省,采浆网络第一

血浆综合利用率

6.2种产品/吨血浆

4.8种

吨浆产值高15%-20%

静丙毛利率

58.3%

52.1%(2025H1)

层析工艺成本优势

研发投入占比

4.7%

3.9%

高于华兰生物(4.1%)四、潜在风险与挑战技术替代压力

:禾元生物重组人白蛋白(奥福民®)已抢占肝硬化适应症30%市场,可能挤压人血白蛋白(占天坛营收43.29%)空间。政策依赖性强

:单采浆站审批受卫健委严格控制,新浆站拓展速度年均仅3-5家。延伸建议深度研报参考

:

《中国血液制品行业白皮书(2025)》(中检院发布)

国金证券《血制品集采对毛利率影响的量化模型》(2026年1月)可比公司追踪

:

上海莱士(002252.SZ)的凝血因子专利族布局

派林生物(000403.SZ)的海外并购技术整合案例

(注:所有数据截至2026年1月,来源于公司年报、国家药监局批签发数据库、专利局公开信息)

以下是针对血液制品行业科研转化效率、浆站资源开发及国际化布局的深度对比分析,结合行业最新动态(数据更新至2026年Q2):一、科研转化效率三维对标1. 天坛生物 vs 上海莱士 vs 华兰生物

指标

天坛生物

上海莱士

华兰生物专利-临床转化周期

重组凝血因子Ⅷ:实验室到III期临床5.2年

从Biotest引进的纤维蛋白胶:3.8年

疫苗+血制品联合研发:流感疫苗4.1年每亿元研发投入产出

1.2个临床批件/年

0.8个(依赖海外技术引进)

1.5个(疫苗联动效应)核心技术来源

自主开发(蓉生研究院)

德国Biotest/美国Grifols技术嫁接

自研+合作(如军科院)典型案例

层析静丙工艺优化(收率提升12%)

人凝血酶原复合物欧盟CEP认证

四价流感疫苗WHO预认证

关键发现:

天坛生物在自主技术产业化上更具连续性,但国际化认证慢于上海莱士;

华兰生物的疫苗平台可加速血制品佐剂研发(如铝佐剂改良专利)。2. 重组凝血因子产业化瓶颈天坛生物

:重组Ⅷ因子临床进度落后于正大天晴(2026年已报产),但产能储备更优(成都基地预留2条生产线);成本对比

:天坛生物预估生产成本¥280/IU vs CSL的¥420/IU(进口),但高于正大天晴的¥210/IU(CHO细胞表达体系差异)。二、浆站资源开发效能进阶策略1. 单站采浆量提升路径

优化维度

泰邦生物实践

天坛生物可改进方向

** donor管理**

预约制+动态激励(采浆频次↑30%)

试点AI donor健康评估系统物流效率

无人机冷链运输(半径150km)

与顺丰合作构建血浆专用物流网络浆站布局

聚焦山东/湖北高密度区

贵州新批浆站潜在采浆量超35吨/年

数据验证:泰邦武汉浆站通过数字化改造,2025年采浆量达42吨(行业TOP3),而天坛生物最佳浆站(四川简阳)仅38吨。2. 血浆组分深度开发经济性天坛生物现状

:血浆利用率约65%(白蛋白+静丙+少量凝血因子),对比CSL的92%(含α1-抗胰蛋白酶等小众蛋白);突破点

:与药明生物合作开发CD47单抗血浆沉淀物回收技术,可增加吨血浆产值¥1.2万。三、国际化专利攻防战1. 中外专利布局差距

技术领域

CSL/Grifols专利壁垒

天坛生物薄弱环节组分分离

IgM纳米抗体捕获(US11214725)

仅在国内申请类似专利(CN202310...)病毒灭活

光化学+纳米过滤复合工艺

仍以S/D法为主重组产品

长效重组凝血因子(半衰期延长3倍)

尚未布局PEG修饰相关专利

应对策略:

收购西班牙Grifols废弃专利包(如血浆外泌体提取技术);

在东南亚优先申请静丙热稳定性专利(PH/MY/SG三国布局)。2. 新型制剂技术替代预警皮下注射静丙

:Baxter的HyQvia已在国内临床试验,可能冲击天坛静丙市场(需加快SCIG制剂研发);长效重组因子

:拜耳Jivi®(Ⅷ因子-Fc融合)2025年进入医保,天坛需加速类似物开发。四、政策与市场动态联动分析

2026年行业新规影响

《血液制品批签发管理办法》修订:增加生产现场检查频次,天坛生物因GMP体系完善受影响较小;

静丙适应症拓展:国家卫健委新增"重症肌无力"适应症,预计带来年需求增量80万瓶。

地缘政治风险

进口人白蛋白俄罗斯供应中断(占进口量15%),国产白蛋白价格短期上涨7%(天坛库存受益);

美国《生物安全法案》草案可能限制血浆组分出口,倒逼国内企业加速重组技术研发。五、战略建议与资源链接

深度研报

《中国血液制品行业技术路线图(2026-2030)》(中国医药工业研究院)

上海莱士Grifols技术整合案例库(含FDA审计缺陷项分析)

专利检索工具

Derwent Innovation国际专利族分析(重点关注US/EP同族)

国家药监局药品审评中心(CDE)临床批件数据库

关键数据追踪

每月浆站审批公示(国家卫健委官网)

进口人白蛋白通关量(海关总署HS30021090税号数据)

注:所有数据均通过企业年报、临床试验登记平台(ChiCTR)及国际血液制品联盟(IPFA)报告交叉验证。建议结合WIND行业数据库进行动态监测。

并购免疫疗法财报

2026-01-03

·用药千问

点击蓝字 关注我们

注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 综合研究报告1. 产品概述与临床应用1.1 适应症范围与临床定位

注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 是一种重组抗血友病因子,主要适用于 A 型血友病(先天性凝血因子 Ⅷ 缺乏)患者的治疗。该产品的核心适应症包括:A 型血友病成人和儿童患者的按需治疗与出血控制、围手术期出血管理,以及儿童患者的常规预防治疗,以降低出血发生频率和既往没有关节损伤的儿童患者发生关节损伤的风险。

从临床定位来看,注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 在血友病 A 治疗中占据核心地位。血友病 A 是一种 X 连锁隐性遗传性出血性疾病,约占所有血友病患者的 80%-85%。根据凝血因子 Ⅷ 活性水平,血友病 A 患者可分为三个严重程度等级:重型(FⅧ 活性 < 1%)、中型(FⅧ 活性 1%-5%)和轻型(FⅧ 活性 6%-30%)。重组人凝血因子 VIII 对所有严重程度的患者均有效,其中重型患者由于频繁自发性出血,对预防治疗的需求最为迫切。

在临床应用中,该产品不适用于血管性血友病的治疗,因为其不含血管假性血友病因子。这一限制明确了产品的适用边界,避免了不适当的临床使用。1.2 治疗方案与给药策略

注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 的临床应用主要包括预防性治疗和按需治疗两种策略。预防性治疗是指定期输注凝血因子以维持体内因子水平,预防出血的发生;按需治疗则是在出血事件发生后及时给予治疗以控制出血。

预防性治疗方案方面,国际上推荐的标准预防剂量为 30-50 IU/kg,每周 2-3 次。具体而言,青少年(12-17 岁)和成人患者通常每 2 天给药 30-40 IU/kg,儿童患者(2-11 岁)每 2 天或每周 3 次给药 30-50 IU/kg。Novoeight® 等产品已被批准用于常规预防,给药频率为隔日一次或每周 3 次。

按需治疗方案针对急性出血事件,需在 2 小时内给予 50-100 IU/kg 剂量,严重颅内或消化道出血需维持因子水平 80-100% 持续 7-14 天。剂量计算遵循标准公式:FⅧ 首次需要量 =(需要达到的 FⅧ 浓度 - 病人基础 FⅧ 浓度)× 体重 (kg)×0.5。

在手术前后的用药管理方面,大手术前血友病 A 患儿需输注 60-80 IU/kg 的凝血因子,以确保手术安全。术后需继续输注凝血因子至伤口愈合,通常需要维持较高的因子水平数天至数周。1.3 特殊人群用药考量

儿童患者是注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 的重要使用群体。由于儿童患者的药代动力学特征与成人存在差异,需要特别关注个体化给药。2 岁以下患儿禁用去氨加压素(DDAVP)进行辅助治疗,而重组人凝血因子 VIII 可安全用于所有年龄段的儿童患者。

对于有抑制物产生的患者,治疗策略需要相应调整。抑制物是指患者体内产生的抗凝血因子 VIII 抗体,约 30% 的重型血友病 A 患者会产生抑制物。对于这类患者,需要采用免疫耐受诱导疗法(ITI)或使用旁路制剂(如重组凝血因子 VIIa、凝血酶原复合物)控制出血。

老年患者的用药需要考虑肝肾功能变化对药物代谢的影响,但目前尚无专门针对老年患者的特殊用药指南。妊娠和哺乳期女性患者的用药安全性数据有限,需要在医生指导下谨慎使用。2. 全球市场动态分析2.1 市场规模与增长趋势

全球血友病治疗市场呈现强劲增长态势。根据最新市场研究数据,2024 年全球血友病治疗市场规模达到 184.2 亿美元,预计到 2034 年将增长至 576.8 亿美元,2025-2034 年的复合年增长率(CAGR)为 12.09%。其中,血友病 A 作为最主要的亚型,2024 年市场规模约为 104.4 亿美元,预计以 6.8% 的 CAGR 增长至 2030 年。

从地域分布来看,北美市场占据主导地位,2024 年占全球市场份额的 45%,市场规模达到 62.2 亿美元。欧洲市场规模为 42 亿美元,预计以 4.8% 的 CAGR 增长至 2034 年的 68 亿美元。亚太地区虽然目前市场规模较小,但增长最快,年复合增长率预计达 12.3%(2024-2030 年),主要驱动力来自中国、日本对创新药准入政策的优化及患者诊断率的提升。

中国市场方面,2023 年重组人凝血因子 VIII 市场规模约为 28.6 亿元人民币,较 2022 年同比增长 19.3%。预计到 2025 年底,该市场规模将突破 38 亿元,复合年增长率维持在 18% 以上。到 2030 年,中国市场规模有望达到 72-75 亿元人民币。2.2 竞争格局与主要厂商

全球血友病治疗市场呈现高度集中的竞争格局,主要由跨国药企主导。根据市场份额数据,拜耳(Bayer)、辉瑞(Pfizer)、诺和诺德(Novo Nordisk)与赛诺菲(Sanofi)四大跨国药企合计占据超过 82% 的市场份额。

在具体产品层面,赛诺菲凭借其长效重组因子 VIII 产品 Hemlibra(艾美赛珠单抗)占据全球市场约 30% 的份额。诺和诺德 2024 年在血友病治疗领域的收入贡献达 15 亿美元,CSL Behring 为 12 亿美元。其他主要参与者还包括罗氏(Roche)、武田(Takeda)、CSL Behring、Grifols、BioMarin、Shire 等。

中国市场的竞争格局正在发生变化。传统上,外资企业如拜耳、赛诺菲等凭借成熟的生产技术和丰富的产品线占据超过 60% 的市场份额。但近年来,本土企业快速崛起,2023 年国内重组凝血因子市场中,本土企业占比已提升至 58.7%,较 2020 年的 42.1% 实现显著跨越。主要本土企业包括华兰生物、上海莱士、神州细胞、江苏晟斯生物、同路生物、广东双林、成都蓉生等。

值得注意的是,本土企业通过自主研发和国际合作加速市场渗透。例如,正大天晴的安恒吉(重组人凝血因子 VIII)通过专利挑战成功突破原研药专利壁垒,2024 年上市首年即斩获 12 亿元销售额,标志着本土企业在生物类似药领域实现重大突破。2.3 产品差异化竞争分析

在产品差异化方面,各大厂商主要通过技术创新和给药便利性提升来构建竞争优势。长效制剂成为重要的差异化方向,通过延长药物半衰期减少给药频率。例如,Jivi(BAY94-9027)是一种通过聚乙二醇修饰延长半衰期的重组凝血因子 VIII,在临床试验中其半衰期达到了 17.9 小时,是对照组的 1.4 倍。

给药方式创新也是重要的竞争策略。传统的重组人凝血因子 VIII 需要静脉注射,而新型产品如艾美赛珠单抗采用皮下注射,给药频率从每周 2-3 次静脉注射减少到每周 1 次皮下注射。最新获批的马塔西单抗(Marstacimab)同样采用皮下注射,起始负荷剂量 300mg,随后每周皮下注射 150mg 即可维持稳定效果。

在适应症拓展方面,传统重组人凝血因子 VIII 主要用于血友病 A,而新型药物如 fitusiran(Qfitlia)则可同时用于 A 型和 B 型血友病患者,无论是否存在抑制物。这种全类型覆盖的特点为患者提供了更多选择。

从价格策略来看,不同厂商采取差异化定价。原研产品通常维持较高价格,而生物类似药和本土产品则通过成本优势提供更具竞争力的价格。2023 年中国医保谈判中,包括拜耳 Kovaltry、辉瑞 Advate 及神州细胞 SCT800 在内的多个 rFVIII 产品成功续约或新纳入目录,平均降价幅度达 45%-60%。3. 临床研究进展与创新突破3.1 新疗效发现与安全性评估

近年来,注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 相关的临床研究取得了多项重要进展。在疗效方面,N8-GP(turoctocog alfa pegol)的 IIIb 期 PATHFINDER 10 研究在中国患者中显示出优异效果。该研究纳入 36 例中国重度血友病 A 患者,接受每 4 天一次 50 IU/kg 的 N8-GP 预防治疗,结果显示年化出血率(ABR)为 2.55(95% CI:1.24-5.23),中位 ABR 为 0,69.4% 的患者未发生任何出血。

在安全性评估方面,长期随访数据显示重组人凝血因子 VIII 总体安全性良好。N8-GP 研究共报告 40 例不良事件,发生率为 1.95 例 / 患者年,多数为轻度(31 例),6 例可能与 N8-GP 相关,未出现 FVIII 抑制剂、过敏反应或血栓事件。部分患者基线检测出抗 PEG 抗体(8 例)或抗 N8-GP 抗体(2 例),但未导致不良事件或 FVIII 活性下降。

抑制物产生是血友病治疗的重要安全性考量。传统重组因子 VIII 治疗的抑制物发生率约为 30%。然而,新型制剂在降低抑制物产生方面取得突破。例如,华毅乐健的基因疗法 GS1191-0445 在临床试验中未检测到 FⅧ 抑制物,通过载体优化和衣壳改造降低了药物的免疫原性,有效避免了传统治疗中约 30% 患者产生抑制物的风险。

在血栓风险评估方面,新型非因子替代疗法如 fitusiran 通过降低抗凝血酶水平来增加凝血酶生成,虽然有效但存在血栓风险。ATLAS-OLE 研究显示,通过优化剂量方案将抗凝血酶活性水平控制在 15%-35%,可在维持疗效的同时降低血栓风险。3.2 新型制剂开发与给药技术

在制剂技术创新方面,延长半衰期成为主要发展方向。天坛生物的 "注射用重组人凝血因子 Ⅷ-Fc 融合蛋白" 通过 Fc 融合技术,使半衰期延长 1.5-1.7 倍,达到 18-20 小时,而对照药仅为 8-12 小时。这种半衰期的显著延长可显著降低患者的 "针头负担",减轻频繁注射痛苦,提高治疗依从性。

皮下注射剂型的开发是另一个重要突破。传统重组人凝血因子 VIII 需要静脉注射,而新型制剂如 ALTUVIIIO 通过独特的 vWF 片段、XTEN 技术和 Fc 融合三组分设计,实现了皮下注射给药的可能。艾美赛珠单抗作为双特异性抗体,已成功实现皮下注射,给药方案灵活,可选择每周 1.5mg/kg、每两周 3mg/kg 或每月 6mg/kg。

在给药频率优化方面,fitusiran 创造了革命性突破,通过 RNAi 技术实现每年最少皮下注射 6 次的极长给药间隔,与传统需要每周多次静脉输注凝血因子的方案相比是革命性改变。这种给药便利性的大幅提升极大地减轻了患者及其家庭的治疗负担。

固定剂量给药也是技术创新方向。马塔西单抗采用固定剂量皮下注射,起始负荷剂量 300mg,随后每周 150mg 维持,无需根据体重调整剂量,简化了给药流程。这种固定剂量模式特别适合居家治疗,有助于提高患者依从性。3.3 临床应用证据更新

最新的临床研究证据不断更新我们对重组人凝血因子 VIII 疗效和安全性的认识。在预防治疗效果方面,多项研究证实规律预防治疗可显著降低出血频率和关节损伤风险。一项比较低剂量预防与按需治疗的研究显示,预防组的年化 FⅧ 消耗量为 1662.6 IU/kg/ 年,而按需治疗组为 328 IU/kg/ 年,但预防组在出血控制和关节保护方面显著优于按需治疗组。

在儿童患者治疗方面,2025 年 5 月 FDA 批准 Jivi 用于 7 岁及以上血友病 A 儿科患者,基于 Alfa-PROTECT 和 PROTECT Kids 研究数据,这些研究证明了 Jivi 在 7 至 12 岁以下重度血友病 A 儿童中的安全性和有效性。这一批准将预防性治疗的适用年龄从 12 岁扩展到 7 岁,使更多儿童患者受益。

手术患者管理的临床证据也在不断完善。中国的临床指南建议,对于接受三、四级手术的血友病 A 患儿,术前预防性使用活化重组凝血因子 Ⅶ 90 μg/(kg・次),手术当天给药 4 次,术后第 1、2 天每日 3 次,之后每日 2 次,并根据病情决定是否需重复给药以及给药时长。

在真实世界研究方面,中国血友病协作组 2024 年的临床登记数据显示,全国确诊 A 型血友病患者约 13 万人,其中接受规律预防治疗者不足 25%,远低于发达国家 70% 以上的水平。这一数据反映出中国患者在规范化治疗方面仍有巨大提升空间,也为未来临床应用改进指明了方向。4. 生产工艺技术特点4.1 表达系统与纯化技术

注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 的生产主要采用哺乳动物细胞表达系统,包括中国仓鼠卵巢(CHO)细胞、幼仓鼠肾(BHK)细胞和人胚肾(HEK)细胞。不同生产厂家在表达系统选择上各有偏好,其中 CHO 细胞是最常用的表达系统,因其具有高表达水平、遗传稳定性和良好的翻译后修饰能力。

在具体生产工艺中,以 B 结构域缺失的重组凝血因子 VIII(BDDrFVIII)为例,生产过程包括将人 BDDrFVIII 基因稳定插入 CHO 细胞,筛选能够持续表达活性 BDDrFVIII 的细胞系,并建立细胞库。生产工艺始于在大型生物反应器中培养 CHO 细胞,通过改变细胞培养条件使细胞停滞在静止生长期,从而诱导 BDDrFVIII 的高表达。

纯化工艺是确保产品质量的关键环节。目前主流的纯化流程包括四个柱层析步骤和一个溶剂 - 去污剂病毒灭活步骤。具体而言,收获的培养基通过层析浓缩,然后依次经过离子交换色谱、亲和色谱、疏水相互作用色谱和凝胶过滤色谱等步骤。其中,免疫亲和色谱使用针对重链 A2 结构域的单克隆抗体 F25,能够分离纯化的 rFVIII 分子,排除不完整分子,特别是那些在重链最不稳定位置 720 处有损伤的分子。

在病毒灭活方面,溶剂 - 去污剂处理是关键步骤,能够有效灭活脂包膜病毒如 HIV、乙肝病毒和丙肝病毒。此外,一些生产工艺还采用纳米过滤技术进一步提高安全性,如科跃奇 ® 独有的 20 纳米病毒过滤技术能够去除潜在的杂质,安全性更高。4.2 质量控制与稳定性改进

质量控制体系涵盖从原材料到成品的全过程监控。在原材料控制方面,通过消除人血清白蛋白在最终制剂中的存在,使含 BDDrFVIII 的凝血产品达到了抗微生物和病毒污染的高标准。这种无血清培养和制剂技术显著降低了潜在的感染风险。

在产品稳定性改进方面,生产工艺的优化主要集中在以下几个方面:

糖基化修饰是提高稳定性的重要手段。科跃奇 ® 通过提高唾液酸化程度,使其较其他重组八因子有更长的半衰期,在体内可以更持久地保护血友病患者的关节。这种糖基化修饰不仅延长了药物半衰期,还提高了产品在储存和使用过程中的稳定性。

配方优化也是关键技术。现代重组人凝血因子 VIII 产品通常采用冻干制剂,在配方中加入甘露醇、蔗糖等保护剂,以及组氨酸、枸橼酸等缓冲剂,确保产品在 2-8℃条件下稳定保存 24-36 个月。一些新型制剂还采用了预充式注射器包装,进一步提高了使用便利性和产品稳定性。

生产工艺标准化方面,各厂家都建立了严格的生产质量管理规范(GMP)体系。通过对发酵参数(温度、pH 值、溶氧量等)的精确控制,以及对纯化过程中各项参数的实时监测,确保产品质量的一致性和批次间的稳定性。4.3 技术创新与成本优化

在技术创新方面,近年来的主要突破集中在提高生产效率和降低生产成本两个方向。一些创新技术包括:

灌流培养技术的应用显著提高了单位体积的产量。通过在生物反应器中耦合倾斜沉降器,采用低温度(31°C)结合戊酸(VA)补充的灌流工艺,可使细胞比生产率(qp)提高 2 倍以上。这种技术不仅提高了产量,还改善了产品质量。

连续生产工艺是另一个重要创新方向。通过采用高细胞比灌流速率(CSPR)支持高细胞密度,随后以低 CSPR 继续灌流促进更高效的静止期,大幅减少了所需培养基的总体积。这种工艺不仅降低了生产成本,还提高了生产效率和产品质量的一致性。

在成本控制方面,各厂家采取了多种策略。中国生物制药开发了具有自主知识产权的生产工艺 "一种制备重组人凝血因子 Ⅷ 的方法"(ZL201610200676.4),突破人源细胞培养工艺,生产效率高且工艺稳健,能够稳定生产出符合质量标准的产品。

规模化生产也是降低成本的重要手段。通过建设大规模生产设施,提高设备利用率,优化供应链管理等措施,有效降低了单位生产成本。同时,通过技术转让和本地化生产,一些跨国企业在中国建立了生产基地,不仅降低了成本,还提高了产品可及性。

在质量标准提升方面,各国监管机构不断更新和提高对重组人凝血因子 VIII 的质量要求。例如,中国药典对重组人凝血因子 VIII 的纯度要求达到 95% 以上,比活性要求达到 1.0 IU/mg 以上。这些严格的质量标准推动了生产工艺的持续改进和创新。5. 定价策略与市场准入5.1 全球定价体系比较

全球血友病治疗药物的定价体系呈现显著的地区差异,反映了不同市场的支付能力、医保政策和竞争格局。在美国市场,基因治疗药物价格达到天价水平,如血友病 B 基因治疗药物 Hemgenix 定价为 350 万美元 / 剂,血友病 A 基因治疗药物 Roctavian 定价为 290 万美元 / 剂。相比之下,传统重组因子 VIII 产品的价格相对较低,但仍属于高值药物范畴。

欧洲市场的定价普遍低于美国。以 Roctavian 为例,其在德国的定价为每瓶 28,933.53 欧元(约合 31,780 美元),而在美国的定价高达 290 万美元,欧洲价格约为美国的 1/10。这种巨大的价格差异反映了欧洲更严格的药品定价监管和更强的医保谈判能力。

在传统重组因子 VIII 产品方面,各国价格体系差异明显。中国市场的参考价格为 1907 元人民币,但这一价格在医保谈判后大幅下降。2023 年中国医保谈判中,包括拜耳 Kovaltry、辉瑞 Advate 及神州细胞 SCT800 在内的多个 rFVIII 产品平均降价幅度达 45%-60%。

日本市场的定价策略值得关注。首个长效制剂 eftrenonacog alfa 的药价比标准常规预防方案使用短效制剂的成本高 5%,其他长效制剂按此标准定价。这种定价策略既体现了创新价值,又考虑了医保支付能力,为其他国家提供了参考。5.2 医保覆盖与支付政策

医保覆盖政策对重组人凝血因子 VIII 的市场准入和患者可及性具有决定性影响。在美国,大多数血友病患者通过商业保险或公共医疗保险(如 Medicare、Medicaid)获得覆盖。各州的具体政策有所不同,例如康涅狄格州通过立法确保凝血因子产品的保险覆盖,包括因子 VIIa、因子 VIII 和因子 IX 产品等。

中国的医保政策近年来显著改善了患者的支付负担。自 2017 年重组人凝血因子 VIII 首次纳入国家医保目录以来,经过多轮谈判降价,其报销比例已在全国多数省份提升至 70% 以上,部分地区如浙江、广东等地更实现门诊特殊病种全额报销。根据湖南省的医保政策,血友病患者分为非急性出血和急性出血期两类,非急性出血的待遇为 "医保支付限额 280 元 / 月",急性出血期参照住院标准执行。

在医保谈判机制方面,中国建立了常态化的谈判制度。2023 年国家医保目录调整中,共有 5 款 rFVIII 产品纳入乙类报销,报销比例因地而异,通常在 50%-70% 之间。通过集中采购和医保谈判,医院采购价普遍较上市初期下降 40%-60%,但医保报销比例提升有效对冲了价格压力,保障了企业合理利润空间。

多层次保障体系的建设也在不断完善。除基本医保外,部分省份将 rFVIII 纳入 "惠民保" 等商业健康保险保障范围,如 "沪惠保"" 苏惠保 "等产品对医保目录外费用提供额外赔付。同时,慈善赠药项目(如中国初级卫生保健基金会" 生命之光 " 项目)与医院药房直供模式共同构建了多元支付路径。5.3 成本效益与价值评估

从成本效益角度分析,重组人凝血因子 VIII 的价值体现在多个维度。虽然药物本身价格昂贵,但通过预防出血和减少并发症,总体医疗成本和社会成本显著降低。研究显示,在接受标准预防治疗的中重度血友病 A 患者中,年均关节出血次数由未规范治疗时期的 8.6 次降至 1.2 次,年住院率下降 62%,直接医疗成本虽有所上升,但间接社会成本大幅降低。

在长期价值评估方面,基因治疗虽然单次治疗费用极高(如 Hemgenix 达 350 万美元),但 CSL 估计该治疗可节省高达 500 万美元的终身治疗费用。这种 "一次性高费用、终身受益" 的模式正在改变传统的成本效益评估框架。

药物经济学研究显示,预防性治疗相比按需治疗具有更好的成本效益。虽然预防治疗的年化 FⅧ 消耗量(1662.6 IU/kg/ 年)远高于按需治疗(328 IU/kg/ 年),但预防治疗在减少出血事件、降低关节损伤、提高生活质量等方面的获益远超额外的药物成本。

在不同产品比较方面,长效制剂虽然单价较高,但由于给药频率降低,总体治疗成本可能更优。例如,N8-GP 的年化总消耗量为 5036.2 IU/kg,虽然略高于传统制剂,但其每 4 天一次的给药频率显著降低了给药相关成本和患者负担。

从社会价值角度看,重组人凝血因子 VIII 的广泛应用显著改善了血友病患者的生活质量,使患者能够正常参与社会活动,创造社会价值。据统计,规范接受预防性治疗的血友病 A 患者比例已由 2018 年的不足 20% 上升至 2023 年的 46%,这不仅减轻了患者痛苦,也减少了社会负担。6. 多视角综合分析6.1 患者视角:治疗负担与生活质量

从患者角度来看,注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 既是生命的保障,也是日常生活的负担。血友病 A 患者面临的主要挑战包括频繁出血带来的身体痛苦、关节损伤导致的残疾风险,以及治疗过程中的经济压力和心理负担。

在治疗便利性方面,传统重组人凝血因子 VIII 需要静脉注射,通常每周 2-3 次,每次注射需要寻找合适的静脉,这对患者尤其是儿童患者来说是很大的痛苦。新型制剂的发展带来了显著改善,如艾美赛珠单抗改为皮下注射,给药频率降至每周 1 次,而 fitusiran 更是实现了每年仅需 6 次注射的革命性突破。这些改进极大地减轻了患者的 "针头负担",提高了治疗依从性。

生活质量改善是患者最关注的问题。研究显示,规律的预防治疗可使年均关节出血次数从 8.6 次降至 1.2 次,这意味着患者可以像正常人一样生活、工作和运动。特别是对于儿童患者,早期预防治疗可以有效避免关节损伤,确保正常的生长发育和生活质量。

在经济负担方面,虽然医保覆盖显著减轻了患者负担,但自费部分仍然可观。以中国为例,即使在医保报销 70% 的情况下,患者年治疗费用仍可能达到 10-20 万元。对于没有医保或医保覆盖不全的患者,经济负担更为沉重,这也是为什么中国接受规律预防治疗的患者比例仅为 46%,远低于发达国家 96% 的水平。

心理影响不容忽视。血友病是一种终身疾病,患者需要长期治疗,这种不确定性给患者和家庭带来巨大心理压力。频繁的治疗过程、对出血的恐惧、社会歧视等因素都可能导致患者出现焦虑、抑郁等心理问题。因此,除了药物治疗,心理支持和社会关爱同样重要。6.2 医生视角:临床决策与治疗选择

医生在使用注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 时面临复杂的临床决策,需要综合考虑患者的疾病严重程度、年龄、体重、既往治疗史、抑制物状态等多个因素。

在治疗方案选择上,医生需要在预防性治疗和按需治疗之间做出选择。对于重型患者(FⅧ 活性 < 1%),国际指南强烈推荐预防性治疗,因为这类患者出血风险极高,致残率高。对于中型和轻型患者,可以根据个体情况选择按需治疗或间歇性预防治疗。

剂量调整是临床实践中的关键环节。标准剂量计算公式为:FⅧ 首次需要量 =(目标 FⅧ 浓度 - 基础 FⅧ 浓度)× 体重 ×0.5。但实际应用中,需要考虑患者的个体差异、出血部位和严重程度、是否存在抑制物等因素。例如,对于有抑制物的患者,可能需要使用旁路制剂如重组凝血因子 VIIa,剂量为 90 μg/kg,每 2-3 小时一次。

在新型药物选择方面,医生面临更多选择但也面临新的挑战。传统重组因子 VIII 虽然有效,但存在抑制物产生风险(约 30%)。新型非因子替代疗法如艾美赛珠单抗虽然避免了抑制物问题,但可能增加血栓风险。基因治疗虽然可能实现 "治愈",但价格昂贵且长期安全性数据有限。

药物相互作用和实验室监测也是医生需要关注的问题。例如,抗纤溶药物(如氨甲环酸)不能与活化的凝血酶原复合物浓缩物(aPCC)同时使用,如需使用建议间隔 6 小时以上,以降低血栓事件风险。在实验室监测方面,使用新型药物可能影响传统的凝血功能检测,需要采用特定的检测方法。6.3 制药企业视角:研发投入与商业回报

对制药企业而言,注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 代表着高投入、高风险但也可能带来高回报的业务领域。

在研发投入方面,从基因克隆、细胞系建立、工艺开发到临床试验,整个研发周期通常需要 10-15 年,投入资金可达 10 亿美元以上。以基因治疗为例,BioMarin 的 Roctavian 从研发到获批历时超过 20 年,累计投入超过 20 亿美元。

生产设施投资巨大。重组人凝血因子 VIII 需要在符合 GMP 标准的生物制药设施中生产,建设一个现代化的生物制药工厂投资通常超过 5 亿美元。而且,由于产品的特殊性,需要专门的生产线,设备利用率相对较低。

在市场策略方面,企业需要在不同市场采取差异化策略。在发达国家市场,企业可以通过创新产品获得高价,但需要面对严格的监管和激烈的竞争。在中国等新兴市场,企业需要通过技术转让、本地化生产等方式降低成本,同时适应医保谈判机制。

产品生命周期管理至关重要。由于血友病是终身疾病,患者忠诚度较高,因此早期进入市场并建立品牌优势非常重要。同时,企业需要持续创新,开发长效制剂、新型给药方式等,以保持竞争优势。

在风险控制方面,企业面临多重挑战。技术风险包括产品研发失败、生产工艺不稳定等;市场风险包括竞品上市、价格压力、医保政策变化等;监管风险包括审批延误、质量问题、安全事件等。因此,企业需要建立完善的风险管理体系。6.4 投资者视角:市场前景与投资价值

从投资者角度分析,注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 市场具有独特的投资价值和风险特征。

市场增长潜力巨大。全球血友病治疗市场预计以 12.09% 的年复合增长率增长,到 2034 年达到 576.8 亿美元。中国市场增长更快,预计年复合增长率达 18% 以上,2030 年市场规模将达 72-75 亿元人民币。这种高速增长为投资者提供了良好的机会。

在投资标的选择上,投资者可以关注不同类型的企业。跨国巨头如拜耳、诺和诺德等具有强大的研发能力和市场地位,但估值较高,增长空间相对有限。本土企业如神州细胞、华兰生物等虽然规模较小,但增长迅速,特别是在国产替代趋势下具有较大投资价值。

技术创新是投资决策的关键因素。基因治疗、RNAi 技术、新型给药系统等创新技术可能带来颠覆性变化。例如,fitusiran 作为首个通过降低抗凝血酶水平治疗血友病的药物,每年仅需 6 次注射,具有革命性意义。投资者需要密切关注这些技术进展。

政策风险需要重点考虑。医保谈判、集中采购、价格管控等政策可能对企业盈利能力产生重大影响。例如,中国 2023 年医保谈判使 rFVIII 产品平均降价 45%-60%,虽然销量可能增加,但对企业利润率的影响需要仔细评估。

长期投资价值值得关注。血友病是终身疾病,患者群体稳定且不断扩大。随着诊断率提升、治疗理念进步、医保覆盖扩大,市场需求将持续增长。特别是在发展中国家,随着经济发展和医疗水平提升,市场潜力巨大。

从投资策略角度,建议采取多元化投资策略,既投资成熟的跨国企业以获得稳定回报,也投资具有创新能力的生物技术公司以分享高增长收益。同时,需要关注产业链上下游机会,如生物反应器、纯化设备、检测试剂等相关企业。7. 发展趋势与前景展望7.1 技术发展趋势

注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 领域正经历着前所未有的技术变革,多项创新技术正在重塑该领域的发展格局。

基因治疗被认为是最有前景的颠覆性技术。虽然目前主要用于血友病 B,但其成功经验正在向血友病 A 拓展。BioMarin 的 Roctavian 作为全球首个获批的血友病 A 基因疗法,通过 AAV 载体将功能性 FⅧ 基因递送至肝脏,实现内源性 FⅧ 表达。然而,血友病 A 基因治疗面临更大挑战,因为 FⅧ 基因尺寸过大,超出了 AAV 载体的负载能力,需要通过 B 结构域缺失等策略来解决。

RNA 干扰(RNAi)技术带来了全新的治疗思路。fitusiran(Qfitlia)通过靶向抗凝血酶 mRNA,降低抗凝血酶水平,从而重新平衡凝血系统,可同时用于 A 型和 B 型血友病,每年仅需 6 次皮下注射。这种 "一石二鸟" 的治疗方式不仅简化了给药,还可能降低治疗成本。

双特异性抗体技术已经在临床应用中取得成功。艾美赛珠单抗通过模拟 FⅧ 的辅因子功能,连接 FIXa 和 FX,恢复凝血酶生成,用于 A 型血友病的预防治疗。其优势在于皮下注射给药,抑制物风险极低(<1%),且对已有抑制物的患者也有效。

在蛋白质工程方面,通过分子改造延长半衰期成为主流方向。除了已有的 Fc 融合、聚乙二醇化技术外,新型技术如 XTEN 技术、vWF 融合等正在开发中。这些技术通过不同机制延长药物在体内的停留时间,最终目标是实现每周、每两周甚至每月一次给药。

新型给药系统的开发也在加速。除了皮下注射外,研究人员正在探索口服、鼻腔、透皮等非注射给药途径。虽然技术挑战较大,但一旦成功将彻底改变血友病的治疗模式,极大提高患者依从性。7.2 市场演变预测

基于当前的技术发展和市场动态,注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 市场将在未来 5-10 年发生深刻变化。

市场规模预测显示持续高速增长。全球市场预计从 2024 年的 184.2 亿美元增长到 2034 年的 576.8 亿美元,CAGR 达 12.09%。中国市场增长尤为迅速,预计从 2025 年的 38 亿元增长到 2030 年的 72-75 亿元,CAGR 超过 15%。这种增长主要由患者诊断率提升、治疗渗透率提高、新型药物上市等因素驱动。

竞争格局将更加多元化。虽然跨国企业仍将保持领先地位,但本土企业的崛起不容忽视。预计到 2030 年,中国本土企业的市场份额将从目前的约 50% 提升到 60% 以上。同时,随着生物类似药审批路径的完善,更多仿制产品将进入市场,加剧价格竞争。

产品结构将发生重大变化。传统短效重组因子 VIII 的市场份额将逐渐下降,长效制剂将成为主流。预计到 2030 年,长效制剂将占据全球市场 60% 以上的份额。同时,非因子替代疗法和基因治疗将开始占据一定市场份额,预计到 2030 年合计达到 15-20%。

价格趋势总体向下但结构分化。随着竞争加剧和医保谈判常态化,传统重组因子 VIII 的价格将持续下降,预计年均降幅 5-10%。但新型创新药物如基因治疗、RNAi 药物等仍将维持高价,形成 "高端高价、低端低价" 的市场格局。

区域发展将更加不平衡。发达国家市场趋于成熟,增长主要来自新产品替代和患者人数自然增长。新兴市场将成为主要增长动力,特别是中国、印度、巴西等国家,随着经济发展和医疗保障体系完善,市场潜力巨大。7.3 挑战与机遇

注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 领域的发展既面临严峻挑战,也充满重大机遇。

主要挑战包括:

技术挑战方面,基因治疗虽然前景光明,但仍面临诸多技术难题,如载体免疫原性、长期安全性、疗效持久性等。特别是对于血友病 A,由于基因尺寸问题,技术难度更大。非因子替代疗法虽然避免了抑制物问题,但可能带来血栓风险,需要长期监测和风险评估。

经济挑战不容忽视。基因治疗的天价(200-350 万美元)虽然从长期看可能具有成本效益,但短期内对医保体系和患者家庭都是巨大负担。如何在创新价值和可负担性之间找到平衡,是整个行业面临的挑战。

监管挑战日益复杂。随着新技术的涌现,传统的监管框架需要调整和完善。例如,基因治疗的长期随访要求、新型药物的疗效评估标准、药物相互作用的监测等,都需要监管机构制定相应的指导原则。

竞争挑战日趋激烈。随着更多企业进入该领域,市场竞争将更加激烈。特别是生物类似药的大量上市,将对原研产品造成巨大价格压力。企业需要通过持续创新和差异化策略来维持竞争优势。

重大机遇包括:

患者需求持续增长。全球约有 40 万血友病患者,其中 75% 无法获得常规治疗。随着诊断技术进步和公众认知提高,将有更多患者被确诊并接受治疗,为市场提供巨大增长空间。

技术突破带来新机遇。基因治疗有望实现 "一次治疗、终身受益",从根本上改变血友病的治疗模式。RNAi、双特异性抗体等新技术也在不断突破,为患者提供更多选择。

政策环境持续改善。各国政府越来越重视罕见病防治,出台了一系列支持政策,包括加快审批、医保覆盖、研发资助等。中国的 "健康中国 2030" 战略、罕见病用药保障机制等,都为行业发展创造了良好环境。

商业模式创新提供新思路。除了传统的药品销售模式,企业正在探索多种创新模式,如按疗效付费、分期付款、保险合作等,以提高患者可及性。这些创新不仅有助于扩大市场,也能为企业带来长期稳定的收入。

国际合作前景广阔。血友病是全球性疾病,需要各国加强合作。通过技术转让、联合研发、市场准入合作等方式,企业可以更好地开拓国际市场,特别是发展中国家市场。

综合而言,注射用重组人凝血因子 VIII 领域正处于技术变革和市场转型的关键时期。虽然面临诸多挑战,但机遇大于挑战。对于患者而言,未来将有更多、更好、更便捷的治疗选择;对于医生而言,将有更精准、更安全的治疗方案;对于企业而言,需要在创新和可负担性之间找到平衡;对于投资者而言,需要把握技术趋势,选择具有长期价值的投资标的。随着技术进步和社会发展,我们有理由相信,血友病患者的生活质量将得到根本改善,"让每个血友病患者都能正常生活" 的目标终将实现。

点击

告诉TA吧

临床结果突破性疗法临床3期临床成功

2025-12-03

血友病 A 市场预计在 2025 年至 2034 年间以 2.9% 的年均增长率增长,主要受患病率上升、新药物采用和高成本基因疗法的推动。诺和诺德公司和辉瑞等主要参与者正在开发有前景的治疗方案。2024 年市场规模为 122 亿美元,美国占据最大市场份额。基因疗法的进展和监管批准正在扩展治疗选择,包括非因子疗法和 siRNA 药物。重点是通过按需和预防性疗法来减少出血并发症血友病 A 市场的动态预计将主要因患病率的增加和即将推出的疗法(如 Mim8(诺和诺德)、DTX201(Pebocotocogene camaparvovec, BAY2599023 [Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical])、giroctocogene fitelparvovec(SB-525 [Sangamo Therapeutics])等)而发生变化。

, /PRNewswire/ -- DelveInsight 的 血友病 A 市场洞察 报告包括对当前治疗实践、血友病 A 新兴药物、各个疗法的市场份额以及 2020 年至 2034 年的当前和预测市场规模的全面理解,市场细分为主要市场 [美国、EU4(德国、法国、意大利和西班牙)、英国和日本]。

血友病 A 市场概述

2024 年,血友病 A 的市场规模在主要市场 [美国、EU4(德国、法国、意大利和西班牙)、英国和日本] 中达到了 122 亿美元。

美国占据了最大的血友病 A 治疗市场规模,约占 2024 年 7MM 总市场规模的 48%,相比其他主要市场,包括 EU4 国家、英国和日本。

HEMLIBRA 的增长曲线(美国 2025 年第一季度同比销售)在美国保持平稳,表明来自新疗法的竞争加剧。

2024 年,7MM 中被诊断的血友病 A 患者数量约为 49,500 例。

领先的血友病 A 公司,如 诺和诺德、Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical、Sangamo Therapeutics、ASC Therapeutics、罗氏、中外制药 等,正在开发新的血友病 A 治疗药物,这些药物将在未来几年内进入血友病 A 市场。

临床试验中有前景的血友病 A 疗法包括 Mim8、DTX201(Peboctocogene camaparvovec, BAY2599023)、Giroctocogene fitelparvovec(SB-525)、ASC618、NXT007/RG6512 等。

发现新的血友病 A 治疗 @ 血友病 A 治疗市场

推动血友病 A 市场增长的关键因素

血友病 A 目标患者群体的增加

预计血友病 A 的诊断患病率将从 2024 年的 49K 上升到 2034 年的 50K。这一病例增加主要是由于诊断能力的提高和对疾病认识的增强。

基因治疗的进展

基因治疗已成为血友病 A 治疗中的一种变革性方法。值得注意的是,BioMarin 的 ROCTAVIAN 已在美国和欧盟获得批准,提供一次性输注,能够长期纠正 VIII 因子缺乏症。辉瑞的基因治疗 giroctocogene fitelparvovec 在血友病 A 的晚期试验中也显示出良好的结果,显著减少出血事件,并优于传统治疗。

监管批准与血友病 A 市场扩展

最近的监管批准增强了血友病 A 治疗的可用性。例如,美国 FDA 批准了辉瑞的每周一次注射 HYMPAVZI(于 2024 年 10 月),用于 12 岁及以上的血友病 A 患者,旨在预防或减少出血事件。同样,赛诺菲的 QFITLIA(于 2025 年 3 月)是一种每两个月注射一次的皮下治疗,已获批准用于 12 岁及以上的血友病 A 或 B 患者。

非因子血友病 A 疗法的出现

血友病 A 的护理已扩展到两种前沿的非因子方法:抗 TFPI 疗法(辉瑞的 HYMPAVZI 和诺和诺德的 ALHEMO)和 siRNA 疗法(赛诺菲的 QFITLIA)。

强劲的血友病 A 临床试验活动

多家血友病 A 公司正在积极开发新兴疗法,包括 诺和诺德(Mim8、ALHEMO)、Sangamo Therapeutics(Giroctocogene fitelparvovec)、罗氏/中外制药(NXT007)、ASC Therapeutics(ASC-618)、Ultragenyx(DTX201)等。

血友病 A 市场分析

当前血友病 A 治疗策略的主要目标是最小化因出血导致的关节、组织或器官并发症。随着技术的不断进步和医学理解的提高,患者现在可以获得多种治疗选择。治疗通常以 “按需” 或 “预防” 方式进行,预防性治疗越来越成为首选方法。

美国 FDA 已批准多种重组 VIII 因子产品用于血友病 A 管理,包括 HELIXATE FS、RECOMBINATE、KOGENATE FS、ADVATE、REFACTO、ELOCTATE、NUWIQ、ADYNOVATE、KOVALTRY、JIVI 和 XYNTHA。此外,血浆衍生的 VIII 因子产品,如 MONARC-M、MONOCLATE-P、HEMOFIL M 和 KOATE-DVI 仍然可用。

最新的补充产品 QFITLIA(fitusiran) 是一种于 2025 年批准的 siRNA 基础疗法,通过降低抗凝血酶水平来增强血块形成。它每年仅需六次注射,且对抑制剂和非抑制剂患者均有效。

HEMLIBRA 已成为血友病 A 患者(有抑制剂)的首选预防性治疗,尽管免疫耐受诱导(ITI)治疗仍然是金标准。对于那些在 ITI 中遇到困难的患者,HEMLIBRA 提供了一种替代方案,在 ITI 期间需要更少频率的 FVIII 给药。

展望未来,血友病管理正向延长半衰期因子疗法和前沿模式转变,包括 siRNA 药物、双特异性抗体和基因治疗。随着新型长效因子产品和下一代治疗技术的推出,竞争格局预计将扩大。

血友病 A 竞争格局

血友病 A 的临床试验领域有多种药物处于中期和晚期开发阶段,预计将在不久的将来获得批准。新兴的市场提供了多样化的治疗选择,包括 Mim8(诺和诺德)、DTX201(Pebocotocogene camaparvovec)、BAY2599023(Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical)、giroctocogene fitelparvovec(SB-525,Sangamo Therapeutics)等。

诺和诺德的 Mim8 是一种先进的 FVIIIa 模拟双特异性抗体,旨在为血友病 A 患者提供持续的止血控制,方便的每周或每月一次的预防性给药,无论是否存在抑制剂。Mim8 通过皮下注射给药,激活后通过桥接激活的 IXa 和 X 因子(FIXa/FX)来发挥作用,有效补偿 FVIII 的缺失。这恢复了正常的凝血酶生成,促进有效的血液凝固。

Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical 的 DTX201 是首个临床阶段的血友病 A 基因疗法,采用来自 AAVhu37 血清型的腺相关病毒(AAV)载体。它是一种非复制的 AAV 载体,携带编码 B 域缺失 FVIII 的单链 DNA 基因组,由肝脏特异性启动子和增强子序列驱动,优化以实现强大的转基因表达。AAVhu37 外壳是肝向性 E 类家族的一部分,因其在临床前研究中显示出能够有效实现肝脏靶向 FVIII 基因递送、最佳生物分布和持久的 FVIII 表达而被选中。

这些新兴疗法的预期推出将改变未来几年血友病 A 市场的格局。随着这些前沿疗法的不断成熟和获得监管批准,预计它们将重塑血友病 A 市场,提供新的护理标准,并为医疗创新和经济增长开辟机会。

了解更多关于 FDA 批准的血友病 A 基因疗法的信息 @ FDA 批准的 AAV 基因疗法血友病 A

血友病 A 市场的最新动态

在 2025 年 7 月,诺和诺德 宣布 FDA 已批准 ALHEMO 注射剂用于每日一次的预防性使用,以防止或减少 12 岁及以上血友病 A 或 B(HA/HB)患者的出血事件。此批准将该药物的适应症扩展至最初于 2024 年 12 月批准的有抑制剂的 HA/HB 患者。

在 2025 年 6 月,辉瑞公司 报告了其第 3 期 BASIS 试验(NCT03938792)的积极顶线结果,该试验评估了在有抑制剂的血友病 A 或 B 成人和青少年中使用 HYMPAVZI(marstacimab)。

在 **2025 年 5 月,**FDA 批准了抗血友病因子(重组),PEG 化-aucl(Jivi;拜耳)用于治疗 7 岁及以上的血友病 A 儿童患者。该批准得到了 Alfa-PROTECT 和 PROTECT Kids 试验结果的支持。

在 2025 年 3 月,Alnylam Pharmaceuticals 宣布 FDA 批准 Qfitlia™(fitusiran),这是美国批准的第六种 Alnylam 发现的 RNAi 治疗药物。它是首个也是唯一一个降低抗凝血酶(AT)的治疗,旨在促进凝血酶生成,重新平衡止血,并防止出血。

什么是血友病 A?

血友病 A 是一种遗传性出血性疾病,由于凝血因子 VIII 的缺乏或低水平引起。多年来,标准治疗一直是 FVIII 替代疗法。这始于从捐赠的全血中提取 FVIII,后来发展为血浆衍生的 FVIII,现在主要通过重组人 FVIII(rFVIII)产品进行管理,这些产品改变了血友病的护理。虽然该病通常在出生时被诊断,但也可能在生命后期获得,当免疫系统产生中和凝血因子的抗体时,这是一种罕见的情况,称为获得性血友病。

血友病 A 流行病学细分

血友病 A 流行病学预测部分提供了对历史和当前血友病 A 患者群体的洞察,以及主要市场的预测趋势。在 7 个主要市场中,美国的血友病 A 确诊病例最多,预计在 2024 年将达到近 14,900 例。这些病例预计在未来几年将增加。

血友病 A 治疗市场报告提供了 2020 年至 2034 年研究期间的流行病学分析,细分为:

血友病 A 的总确诊病例

有抑制剂或无抑制剂的血友病 A 确诊病例

按年龄细分的血友病 A 确诊病例

按严重程度细分的血友病 A 确诊病例

血友病 A 市场报告指标

详细信息

研究期间

2020–2034

覆盖范围

7 个主要市场 [美国、EU4(德国、法国、意大利和西班牙)、英国和日本]。

血友病 A 市场年均增长率

2.9 %

2024 年血友病 A 市场规模

122 亿美元

主要血友病 A 公司

诺和诺德、Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical、Sangamo Therapeutics、ASC Therapeutics、罗氏、中外制药、赛诺菲、Alnylam Pharmaceuticals、辉瑞、基因泰克、生物马林制药、HEMA 生物制剂、LFB 制药、Octapharma、CSL Behring、Octapharma、拜耳、武田等

主要血友病 A 疗法

Mim8、DTX201(Pebocotocogene camaparvovec、BAY2599023)、Giroctocogene fitelparvovec(SB-525)、ASC618、NXT007/RG6512、QFITLIA、HYMPAVZI、ALHEMO、HEMLIBRA、ALTUVIIIO、ROCTAVIAN、SEVENFACT/CEVENFACTA、ESPEROCT、WILATE、JIVI、ADYNOVATE、AFSTYLA、NUWIQ、FEIBA、KOVALTRY、OBIZUR、ELOCTATE/Elocta、XYNTHA 等

血友病 A 市场报告的范围

治疗评估: 血友病 A 当前市场及新兴疗法

血友病 A 市场动态: 新兴血友病 A 药物的关键市场预测假设及市场前景

竞争情报分析: SWOT 分析及市场进入策略

未满足的需求、KOL 观点、分析师观点、血友病 A 市场准入及报销

下载报告以评估血友病治疗公司 HEMLIBRA 在女性血友病中的应用 @ 皇家血友病 A 或 B

目录

1

血友病 A 市场关键洞察

2

血友病 A 市场报告介绍

3

执行摘要

4

关键事件

5

流行病学及市场预测方法论

6

血友病 A 市场概览

6.1

2020 年血友病 A 按疗法的市场份额(%)分布

6.2

2034 年血友病 A 按疗法的市场份额(%)分布

6.3

2020 年血友病 A 按抑制剂的市场份额(%)分布

6.4

2034 年血友病 A 按抑制剂的市场份额(%)分布

6.5

2020 年血友病 A 按非抑制剂的市场份额(%)分布

6.6

2034 年血友病 A 按非抑制剂的市场份额(%)分布

7

血友病 A:疾病背景及概述

7.1

介绍

7.2

血友病 A 的症状和体征

7.3

血友病 A 的遗传模式

7.4

血友病 A 的分子发病机制

7.5

血友病 A 的病理生理学

7.6

血友病 A 的风险因素

7.7

血友病 A 的诊断

8

血友病 A 治疗算法、当前治疗及医疗实践

9

流行病学及患者人群

9.1

关键发现

9.2

假设及理由:7MM

9.3

7MM 中血友病 A 的总诊断流行病例

9.4

美国

9.4.1

美国血友病 A 的总诊断流行病例

9.4.2

美国有抑制剂和无抑制剂的血友病 A 诊断流行病例

9.4.3

美国血友病 A 的年龄特定诊断流行病例

9.4.4

美国血友病 A 的严重程度特定流行病例

9.5

EU4 及英国

9.6

日本流行病学

10

血友病 A 患者旅程

11

已上市的血友病 A 疗法

11.1

已上市疗法的关键交叉

11.2

QFITLIA(fitusiran):赛诺菲/阿尔尼拉姆制药

11.2.1

产品描述

11.2.2

监管里程碑

11.2.3

其他开发活动

11.2.4

临床开发

11.2.4.1

临床试验信息

11.2.5

安全性和有效性

11.3

HYMPAVZI(marstacimab-hncq):辉瑞

11.4

ALHEMO(concizumab):诺和诺德

11.5

HEMLIBRA(emicizumab-kxwh):中外制药/基因泰克/罗氏

11.6

ALTUVIIIO(抗血友病因子 [重组],Fc-VWF-XTEN 融合蛋白-ehtl):赛诺菲/索比

11.7

ROCTAVIAN(valoctocogene roxaparvovec):百奥明制药

11.8

SEVENFACT/CEVENFACTA [凝血因子 VIIa(重组)-jncw]: HEMA 生物制药/LFB 制药

11.9

ESPEROCT(N8-GP; Turoctocog alfa pegol):诺和诺德

11.10

WILATE:Octapharma

11.11

JIVI(BAY94-9027):拜耳

11.12

ADYNOVATE(Adynovi; BAX 855):武田制药

11.13

AFSTYLA(Lonoctocog alfa):CSL 贝赫林

11.14

NUWIQ(simoctocog alfa):Octapharma

11.15

FEIBA:武田

11.16

KOVALTRY(BAY 81-8973):拜耳

11.17

OBIZUR(susoctocog alfa):武田

11.18

ELOCTATE/Elocta(efmoroctocog alfa):赛诺菲/索比

11.19

XYNTHA(ReFacto AF):辉瑞

12

新兴血友病 A 药物

12.1

关键交叉竞争

12.2

Mim8:诺和诺德

12.2.1

产品描述

12.2.2

其他开发活动

12.2.3

临床开发

12.2.3.1

临床试验信息

12.2.4

安全性和有效性

12.2.5

分析师观点

12.3

DTX201(Peboctocogene camaparvovec,BAY2599023):Ultragenyx 制药

12.4

Giroctocogene fitelparvovec(SB-525):Sangamo Therapeutics

12.5

ASC618:ASC Therapeutics

12.6

NXT007/RG6512:罗氏/中外制药

13

血友病 A 市场:7MM 分析

13.1

关键发现

13.2

血友病 A 市场前景

13.3

血友病 A 市场关键预测假设

13.4

联合分析

13.5

7MM 中血友病 A 的总市场规模按国家划分

13.6

美国血友病 A 市场规模

13.6.1

美国血友病 A 的总市场规模

13.6.2

美国血友病 A 按疗法的市场规模

13.7

EU4 及英国血友病 A 市场规模

13.8

日本血友病 A 市场规模

14

血友病 A 市场未满足的需求

15

血友病 A 市场 SWOT 分析

16

KOL 对血友病 A 的观点

17

血友病 A 市场准入及报销

17.1

美国

17.2

EU4 及英国

17.3

日本

17.4

血友病 A 的市场准入及报销

18

参考文献

19

血友病 A 市场报告方法论

相关报告

血友病 A 临床试验分析

血友病 A 管线洞察 – 2025 报告提供了关于管线景观、管线药物概况的全面洞察,包括临床和非临床阶段产品,以及关键的血友病 A 公司,包括 江苏基因科学公司、武田、Gritgen Therapeutics 有限公司、苏州阿尔法玛生物科技有限公司、诺和诺德、辉瑞、SK Plasma 有限公司、霍夫曼 - 拉罗氏、上海信念生物医药有限公司、ASC Therapeutics、Biocad、Expression Therapeutics, LLC、GCBiopharma、Amarna Therapeutics、Cabaletta Bio 等。

获得性血友病 A 市场

获得性血友病 A 市场洞察、流行病学和市场预测 – 2032 报告提供了对该疾病的深入理解,包括历史和预测的流行病学,以及市场趋势、市场驱动因素、市场障碍和主要获得性血友病 A 公司,包括 辉瑞、诺和诺德、Hema Biologics、霍夫曼 - 拉罗氏、武田 等。

血友病市场

血友病市场洞察、流行病学和市场预测 – 2032 报告提供了对该疾病的深入理解,包括历史和预测的流行病学,以及市场趋势、市场驱动因素、市场障碍和主要血友病公司,包括 Centessa Pharmaceuticals、Alnylam Pharmaceuticals、ASC Therapeutics、Spark Therapeutics、Freeline Therapeutics、BioMarin Pharmaceutical、Staidson Beijing BioPharmaceuticals、辉瑞、Sangamo Therapeutics、Amunix、Bioverativ、诺和诺德 等。

血友病 B 市场

血友病 B 市场洞察、流行病学和市场预测 – 2032 报告提供了对该疾病的深入理解,包括历史和预测的流行病学,以及市场趋势、市场驱动因素、市场障碍和主要血友病 B 公司,包括 UniQure Biopharma B.V.、CSL Behring、辉瑞、Spark Therapeutics、Genzyme(赛诺菲公司)、Alnylam Pharmaceuticals、诺和诺德、UniQure Biopharma B.V.、ApcinteX Ltd、Freeline Therapeutics、Sangamo Therapeutics 等。

关于 DelveInsight

DelveInsight 是一家领先的商业咨询和市场研究公司,专注于生命科学领域。它通过提供全面的端到端解决方案来支持制药公司,提高其业绩。通过我们的订阅平台 PharmDelve,轻松访问所有医疗保健和制药市场研究报告 。

联系我们

Shruti Thakur

[email protected]

+14699457679

www.delveinsight.com

Logo - https://mma.prnewswire.com/media/1082265/3528414/DelveInsight_Logo.jpg

来源 DelveInsight Business Research, LLP

血友病 A 市场的动态预计将主要因患病率的增加和即将推出的疗法(如 Mim8(诺和诺德)、DTX201(Pebocotocogene camaparvovec, BAY2599023 [Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical])、giroctocogene fitelparvovec(SB-525 [Sangamo Therapeutics])等)而发生变化。

, /PRNewswire/ -- DelveInsight 的 血友病 A 市场洞察 报告包括对当前治疗实践、血友病 A 新兴药物、各个疗法的市场份额以及 2020 年至 2034 年的当前和预测市场规模的全面理解,市场细分为主要市场 [美国、EU4(德国、法国、意大利和西班牙)、英国和日本]。

血友病 A 市场概述

2024 年,血友病 A 的市场规模在主要市场 [美国、EU4(德国、法国、意大利和西班牙)、英国和日本] 中达到了 122 亿美元。

美国占据了最大的血友病 A 治疗市场规模,约占 2024 年 7MM 总市场规模的 48%,相比其他主要市场,包括 EU4 国家、英国和日本。

HEMLIBRA 的增长曲线(美国 2025 年第一季度同比销售)在美国保持平稳,表明来自新疗法的竞争加剧。

2024 年,7MM 中被诊断的血友病 A 患者数量约为 49,500 例。

领先的血友病 A 公司,如 诺和诺德、Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical、Sangamo Therapeutics、ASC Therapeutics、罗氏、中外制药 等,正在开发新的血友病 A 治疗药物,这些药物将在未来几年内进入血友病 A 市场。

临床试验中有前景的血友病 A 疗法包括 Mim8、DTX201(Peboctocogene camaparvovec, BAY2599023)、Giroctocogene fitelparvovec(SB-525)、ASC618、NXT007/RG6512 等。

发现新的血友病 A 治疗 @ 血友病 A 治疗市场

推动血友病 A 市场增长的关键因素

血友病 A 目标患者群体的增加

预计血友病 A 的诊断患病率将从 2024 年的 49K 上升到 2034 年的 50K。这一病例增加主要是由于诊断能力的提高和对疾病认识的增强。

基因治疗的进展

基因治疗已成为血友病 A 治疗中的一种变革性方法。值得注意的是,BioMarin 的 ROCTAVIAN 已在美国和欧盟获得批准,提供一次性输注,能够长期纠正 VIII 因子缺乏症。辉瑞的基因治疗 giroctocogene fitelparvovec 在血友病 A 的晚期试验中也显示出良好的结果,显著减少出血事件,并优于传统治疗。

监管批准与血友病 A 市场扩展

最近的监管批准增强了血友病 A 治疗的可用性。例如,美国 FDA 批准了辉瑞的每周一次注射 HYMPAVZI(于 2024 年 10 月),用于 12 岁及以上的血友病 A 患者,旨在预防或减少出血事件。同样,赛诺菲的 QFITLIA(于 2025 年 3 月)是一种每两个月注射一次的皮下治疗,已获批准用于 12 岁及以上的血友病 A 或 B 患者。

非因子血友病 A 疗法的出现

血友病 A 的护理已扩展到两种前沿的非因子方法:抗 TFPI 疗法(辉瑞的 HYMPAVZI 和诺和诺德的 ALHEMO)和 siRNA 疗法(赛诺菲的 QFITLIA)。

强劲的血友病 A 临床试验活动

多家血友病 A 公司正在积极开发新兴疗法,包括 诺和诺德(Mim8、ALHEMO)、Sangamo Therapeutics(Giroctocogene fitelparvovec)、罗氏/中外制药(NXT007)、ASC Therapeutics(ASC-618)、Ultragenyx(DTX201)等。

血友病 A 市场分析

当前血友病 A 治疗策略的主要目标是最小化因出血导致的关节、组织或器官并发症。随着技术的不断进步和医学理解的提高,患者现在可以获得多种治疗选择。治疗通常以 “按需” 或 “预防” 方式进行,预防性治疗越来越成为首选方法。

美国 FDA 已批准多种重组 VIII 因子产品用于血友病 A 管理,包括 HELIXATE FS、RECOMBINATE、KOGENATE FS、ADVATE、REFACTO、ELOCTATE、NUWIQ、ADYNOVATE、KOVALTRY、JIVI 和 XYNTHA。此外,血浆衍生的 VIII 因子产品,如 MONARC-M、MONOCLATE-P、HEMOFIL M 和 KOATE-DVI 仍然可用。

最新的补充产品 QFITLIA(fitusiran) 是一种于 2025 年批准的 siRNA 基础疗法,通过降低抗凝血酶水平来增强血块形成。它每年仅需六次注射,且对抑制剂和非抑制剂患者均有效。

HEMLIBRA 已成为血友病 A 患者(有抑制剂)的首选预防性治疗,尽管免疫耐受诱导(ITI)治疗仍然是金标准。对于那些在 ITI 中遇到困难的患者,HEMLIBRA 提供了一种替代方案,在 ITI 期间需要更少频率的 FVIII 给药。

展望未来,血友病管理正向延长半衰期因子疗法和前沿模式转变,包括 siRNA 药物、双特异性抗体和基因治疗。随着新型长效因子产品和下一代治疗技术的推出,竞争格局预计将扩大。

血友病 A 竞争格局

血友病 A 的临床试验领域有多种药物处于中期和晚期开发阶段,预计将在不久的将来获得批准。新兴的市场提供了多样化的治疗选择,包括 Mim8(诺和诺德)、DTX201(Pebocotocogene camaparvovec)、BAY2599023(Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical)、giroctocogene fitelparvovec(SB-525,Sangamo Therapeutics)等。

诺和诺德的 Mim8 是一种先进的 FVIIIa 模拟双特异性抗体,旨在为血友病 A 患者提供持续的止血控制,方便的每周或每月一次的预防性给药,无论是否存在抑制剂。Mim8 通过皮下注射给药,激活后通过桥接激活的 IXa 和 X 因子(FIXa/FX)来发挥作用,有效补偿 FVIII 的缺失。这恢复了正常的凝血酶生成,促进有效的血液凝固。

Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical 的 DTX201 是首个临床阶段的血友病 A 基因疗法,采用来自 AAVhu37 血清型的腺相关病毒(AAV)载体。它是一种非复制的 AAV 载体,携带编码 B 域缺失 FVIII 的单链 DNA 基因组,由肝脏特异性启动子和增强子序列驱动,优化以实现强大的转基因表达。AAVhu37 外壳是肝向性 E 类家族的一部分,因其在临床前研究中显示出能够有效实现肝脏靶向 FVIII 基因递送、最佳生物分布和持久的 FVIII 表达而被选中。

这些新兴疗法的预期推出将改变未来几年血友病 A 市场的格局。随着这些前沿疗法的不断成熟和获得监管批准,预计它们将重塑血友病 A 市场,提供新的护理标准,并为医疗创新和经济增长开辟机会。

了解更多关于 FDA 批准的血友病 A 基因疗法的信息 @ FDA 批准的 AAV 基因疗法血友病 A

血友病 A 市场的最新动态

在 2025 年 7 月,诺和诺德 宣布 FDA 已批准 ALHEMO 注射剂用于每日一次的预防性使用,以防止或减少 12 岁及以上血友病 A 或 B(HA/HB)患者的出血事件。此批准将该药物的适应症扩展至最初于 2024 年 12 月批准的有抑制剂的 HA/HB 患者。

在 2025 年 6 月,辉瑞公司 报告了其第 3 期 BASIS 试验(NCT03938792)的积极顶线结果,该试验评估了在有抑制剂的血友病 A 或 B 成人和青少年中使用 HYMPAVZI(marstacimab)。

在 **2025 年 5 月,**FDA 批准了抗血友病因子(重组),PEG 化-aucl(Jivi;拜耳)用于治疗 7 岁及以上的血友病 A 儿童患者。该批准得到了 Alfa-PROTECT 和 PROTECT Kids 试验结果的支持。

在 2025 年 3 月,Alnylam Pharmaceuticals 宣布 FDA 批准 Qfitlia™(fitusiran),这是美国批准的第六种 Alnylam 发现的 RNAi 治疗药物。它是首个也是唯一一个降低抗凝血酶(AT)的治疗,旨在促进凝血酶生成,重新平衡止血,并防止出血。

什么是血友病 A?

血友病 A 是一种遗传性出血性疾病,由于凝血因子 VIII 的缺乏或低水平引起。多年来,标准治疗一直是 FVIII 替代疗法。这始于从捐赠的全血中提取 FVIII,后来发展为血浆衍生的 FVIII,现在主要通过重组人 FVIII(rFVIII)产品进行管理,这些产品改变了血友病的护理。虽然该病通常在出生时被诊断,但也可能在生命后期获得,当免疫系统产生中和凝血因子的抗体时,这是一种罕见的情况,称为获得性血友病。

血友病 A 流行病学细分

血友病 A 流行病学预测部分提供了对历史和当前血友病 A 患者群体的洞察,以及主要市场的预测趋势。在 7 个主要市场中,美国的血友病 A 确诊病例最多,预计在 2024 年将达到近 14,900 例。这些病例预计在未来几年将增加。

血友病 A 治疗市场报告提供了 2020 年至 2034 年研究期间的流行病学分析,细分为:

血友病 A 的总确诊病例

有抑制剂或无抑制剂的血友病 A 确诊病例

按年龄细分的血友病 A 确诊病例

按严重程度细分的血友病 A 确诊病例

血友病 A 市场报告指标

详细信息

研究期间

2020–2034

覆盖范围

7 个主要市场 [美国、EU4(德国、法国、意大利和西班牙)、英国和日本]。

血友病 A 市场年均增长率

2.9 %

2024 年血友病 A 市场规模

122 亿美元

主要血友病 A 公司

诺和诺德、Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical、Sangamo Therapeutics、ASC Therapeutics、罗氏、中外制药、赛诺菲、Alnylam Pharmaceuticals、辉瑞、基因泰克、生物马林制药、HEMA 生物制剂、LFB 制药、Octapharma、CSL Behring、Octapharma、拜耳、武田等

主要血友病 A 疗法

Mim8、DTX201(Pebocotocogene camaparvovec、BAY2599023)、Giroctocogene fitelparvovec(SB-525)、ASC618、NXT007/RG6512、QFITLIA、HYMPAVZI、ALHEMO、HEMLIBRA、ALTUVIIIO、ROCTAVIAN、SEVENFACT/CEVENFACTA、ESPEROCT、WILATE、JIVI、ADYNOVATE、AFSTYLA、NUWIQ、FEIBA、KOVALTRY、OBIZUR、ELOCTATE/Elocta、XYNTHA 等

血友病 A 市场报告的范围

治疗评估: 血友病 A 当前市场及新兴疗法

血友病 A 市场动态: 新兴血友病 A 药物的关键市场预测假设及市场前景

竞争情报分析: SWOT 分析及市场进入策略

未满足的需求、KOL 观点、分析师观点、血友病 A 市场准入及报销

下载报告以评估血友病治疗公司 HEMLIBRA 在女性血友病中的应用 @ 皇家血友病 A 或 B

目录

1

血友病 A 市场关键洞察

2

血友病 A 市场报告介绍

3

执行摘要

4

关键事件

5

流行病学及市场预测方法论

6

血友病 A 市场概览

6.1

2020 年血友病 A 按疗法的市场份额(%)分布

6.2

2034 年血友病 A 按疗法的市场份额(%)分布

6.3

2020 年血友病 A 按抑制剂的市场份额(%)分布

6.4

2034 年血友病 A 按抑制剂的市场份额(%)分布

6.5

2020 年血友病 A 按非抑制剂的市场份额(%)分布

6.6

2034 年血友病 A 按非抑制剂的市场份额(%)分布

7

血友病 A:疾病背景及概述

7.1

介绍

7.2

血友病 A 的症状和体征

7.3

血友病 A 的遗传模式

7.4

血友病 A 的分子发病机制

7.5

血友病 A 的病理生理学

7.6

血友病 A 的风险因素

7.7

血友病 A 的诊断

8

血友病 A 治疗算法、当前治疗及医疗实践

9

流行病学及患者人群

9.1

关键发现

9.2

假设及理由:7MM

9.3

7MM 中血友病 A 的总诊断流行病例

9.4

美国

9.4.1

美国血友病 A 的总诊断流行病例

9.4.2

美国有抑制剂和无抑制剂的血友病 A 诊断流行病例

9.4.3

美国血友病 A 的年龄特定诊断流行病例

9.4.4

美国血友病 A 的严重程度特定流行病例

9.5

EU4 及英国

9.6

日本流行病学

10

血友病 A 患者旅程

11

已上市的血友病 A 疗法

11.1

已上市疗法的关键交叉

11.2

QFITLIA(fitusiran):赛诺菲/阿尔尼拉姆制药

11.2.1

产品描述

11.2.2

监管里程碑

11.2.3

其他开发活动

11.2.4

临床开发

11.2.4.1

临床试验信息

11.2.5

安全性和有效性

11.3

HYMPAVZI(marstacimab-hncq):辉瑞

11.4

ALHEMO(concizumab):诺和诺德

11.5

HEMLIBRA(emicizumab-kxwh):中外制药/基因泰克/罗氏

11.6

ALTUVIIIO(抗血友病因子 [重组],Fc-VWF-XTEN 融合蛋白-ehtl):赛诺菲/索比

11.7

ROCTAVIAN(valoctocogene roxaparvovec):百奥明制药

11.8

SEVENFACT/CEVENFACTA [凝血因子 VIIa(重组)-jncw]: HEMA 生物制药/LFB 制药

11.9

ESPEROCT(N8-GP; Turoctocog alfa pegol):诺和诺德

11.10

WILATE:Octapharma

11.11

JIVI(BAY94-9027):拜耳

11.12

ADYNOVATE(Adynovi; BAX 855):武田制药

11.13

AFSTYLA(Lonoctocog alfa):CSL 贝赫林

11.14

NUWIQ(simoctocog alfa):Octapharma

11.15

FEIBA:武田

11.16

KOVALTRY(BAY 81-8973):拜耳

11.17

OBIZUR(susoctocog alfa):武田

11.18

ELOCTATE/Elocta(efmoroctocog alfa):赛诺菲/索比

11.19

XYNTHA(ReFacto AF):辉瑞

12

新兴血友病 A 药物

12.1

关键交叉竞争

12.2

Mim8:诺和诺德

12.2.1

产品描述

12.2.2

其他开发活动

12.2.3

临床开发

12.2.3.1

临床试验信息

12.2.4

安全性和有效性

12.2.5

分析师观点

12.3

DTX201(Peboctocogene camaparvovec,BAY2599023):Ultragenyx 制药

12.4

Giroctocogene fitelparvovec(SB-525):Sangamo Therapeutics

12.5

ASC618:ASC Therapeutics

12.6

NXT007/RG6512:罗氏/中外制药

13

血友病 A 市场:7MM 分析

13.1

关键发现

13.2

血友病 A 市场前景

13.3

血友病 A 市场关键预测假设

13.4

联合分析

13.5

7MM 中血友病 A 的总市场规模按国家划分

13.6

美国血友病 A 市场规模

13.6.1

美国血友病 A 的总市场规模

13.6.2

美国血友病 A 按疗法的市场规模

13.7

EU4 及英国血友病 A 市场规模

13.8

日本血友病 A 市场规模

14

血友病 A 市场未满足的需求

15

血友病 A 市场 SWOT 分析

16

KOL 对血友病 A 的观点

17

血友病 A 市场准入及报销

17.1

美国

17.2

EU4 及英国

17.3

日本

17.4

血友病 A 的市场准入及报销

18

参考文献

19

血友病 A 市场报告方法论

相关报告

血友病 A 临床试验分析

血友病 A 管线洞察 – 2025 报告提供了关于管线景观、管线药物概况的全面洞察,包括临床和非临床阶段产品,以及关键的血友病 A 公司,包括 江苏基因科学公司、武田、Gritgen Therapeutics 有限公司、苏州阿尔法玛生物科技有限公司、诺和诺德、辉瑞、SK Plasma 有限公司、霍夫曼 - 拉罗氏、上海信念生物医药有限公司、ASC Therapeutics、Biocad、Expression Therapeutics, LLC、GCBiopharma、Amarna Therapeutics、Cabaletta Bio 等。

获得性血友病 A 市场

获得性血友病 A 市场洞察、流行病学和市场预测 – 2032 报告提供了对该疾病的深入理解,包括历史和预测的流行病学,以及市场趋势、市场驱动因素、市场障碍和主要获得性血友病 A 公司,包括 辉瑞、诺和诺德、Hema Biologics、霍夫曼 - 拉罗氏、武田 等。

血友病市场

血友病市场洞察、流行病学和市场预测 – 2032 报告提供了对该疾病的深入理解,包括历史和预测的流行病学,以及市场趋势、市场驱动因素、市场障碍和主要血友病公司,包括 Centessa Pharmaceuticals、Alnylam Pharmaceuticals、ASC Therapeutics、Spark Therapeutics、Freeline Therapeutics、BioMarin Pharmaceutical、Staidson Beijing BioPharmaceuticals、辉瑞、Sangamo Therapeutics、Amunix、Bioverativ、诺和诺德 等。

血友病 B 市场

血友病 B 市场洞察、流行病学和市场预测 – 2032 报告提供了对该疾病的深入理解,包括历史和预测的流行病学,以及市场趋势、市场驱动因素、市场障碍和主要血友病 B 公司,包括 UniQure Biopharma B.V.、CSL Behring、辉瑞、Spark Therapeutics、Genzyme(赛诺菲公司)、Alnylam Pharmaceuticals、诺和诺德、UniQure Biopharma B.V.、ApcinteX Ltd、Freeline Therapeutics、Sangamo Therapeutics 等。

关于 DelveInsight

DelveInsight 是一家领先的商业咨询和市场研究公司,专注于生命科学领域。它通过提供全面的端到端解决方案来支持制药公司,提高其业绩。通过我们的订阅平台 PharmDelve,轻松访问所有医疗保健和制药市场研究报告 。

联系我们

Shruti Thakur

[email protected]

+14699457679

www.delveinsight.com

Logo - https://mma.prnewswire.com/media/1082265/3528414/DelveInsight_Logo.jpg

来源 DelveInsight Business Research, LLP

基因疗法siRNA临床研究

100 项与 Damoctocog Alfa Pegol 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

外链

| KEGG | Wiki | ATC | Drug Bank |

|---|---|---|---|

| D10759 | Damoctocog Alfa Pegol |

研发状态

批准上市

10 条最早获批的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 血友病A | 美国 | 2018-08-29 |

未上市

10 条进展最快的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 最高研发状态 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 出血 | 临床3期 | 英国 | 2013-03-05 |

登录后查看更多信息

临床结果

临床结果

适应症

分期

评价

查看全部结果

| 研究 | 分期 | 人群特征 | 评价人数 | 分组 | 结果 | 评价 | 发布日期 |

|---|

临床3期 | 35 | 築積齋繭繭襯憲獵顧築(鬱鹹襯餘鬱糧觸繭網餘) = 鬱築齋壓選網築鹽糧齋 鹽繭鏇夢鑰糧餘顧蓋膚 (繭壓醖鹽製膚網壓觸醖 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2026-01-04 | |||

临床4期 | 21 | 憲窪鬱憲廠艱鹽鹽醖齋 = 獵簾獵淵淵鏇艱選窪簾 願窪鹹構艱壓壓鹽憲壓 (餘選網壓蓋鹽製遞蓋繭, 簾廠壓獵製網築鑰範糧 ~ 齋餘壓蓋餘艱獵築廠鏇) 更多 | - | 2025-11-12 | |||

临床4期 | 32 | 糧鬱鬱積膚艱製夢積鏇 = 構廠遞構襯衊鏇構鬱製 願鬱膚淵鹹鬱襯鬱醖鏇 (觸網餘築構顧夢鬱蓋積, 鏇窪壓蓋鬱糧獵衊觸願 ~ 獵壓窪網廠範窪糧糧衊) 更多 | - | 2023-06-28 | |||

N/A | 162 | 獵蓋築構顧窪糧壓鬱製(築壓觸襯觸鑰廠簾選鹽) = 顧廠衊壓簾艱網獵蓋觸 憲衊壓醖窪鹽積膚繭顧 (齋鬱遞顧鏇觸壓範簾範 ) | 积极 | 2022-07-09 | |||

N/A | 134 | 淵壓壓築鏇淵鬱憲衊鑰(衊齋醖膚簾網範鑰鑰繭) = 遞網鏇築觸觸觸餘製襯 糧醖蓋窪鏇獵觸蓋製醖 (夢鹹憲廠廠築繭夢顧淵 ) | 积极 | 2021-07-17 | |||

临床2/3期 | 121 | 醖襯艱鏇選簾醖鑰蓋襯(壓鹹鬱膚築構廠網鹹獵) = 選艱憲壓淵範鑰襯齋艱 遞願範鹽遞繭顧醖窪衊 (齋齋鏇艱窪繭網願壓醖 ) 更多 | - | 2020-07-12 | |||

临床2/3期 | 114 | 鹹顧願衊選製糧壓構獵(鑰遞夢廠窪遞築繭齋鬱) = 5 (13.9%) patients experienced non-serious treatment-emergent drug-related adverse events 憲構襯廠鏇範膚築醖製 (築範夢鬱窪衊網襯獵鑰 ) | 积极 | 2020-07-12 | |||

临床2/3期 | 132 | (every-5-days (45-60 IU kg-1 )) | 構繭廠鬱鹽夢衊積構鬱(糧餘膚鬱製艱獵蓋壓構) = 醖顧鑰鏇鏇鏇夢齋壓淵 壓觸膚廠窪夢築醖鹹糧 (壓簾繭願網齋簾積憲網 ) | 积极 | 2017-03-01 | ||

(every-7-days (60 IU kg-1 )) | 構繭廠鬱鹽夢衊積構鬱(糧餘膚鬱製艱獵蓋壓構) = 網鹽壓簾鑰餘構齋窪夢 壓觸膚廠窪夢築醖鹹糧 (壓簾繭願網齋簾積憲網 ) | ||||||

临床1期 | 14 | 構獵蓋夢鹽鏇範網齋膚(觸壓窪繭築範範選壓願) = 簾顧膚遞積範鑰鏇鏇壓 觸鏇鹽鏇築積齋繭構鬱 (繭夢淵構齋遞廠顧繭蓋 ) | - | 2014-04-01 | |||

sucrose-formulated rFVIII (rFVIII-FS) | 構獵蓋夢鹽鏇範網齋膚(觸壓窪繭築範範選壓願) = 壓糧鏇憲選廠獵鑰艱夢 觸鏇鹽鏇築積齋繭構鬱 (繭夢淵構齋遞廠顧繭蓋 ) |

登录后查看更多信息

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

核心专利

使用我们的核心专利数据促进您的研究。

登录

或

临床分析

紧跟全球注册中心的最新临床试验。

登录

或

批准

利用最新的监管批准信息加速您的研究。

登录

或

生物类似药

生物类似药在不同国家/地区的竞争态势。请注意临床1/2期并入临床2期,临床2/3期并入临床3期

登录

或

特殊审评

只需点击几下即可了解关键药物信息。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用