预约演示

更新于:2026-02-27

INXN-2001

更新于:2026-02-27

概要

基本信息

在研机构- |

权益机构- |

最高研发阶段终止临床2期 |

首次获批日期- |

最高研发阶段(中国)- |

特殊审评- |

登录后查看时间轴

关联

8

项与 INXN-2001 相关的临床试验NCT04006119

A Phase II Study of Ad-RTS-hIL-12 + Veledimex in Combination With Cemiplimab-rwlc (Libtayo®) in Subjects With Recurrent or Progressive Glioblastoma

This research study involves an investigational product: Ad-RTS-hIL-12 given with veledimex for production of human IL-12. IL-12 is a protein that can improve the body's natural response to disease by enhancing the ability of the immune system to kill tumor cells and may interfere with blood flow to the tumor.

Cemiplimab-rwlc (Libtayo) is an antibody (a kind of human protein) that is being tested to see if it will allow the body's immune system to work against glioblastoma tumors. Libtayo (cemiplimab-rwlc) is currently FDA approved in the United States for metastatic cutaneous cell carcinoma (CSCC), but is not approved in glioblastoma. Cemiplimab-rwlc may help your immune system detect and attack cancer cells. Ad-RTS-hIL-12 and veledimex will be given in combination with cemiplimab-rwlc to enhance the IL-12 mediated effect observed to date.

The main purpose of this study is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a single tumoral injection of Ad-RTS-hIL-12 given with oral veledimex in combination with cemiplimab-rwlc.

Cemiplimab-rwlc (Libtayo) is an antibody (a kind of human protein) that is being tested to see if it will allow the body's immune system to work against glioblastoma tumors. Libtayo (cemiplimab-rwlc) is currently FDA approved in the United States for metastatic cutaneous cell carcinoma (CSCC), but is not approved in glioblastoma. Cemiplimab-rwlc may help your immune system detect and attack cancer cells. Ad-RTS-hIL-12 and veledimex will be given in combination with cemiplimab-rwlc to enhance the IL-12 mediated effect observed to date.

The main purpose of this study is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a single tumoral injection of Ad-RTS-hIL-12 given with oral veledimex in combination with cemiplimab-rwlc.

开始日期2019-08-01 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT03679754

Protocol ATI001-102 Expansion Substudy: Evaluation of Ad-RTS-hIL-12 + Veledimex in Subjects With Recurrent or Progressive Glioblastoma

This research study involves an investigational product: Ad-RTS-hIL-12 given with veledimex for production of human IL-12. IL-12 is a protein that can improve the body's natural response to disease by enhancing the ability of the immune system to kill tumor cells and may interfere with blood flow to the tumor.

The main purpose of this study is to evaluate the safety and tolerability of a single intratumoral injection of Ad-RTS-hIL-12 given with oral veledimex.

The main purpose of this study is to evaluate the safety and tolerability of a single intratumoral injection of Ad-RTS-hIL-12 given with oral veledimex.

开始日期2018-09-05 |

申办/合作机构 |

NCT03636477

Protocol ATI001-102 Substudy: Evaluation of Ad-RTS-hIL-12 + Veledimex in Combination With Nivolumab in Subjects With Recurrent or Progressive Glioblastoma

This research study involves an investigational product: Ad-RTS-hIL-12 given with veledimex for production of human interleukin-12 (IL-12). IL-12 is a protein that can improve the body's natural response to disease by enhancing the ability of the immune system to kill tumor cells and may interfere with blood flow to the tumor.

Nivolumab is an antibody (a kind of human protein) that is being tested to see if it will allow the body's immune system to work against glioblastoma tumors. Opdivo (Nivolumab) is currently FDA approved in the United States for melanoma (a type of skin cancer), non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell cancer (a type of kidney cancer), Hodgkin's lymphoma but is not approved in glioblastoma. Nivolumab may help your immune system detect and attack cancer cells. Ad-RTS-hIL-12 and veledimex will be given in combination with Nivolumab to enhance the IL-12 mediated effect observed to date.

The main purpose of this substudy is to evaluate the safety and tolerability of a single tumoral injection of Ad-RTS-hIL-12 given with oral veledimex in combination with nivolumab.

Nivolumab is an antibody (a kind of human protein) that is being tested to see if it will allow the body's immune system to work against glioblastoma tumors. Opdivo (Nivolumab) is currently FDA approved in the United States for melanoma (a type of skin cancer), non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell cancer (a type of kidney cancer), Hodgkin's lymphoma but is not approved in glioblastoma. Nivolumab may help your immune system detect and attack cancer cells. Ad-RTS-hIL-12 and veledimex will be given in combination with Nivolumab to enhance the IL-12 mediated effect observed to date.

The main purpose of this substudy is to evaluate the safety and tolerability of a single tumoral injection of Ad-RTS-hIL-12 given with oral veledimex in combination with nivolumab.

开始日期2018-06-18 |

申办/合作机构 |

100 项与 INXN-2001 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 INXN-2001 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 INXN-2001 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

21

项与 INXN-2001 相关的文献(医药)2022-06-01·NEURO-ONCOLOGY1区 · 医学

Combined immunotherapy with controlled interleukin-12 gene therapy and immune checkpoint blockade in recurrent glioblastoma: An open-label, multi-institutional phase I trial

1区 · 医学

Article

作者: Truman, Kyla ; Cooper, Laurence ; Hadar, Nira ; Bi, Wenya Linda ; Gelb, Arnold B ; Peruzzi, Pierpaolo ; Tringali, Joseph ; Park, Grace ; Triggs, Dan ; Lukas, Rimas V ; Estupinan, Taylor ; Seften, Leah ; Wen, Patrick Y ; Chadha, Kamal ; Buck, Jill Y ; Reardon, David A ; Loewy, John ; Chiocca, E Antonio ; Grant, James ; Amidei, Christina ; Rao, Ganesh ; Miao, John ; Chen, Clark C ; Demars, Nathan

Abstract:

Background:

Veledimex (VDX)-regulatable interleukin-12 (IL-12) gene therapy in recurrent glioblastoma (rGBM) was reported to show tumor infiltration of CD8+ T cells, encouraging survival, but also up-regulation of immune checkpoint signaling, providing the rationale for a combination trial with immune checkpoint inhibition.

Methods:

An open-label, multi-institutional, dose-escalation phase I trial in rGBM subjects (NCT03636477) accrued 21 subjects in 3 dose-escalating cohorts: (1) neoadjuvant then ongoing nivolumab (1mg/kg) and VDX (10 mg) (n = 3); (2) neoadjuvant then ongoing nivolumab (3 mg/kg) and VDX (10 mg) (n = 3); and (3) neoadjuvant then ongoing nivolumab (3 mg/kg) and VDX (20 mg) (n = 15). Nivolumab was administered 7 (±3) days before resection of the rGBM followed by peritumoral injection of IL-12 gene therapy. VDX was administered 3 hours before and then for 14 days after surgery. Nivolumab was administered every two weeks after surgery.

Results:

Toxicities of the combination were comparable to IL-12 gene monotherapy and were predictable, dose-related, and reversible upon withholding doses of VDX and/or nivolumab. VDX plasma pharmacokinetics demonstrate a dose-response relationship with effective brain tumor tissue VDX penetration and production of IL-12. IL-12 levels in serum peaked in all subjects at about Day 3 after surgery. Tumor IFNγ increased in post-treatment biopsies. Median overall survival (mOS) for VDX 10 mg with nivolumab was 16.9 months and for all subjects was 9.8 months.

Conclusion:

The safety of this combination immunotherapy was established and has led to an ongoing phase II clinical trial of immune checkpoint blockade with controlled IL-12 gene therapy (NCT04006119).

2012-12-01·Oncoimmunology2区 · 医学

Chemoimmunotherapy for advanced gastrointestinal carcinomas: A successful combination of gene therapy and cyclophosphamide

2区 · 医学

ArticleOA

作者: Mariana Garcia ; Laura Alaniz ; Jorge B. Aquino ; Pablo Matar ; Manuel Gidekel ; Esteban Fiore ; Flavia Piccioni ; Juan Bayo ; Catalina Atorrasagasti ; Mariana Malvicini ; Guillermo Mazzolini

The combination of a single low dose of cyclophosphamide (Cy) with the adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of interleukin-12 (AdIL-12) might represent a successful therapy for experimental gastrointestinal tumors. This approach has been proven to revert immunosuppressive mechanisms elicited by cancer cells and to synergistically promote antitumor immunity. In addition, this therapeutic regimen has been shown to be more efficient in achieving complete tumor regressions in mice than the application of a metronomic schedule of Cy plus AdIL-12.

2011-05-01·Nan fang yi ke da xue xue bao = Journal of Southern Medical University

[Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells with adenovirus-mediated interleukin 12 gene transduction inhibits the growth of ovarian carcinoma cells both in vitro and in vivo].

Article

作者: Shi, Peng-fei ; Cheng, Jian-xin ; Zhao, Wen-hong ; Huang, Jun-yan

OBJECTIVE:

To study the inhibitory effect of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (UC-MSCs) infected by a adenoviral vector containing interleukin 12 (IL-12) gene on the proliferation of ovarian carcinoma SKOV3 in vitro and the growth of tumor explants in nude mice.

METHODS:

Cultured human UC-MSCs were infected with the recombinant adenovirus vector harboring IL-12 gene to establish the IL-12-expressing cell line AdIL-12-MSCs. Western blotting and RT-PCR were used to detect IL-12 expressions in AdIL-12-MSCs at the protein and mRNA levels, respectively. ELISA were used to detect IL-12 content in the supernatant of AdIL-12-MSCs, whose effect on the proliferation and apoptosis of ovarian carcinoma SKOV3 cells was evaluated with MTT assay and flow cytometry, respectively. In a nude mouse model bearing subcutaneous SKOV3 tumor explants, AdIL-12-MSCs were infused via the tail vein and the inhibitory effect on the tumor growth was observed.

RESULTS:

The exogenous IL-12 gene was successfully transduced into UC-MSCs by the recombinant adenovirus vector, resulting in efficient IL-12 expression in the cell at both the protein and mRNA levels. The supernatant of AdIL-12-MSCs significantly inhibited the proliferation of SKOV3 cells and induced cellular apoptosis in vitro as compared with UC-MSC supernatant. In the tumor-bearing nude mouse model, the transplantation of AdIL-12-MSCs significantly inhibited the growth of SKOV3 tumor explants (P<0.05).

CONCLUSION:

Human UC-MSCs with IL-12 gene transduction, which express IL-12 at protein and mRNA levels, can inhibit the proliferation and induce apoptosis of ovarian carcinoma SKOV3 cells in vitro, and suppress the growth of ovarian cancer explants in nude mice.

8

项与 INXN-2001 相关的新闻(医药)2024-11-07

摘要:大多数原发性脑肿瘤是胶质瘤,其中多形性胶质母细胞瘤(GBM)是成人中最常见恶性肿瘤。GBM的中位生存期为18至24个月,尽管进行了广泛的研究,它仍然是不可治愈的,因此迫切需要新的治疗方法。

目前的护理标准是手术、放疗和化疗的结合,但由于胶质瘤的侵袭性和高复发性,这些方法仍然无效。基因治疗是一种针对多种肿瘤类型(包括GBM)的研究性治疗策略。在基因治疗中,使用多种载体来传递设计用于不同抗肿瘤效果的基因。此外,在过去的几十年中,干细胞生物学为癌症治疗提供了一种新的方法。干细胞可以用作再生医学、治疗载体、药物靶向和免疫细胞的生成。基于干细胞的治疗允许针对性治疗,保护健康脑组织,并通过刺激免疫系统、传递前药、代谢基因甚至溶瘤病毒来建立长期的抗肿瘤反应。

本章从临床前和临床的角度描述了针对GBM的基因和基于细胞的治疗的最新发展和当前趋势,包括不同的基因治疗传递系统、分子靶标和干细胞治疗。

1.引言

已经识别出超过120种脑肿瘤类型,它们可以被划分为良性或恶性肿瘤,包括脑转移瘤。原发性脑肿瘤涵盖了广泛的肿瘤类型,对患者的临床影响广泛,例如可以外科治愈的毛细胞型星形细胞瘤,以及高度侵袭性和不可治愈的肿瘤,如多形性胶质母细胞瘤。大约29.7%的所有原发性肿瘤是恶性的。中枢神经系统(CNS)中最常见的肿瘤是胶质瘤。它们约占所有原发性脑肿瘤和其他CNS肿瘤的25.1%,以及恶性脑肿瘤的80.8%。多形性胶质母细胞瘤(GBM)是成人中最常见的恶性脑肿瘤。GBM具有高度的肿瘤间和肿瘤内异质性,其特征是无控制的细胞增殖,广泛的血管生成,微血管增殖和高度侵袭性特征。原发性恶性胶质瘤的当前标准治疗(SOC)包括最大安全手术切除,随后进行同步外部放射治疗和替莫唑胺(TMZ)化疗。尽管如此,GBM的中位生存期为18至24个月,尽管进行了广泛的临床和基础研究,它仍然是不可治愈的;因此迫切需要新的治疗方法。

神经肿瘤学专注于原发性和转移性脑肿瘤的治疗,其最大的挑战之一是找到能够真正穿透血脑屏障(BBB)到达肿瘤的治疗方法。由于肿瘤的侵袭性特征,手术切除很少能完全移除每个肿瘤细胞,而且由于化疗无法有效地到达大脑并达到治疗浓度,这些肿瘤会重新出现。BBB的存在在限制抗肿瘤药物传递方面起着关键作用。大脑毛细血管内皮细胞中的紧密连接限制了血液分子进入大脑。尽管BBB在肿瘤部位本身发生了改变,但内皮细胞仍然阻止药物进入大脑。已经研究了不同的治疗传递策略,试图克服这一挑战,但迄今为止临床成功有限。

基因治疗作为一种药物传递形式出现,其中遗传物质利用细胞机制来治疗疾病。有不同类型的载体可能传递治疗性核酸酸或基因治疗,即病毒载体、纳米颗粒(NP)和干细胞。在本节中,我们将回顾不同的载体,治疗胶质瘤的方法,以及它们当前使用的临床阶段。

2.病毒载体

2.1.腺病毒载体

自20世纪50年代以来,病毒在癌症治疗中的应用已经在临床前和临床上进行了测试。腺病毒(AdV)属于腺病毒科。它们于1953年从人类扁桃体中分离出来,并被用作分子生物学研究的重要工具,如剪接。腺病毒是有效的基因传递工具;它们以其大尺寸(直径80-110纳米),无包膜,以及它们的基因组是26-45 kb的线性双链DNA分子,在二十面体蛋白衣壳内;它相对稳定于物理和化学变化,使它们能够在体外存活。AdV对包括人类在内的多种脊椎动物都有感染性;有49种不同种类的腺病毒,可引起肺炎、支气管炎、胃肠感染等。这些病毒的主要优点是它们容易遗传操作,几乎可以在所有分裂和非分裂细胞类型中轻松转染,生长到高滴度,最小的生物安全风险,以及高转导效率。它们可以传递大约8 kb的转基因,以及在新一代辅助依赖载体中高达30 kb。然而,它们的主要缺点之一是它们产生的免疫反应。

腺病毒基因组包含控制病毒生命周期两个不同阶段的基因,即早期和晚期。早期基因参与宿主细胞的进入和基因组传递到细胞核以及病毒DNA的复制(E1至E4区域)。晚期基因指导与病毒结构部分相关的基因的转录/翻译(L1至L5区域)。已经建立了不同类型的Adv载体,用于基因治疗方法。第一代载体删除了E1a和E1b基因,并插入了多达3-4 kb的外源DNA,或删除E1和E3并插入5-6 kb的转基因序列,如治疗或报告基因。第一代载体的问题是对转导细胞的高免疫原性。为了克服第一代载体的一些限制,第二代腺病毒载体被生成,使用E1和E2或E1和E4基因的删除。尽管第二代Ad载体呈现降低的肝毒性和体内更大的稳定性,但它们仍然面临病毒免疫学挑战,构建更加复杂。最后一代腺病毒载体被称为无病毒或辅助病毒依赖性,其中整个病毒编码序列被移除,减少了免疫原性并增强了安全性。这些载体保留了基因组的末端部分,即DNA复制所需的ITRs序列,以及病毒的包装信号(Ψ)。

由于胶质瘤治疗的耐药性,使用病毒的基因治疗被视为一种有希望的方法。已经开发了不同的针对GBM治疗的病毒治疗方法,包括自杀基因治疗、免疫刺激性基因治疗和溶瘤病毒治疗。目前,有几个I期和II期临床试验正在检查Ad载体在不同类型的成人和儿童胶质瘤中的有效性。

自杀基因治疗是针对胶质瘤治疗在临床前和临床水平上研究的主要基因治疗方法之一。该方法基于传递自杀基因,这些基因可以将无毒的前药转化为活性有毒化合物,导致转导的肿瘤细胞死亡。这种方法对复制细胞是致命的,针对脑肿瘤细胞,而不一定损害正常、非分裂的脑细胞。腺病毒载体已被用于表达单纯疱疹病毒胸苷激酶(HSV-TK)的自杀基因治疗,随后进行更昔洛韦(GCV)治疗。HSV-TK磷酸化GCV,单磷酸化GCV进一步磷酸化以产生三磷酸-GCV(3P-GCV)。当细胞分裂时,3P-GCV被并入新的DNA链中,停止DNA复制,从而诱导凋亡。非复制性载体直接传递到肿瘤部位,使得非毒性治疗对胶质瘤治疗有价值。

一项随机的II期临床试验(NCT00870181)评估了使用Adv-TK结合GCV的病毒疗法在复发性III级和IV级恶性胶质瘤患者的安全性和有效性。该研究被认为是安全的,并显示了与标准治疗相比,使用Adv-TK治疗的患者6个月无进展生存期(PFS-6)、无进展生存期(PFS)和总生存期(OS)有所改善。

一项II期前瞻性临床试验(NCT00589875)评估了基因介导的细胞毒性免疫疗法(GMCI)在新诊断的恶性胶质瘤中的有效性和安全性。该方法使用了AdV-TK以及缬氨酸酯GCV(为提高GCV在大脑中的生物利用度而开发的GCV的缬氨酸酯),结合标准放疗和化疗。研究报告称,肿瘤切除更大的患者在联合疗法中的中位OS为25个月,而单独标准治疗(SOC)为16.9个月,3年生存率分别为32%和6%。另一方面,一项针对儿童脑肿瘤的I期临床试验(NCT00634231),结合了AdV-TK瘤内注射和GMCI以及标准治疗,显示出可接受的安全性结果,在8名患者中有3名患者生存超过24个月,2名患者在治疗后37.3和47.7个月没有肿瘤进展。几项已完成或正在进行的临床试验针对新诊断或复发性GBM使用了腺病毒HSV1-TK/缬氨酸酯(NCT03596086和NCT03603405),或HSV1-TK/缬氨酸酯与AdV-Flt3L(NCT01811992)结合,或与Nivolumab(NCT03576612)结合。然而,使用腺病毒疗法与其他疗法结合的前瞻性随机研究将是必要的,以评估这些方法的实际有效性并改善胶质瘤患者的临床结果。

此外,非复制性腺病毒载体基因治疗已被用作免疫增强疗法,以增强抗肿瘤免疫反应。一种新的方法使用Adv载体表达人类白细胞介素-12(IL-12)在RheoSwitch系统®(Ad-RTS-hiL-12)的控制下(Ad-RTS-hiL-12)结合激活剂veledimexin(VDX)被开发出来。一项多中心I期临床试验(NCT02026271)针对复发性高级别胶质瘤,表明可接受的耐受性和有希望的初步结果,显示增加的肿瘤浸润性淋巴细胞支持hIL-12在复发性胶质母细胞瘤中的免疫反应。然而,皮质类固醇对与VDX剂量相关的总生存期有负面影响,将这项试验扩展到I期子研究(NCT03679754),以评估hIL-12作为复发性或进展性GBM患者的单药治疗。

另一项I期剂量递增,多中心临床试验(NCT03636477)使用了Ad-RTS-hIL-12/VDX基因治疗与免疫检查点抑制剂药物(Nivolumab)结合治疗复发性胶质母细胞瘤。这种方法显示出联合免疫疗法的安全性结果,并似乎正朝着正在进行的II期临床试验Ad-RTS-hIL-12 + Veledimex与Cemiplimab-rwlc结合治疗复发性胶质母细胞瘤(NCT04006119)。一项I期临床试验(NCT03330197)已扩展到儿童脑肿瘤,以评估Ad-RTS-hIL-12/VDX疗法的效果,但由于进展缓慢,于2021年终止。

溶瘤腺病毒疗法是另一种正在研究用于治疗胶质母细胞瘤的方法。这种疗法基于对AdV的工程改造,使其在肿瘤细胞中有条件地复制并诱导细胞溶解,暴露癌细胞抗原,最终刺激免疫反应。

溶瘤腺病毒DNX-2401(Tasadenoturev)被创造出来,目标是针对视网膜母细胞瘤途径突变的肿瘤细胞。最近已完成或正在进行的几项临床试验使用了这种药物。使用DNX-2401的第一项临床研究是一项I期,剂量递增研究,具有生物学终点,针对复发性高级别胶质瘤患者(NCT00805376)。研究报告称,20%的患者存活超过3年,37名患者中有3名患者肿瘤减少超过95%,导致从治疗开始超过3年的PFS。因此,DNX-2401治疗可能由于溶瘤效应诱导了抗肿瘤反应,随后诱导了免疫介导的反应。结果支持了研究的安全性。

在Ib期研究中,IFN-γ表达的增加并没有改善患者生存(TARGET-I;NCT02197169)。同样,另一项I/II期临床试验使用DNX-2401,通过肿瘤内导管给药,已在荷兰进行(NCT01582516)。对研究患者的脑脊液(CSF)分析表明,DNX-2401治疗增加了一些细胞因子的水平,如肿瘤坏死因子α(TNF-α)、白细胞介素6(IL-6)和干扰素γ(IFN-γ)。用患者的CSF进行体外治疗增加了巨噬细胞中CD64(M1促炎极化)的水平。其他研究使用了DNX-2401与免疫疗法的结合。目前正在进行的II期临床试验(CAPTIVE,NCT02798406)正在检查Pembrolizumab(一种抗PD-1抗体)治疗与溶瘤DNX-2401治疗的结合效果。此外,一项I期试验结合溶瘤DNX-2401疗法和TMZ正在进行复发性胶质母细胞瘤的治疗(NCT01956734)。进一步,第一项I期试验正在测试第三代DNX-2440表达共刺激OX40L,用于复发性胶质母细胞瘤(NCT03714334)。对于儿童脑肿瘤(DIPG),一项评估DNX-2401治疗的I期临床试验目前正在进行(NCT03178032)。

我们的实验室在过去20年中一直专注于改善治疗性转基因进入大脑的传递。我们开发了第一代重组腺病毒载体,传递条件性细胞毒性酶HSV1-胸苷激酶(Ad.TK)和细胞因子Flt3L(Ad.Flt3L)用于脑癌治疗。这些载体在所有物种的胶质瘤细胞中表现出非常高的转导效率,从啮齿动物、狗到人类。Ad.TK转导的细胞能够磷酸化核苷类似物GCV。磷酸化的GCV被引入新生的DNA链中,但它阻止了延伸,导致复制细胞的凋亡,增加了肿瘤抗原和损伤相关分子模式(DAMPs)在肿瘤微环境中的可用性。另一方面,Ad.Flt3L转导的细胞释放Flt3L,这招募树突状细胞进入肿瘤。

我们实验室的广泛临床前研究已经证明,这种联合疗法能够触发抗肿瘤免疫反应,导致胶质瘤的根除和相关胶质瘤模型中的免疫记忆,即使与标准化疗联合使用也是如此。鉴于这些载体在神经病理学方面的卓越表现以及在实验性胶质瘤中的强效抗肿瘤效果,FDA批准了一项I期剂量递增试验,该试验在新诊断的、可切除的恶性胶质瘤患者中进行(NCT01811992)。在肿瘤切除手术期间,患者接受了两种载体在肿瘤腔中的递增剂量,随后是瓦拉西克洛韦(2)和TMZ与放疗的周期。治疗耐受性良好,未达到最大耐受剂量(MTD)。初步数据分析表明,这种治疗提供了临床上显著的生存期,并值得进一步临床评估这一策略。

尽管在实验性胶质瘤和GBM患者中使用这种第一代腺病毒平台获得了有希望的结果,但通过使用逃避免疫系统的新世代载体,这种策略可以进一步改进,因为第一代腺病毒载体仍然具有免疫原性。尽管在未系统性接触过病毒抗原的天真啮齿动物中颅内给予这些载体可以导致Ad编码转基因的稳定长期表达,但很大一部分人类患者由于之前的感染和疫苗接种而表现出预先存在的抗Ad免疫。我们已经证明,预先存在的抗Ad免疫导致大脑中Ad介导的转基因表达减少,持续时间不到2周。因此,我们开发了高容量腺病毒载体,它们没有所有Ad基因,使它们几乎对免疫系统不可见,并允许更大的有效载荷容量。我们使用这些载体在胶质瘤模型中传递TK和Flt3L,并发现即使在预先免疫抗腺病毒载体的动物中,它们也能导致强大的治疗效果。

这些载体更大的克隆能力允许在一个载体中包含两个治疗基因或添加调节序列,例如诱导型启动子。诱导型启动子允许通过添加/耗尽诱导剂来控制转基因表达,允许在出现不良反应时停止转基因表达。我们在高容量Ad中包含一个TetOn开关以控制Flt3L的表达,在体外和体内都显示出非常严格的基因表达控制。尽管高容量Ads尚未在人类患者的大脑中注射,但对它们的神经病理学和生物分布的临床前评估表明,这些载体可能是治疗性转基因表达在大脑中的有用工具,即使在预先存在的抗Ad免疫的情况下,也值得在临床试验中进一步评估。

3.HSV载体

单纯疱疹病毒1型(HSV-1)是人类感染病毒,属于疱疹病毒科。它们是第一个被设计用来治疗脑肿瘤的溶瘤病毒。HSV是一种双链DNA,包膜病毒,具有152 kb的病毒基因组。HSV病毒的基因组包含74个已知的ORF和两个独特的区域,称为长区域(UL),包含56个病毒基因,以及短区域(US),包含12个基因。溶瘤HSV显示出多种优势,使其成为基因治疗用途的有吸引力的选择。HSV具有高度传染性,能够在体外感染许多细胞类型;许多基因对体外生长非必需,并且可以被删除以插入外源性转基因。HSV-1可以生长到高滴度和纯度,并且对复制和包装的要求最小。HSV-1是神经营养性的,有助于选择性靶向神经病理学。此外,删除γ34.5基因最小化了非肿瘤性脑细胞的损伤。此外,HSV-1诱导细胞死亡,并启动和改善抗肿瘤免疫反应。由于所有这些优势,目前有多个正在进行的临床试验使用溶瘤HSV-1治疗脑肿瘤。

大多数基于HSV-1的临床试验使用了HSV-G207,这是一个载体,包括删除两个γ34.5副本,并在UL39基因中插入大肠杆菌β-半乳糖苷酶基因(LacZ),该基因抑制DNA合成和HSV-1在正常细胞中的复制。此外,这个载体包含胸苷激酶(TK)基因。这种疗法的作用机制基于通过溶瘤作用诱导胶质瘤细胞死亡,并增强肿瘤浸润的细胞毒性免疫效应物。两项I期和II期临床试验已经完成(NCT00157703和NCT00028158)。放射影像结果显示单剂量HSV治疗的安全性和潜在治疗反应,并随着放射治疗而增加。

使用溶瘤HSV-G207治疗进展性幕上儿童脑肿瘤的研究正在进行中。一项I期临床试验(NCT02457845)使用G207与放射治疗联合的肿瘤内接种,显示没有剂量限制性毒性效应,在12名患者中的11名患者中显示出临床、放射影像和病理反应,并显著增加了淋巴细胞肿瘤浸润。目前,另一项II期临床试验将评估HSV-G207和单剂量放射治疗在儿童复发性高级别胶质瘤中的效果(NCT04482933),以及在复发性小脑脑肿瘤中的I期临床试验(NCT03911388)。

HSV-G207的改良版,G47Δ,是一个第三代溶瘤疱疹,通过从亲本G207中删除α47基因和重叠的US11启动子构建而成,亲本G207是一个第二代溶瘤HSV-1,具有在两个γ34.5基因副本中的删除和ICP6基因的失活。这种溶瘤病毒已在日本的2期试验中进行了测试(UMIN000015995)。最近的报告表明,使用HSV G47Δ在残留或复发GBM患者中产生了生存益处和良好的安全概况。给药包括在MRI引导的立体定向手术中进行肿瘤内注射,第一和第二剂量间隔5-14天,第三和后续剂量最多六次,间隔4±2周。总体中位生存期为G47Δ开始后20.2(16.8-23.6)个月,从初始手术起28.8(20.1-37.5)个月(Todo等人,2022年)。由于复发GBM在标准治疗后的中位生存期约为6.0个月,这些结果显示出显著的改善。

HSV-207的进一步发展包括通过插入促炎细胞因子IL-12来增强适应性免疫反应的激活的改良(M032-HSV-1)。目前正在进行一项I期临床试验(NCT02062827),使用这种方法治疗复发性高级别胶质瘤。

此外,目前还有一项I期临床试验(NCT03152318)正在积极使用rQNestin γ34.5v2治疗复发性高级别胶质瘤。这种疗法是以前方法的变体,因为溶瘤HSV载体包括一个γ34.5基因的删除,第二个副本的这个基因被放置在nestin启动子的控制下,从而使得病毒感染的胶质瘤肿瘤细胞表达高水平的nestin时能够进行病毒复制,而不允许在正常细胞中复制。患者在手术期间接受肿瘤内注射,有或没有术前给予环磷酰胺。初步结果显示,在治疗下的患者血清中检测到CCL2和IL-10的产生。进一步的结果将通知溶瘤rQNestin γ34.5v2的安全性和有效性以及环磷酰胺对先天免疫反应的影响。

3.1.逆转录病毒载体

逆转录病毒是含有单链正义RNA的病毒。逆转录病毒基因组由两个副本的单链高度浓缩的RNA分子组成,长度为7-12 kb(Goff,1992年)。RNA基因组被包裹在二十面体蛋白壳和脂蛋白包膜中。小鼠白血病病毒衍生的复制能力伽马逆转录病毒可以整合高达8 kb的外源DNA,并且只能转染增殖的有丝分裂肿瘤细胞。编码单纯疱疹病毒胸苷激酶(HSV-TK)的逆转录病毒载体是第一个在临床试验中测试用于治疗脑癌的递送系统(NCT00001328)。表达HSV-TK的胶质瘤细胞在接触前药GCV(Cytovene)后死亡。试验的初步发现揭示了对小肿瘤和复发性胶质瘤患者的抗胶质瘤活性。从长远来看,该系统的效率低于预期,OS不支持这种方法的进一步发展。

Vocimagene amiretrorepvec(Toca 511)是一种针对肿瘤的、非溶瘤复制能力伽马逆转录病毒载体,表达胞嘧啶脱氨酶(CD)。前药5-氟胞嘧啶(5-FC)可以被CD激活,产生5-氟尿嘧啶(5-FU)。这种分子抑制胸苷酸合成酶,并将这种代谢物并入RNA和DNA,导致细胞死亡。Toca 511和5-FC的缓释制剂与TMZ联合使用提高了对TMZ敏感胶质瘤的治疗效果。联合治疗(Toca 511 + 5-FC)被发现可以使胶质瘤对放射疗法敏感。多项临床试验使用这种组合治疗复发性高级别胶质瘤患者(NCT01156584;NCT01156584;NCT01985256)。在I期试验中,接受Toca 511加Toca FC治疗的rHGG患者显示出有希望的治疗反应,并将在未来的随机III期临床试验中进一步评估联合治疗。治疗未能达到预期。Toca 511加FC组与活性对照组之间没有显著差异(mOS:11.10 vs. 12.22个月)。

3.2.慢病毒载体

慢病毒是正链、单链RNA病毒,已被广泛研究,用于对抗GBM的潜在应用。与逆转录病毒不同,慢病毒载体(LV)整合到宿主基因组中,但不太可能发生插入性突变。由于LV可以在非分裂细胞中复制,它们为在中枢神经系统终末分化细胞中延长转基因表达提供了一个吸引人的选择。最著名的慢病毒是HIV-1衍生的,最初观察到它转导淋巴细胞和非分裂细胞。此外,牛免疫缺陷病毒(BIV),猴和猫(FIV)免疫缺陷病毒,马传染性贫血病毒(Poeschla,2003年),绵羊肺病病毒(MVV)和山羊关节炎脑炎病毒也被用作基因治疗载体的来源。与伽马逆转录病毒相比,LV具有更大的转基因容量(高达18 kb),并且已经创建了具有增加转导效率和安全性的第三代基于HIV的载体。这些载体可以通过伪型化实现组织嗜性,并且由于缺乏病毒蛋白合成表达,表现出低免疫原性。

包括胶质瘤干细胞在内的GBM细胞在被假型化的淋巴细胞性脉络丛炎病毒糖蛋白的LV感染时,比正常脑细胞具有更高的转导效率。LV是用于沉默RNA或创建表达针对GBM抗原的嵌合抗原受体的T细胞的首选载体。带有p2A肽的双重表达系统的LV允许在CMV启动子的控制下表达肿瘤抑制蛋白,生长停滞特异性(GAS)-1和磷酸酶和张力蛋白同源物(PTEN),这种载体在体外抑制了人类GBM细胞的生长,并减缓了人类GBM异种移植模型中胶质瘤的进展。通过编码特定于孤儿核受体TLX(NR2E1)的shRNA的LV,抑制了小鼠中人类胶质瘤干细胞的肿瘤形成能力。这种受体在早期胚胎发育过程中的神经发生中发挥着重要作用,并在维持干细胞特性和控制成人神经干细胞在中枢神经系统中的分化中发挥着关键功能。它对神经干细胞的更新是必需的,并诱导DNA羟化酶ten-eleven易位3(TET3)的表达,这是TLX下游的一个强大的肿瘤抑制因子。使用LV编码的簇状规则间隔短回文重复(CRISPR)和CRISPR相关(Cas)9系统。通过这种方法,敲除转录增强因子1(TEAD1)减少了人类GBM细胞的运动,并改变了迁移和上皮-间充质转化(EMT)转录组签名。

在临床前基因治疗模型中,慢病毒(LV)已被用于表达多种RNA分子,包括miRNAs、AntagomiRs、siRNAs和shRNAs,对于人类应用的成果令人鼓舞。在原位胶质瘤异种移植模型中,慢病毒介导的血管内皮生长因子(VEGF)/VEGF受体(VEGFR)信号通路的沉默与肿瘤体积减小、基质金属蛋白酶9(MMP9)免疫反应性丧失和肿瘤坏死增加相关。一项I期临床试验使用慢病毒载体编码嵌合抗原受体(CAR),识别肿瘤抗原表皮生长因子受体变体III(EGFRVIII)、白介素-13受体α2(IL13Rα2)、人表皮生长因子受体2(Her-2)、EphA2型受体(EphA2)、prominin-1(CD133)、神经节苷脂g2(GD2),单独或联合抗PDL1抗体,目前正在评估针对复发性恶性胶质瘤患者的个性化CAR-T细胞免疫疗法的安全性和有效性(NCT03423992)。自体T细胞通过慢病毒转导重定向至EGFRVIII的CAR在EGFRVIII+胶质母细胞瘤患者中也处于I期临床试验(NCT02209376),结果显示EGFRvIII导向策略的治疗效力得到改善。

3.3.腺相关病毒载体

腺相关病毒(AAV)是一种小的单链DNA非包膜病毒,具有复制缺陷,属于非致病性细小病毒科。AAV是非自主性的,需要辅助病毒,如腺病毒或HSV,才能在宿主细胞内复制。AAV有几个优点,即它能以高效率感染多种分裂和非分裂细胞,此外其较小的体积使其能更好地渗透实体瘤如胶质瘤。在人类和小鼠GBM模型中,单次脑内注射编码人IFN-β的AAV显示增强的胶质瘤细胞死亡和提高长期存活。在侵袭性胶质瘤的原位异种移植小鼠模型中,颅内AAV设计分泌可溶性肿瘤坏死因子相关凋亡诱导配体(sTRAIL),联合兰托昔康延长中位生存期。在体外人类胶质母细胞瘤细胞系中,重组腺相关病毒(rAAV)编码组织因子途径抑制物2(TFPI-2)抑制侵袭、血管生成和肿瘤形成。在没有辅助病毒的情况下,AAV基因组建立潜伏状态,大部分作为游离基因存在。只有一小部分AAV载体基因组整合到宿主细胞的基因组中,因此核拷贝数随着每次细胞分裂而减少,AAV载体更受青睐于短期转基因表达。在GBM的临床前模型中,AAV介导的脑肿瘤细胞基因改变,表达抗肿瘤蛋白的基因,尽管这些肿瘤的转导效率较低,但已显示出令人鼓舞的结果。通过DNA重组选择由不同cap基因重组产生的嵌合AAV衣壳库,开发了一种快速工程化AAV载体的方法,提高了转导效率,从而增强了治疗效果。与腺病毒载体相比免疫原性降低,高滴度生产和伪型化选项都是基于AAV的载体的优势。预计不久的将来,这些载体将因使用AAV的临床前基因治疗研究的鼓舞人心的结果而促进对胶质母细胞瘤治疗的临床评估。

3.4.新城疫病毒、麻疹病毒和杆状病毒载体

新城疫病毒(NDV)是一种高致病性禽类单链RNA病毒,基因组为16 kb,但通常只引起人类的轻微喉炎和结膜炎。NDV在鸟类中可分为弱毒(lentogenic)、中等毒力(mesogenic)或强毒(velogenic),根据其致病性。基于NDV的载体对肿瘤细胞具有天然亲和力,以及溶瘤和免疫刺激能力。与单独使用TMZ相比,辅以自然溶瘤NDV的LaSota株促进了胶质瘤细胞的增强凋亡。使用反向遗传学开发了重组NDV载体,作为潜在有效的癌症治疗剂。NDV已被证明能诱导肿瘤特异性溶瘤,但这一机制尚不明确。溶瘤病毒优先以免疫原性方式靶向和消除癌细胞,从而促进治疗相关肿瘤特异性免疫反应的发展。在复发性GBM、肉瘤和神经母细胞瘤患者中评估静脉注射NDV-HUJ溶瘤病毒的I/II期试验(NCT01174537),尽管这项试验最终被撤回。麻疹病毒(MV)是一种包膜单链RNA病毒,引起麻疹,极少数情况下引起脑炎。MV的两个主要蛋白支持MV的溶瘤活性,显示出在胶质瘤治疗中的前景。MV血凝素糖蛋白对宿主细胞上的受体如nectin-4和CD46具有高亲和力。CD46受体在肿瘤细胞中高度过表达,包括胶质瘤。MV的融合蛋白介导细胞融合,诱导这些细胞的凋亡。高度减毒的Edmonston株(MV-Edm)表达癌胚抗原(CEA)具有高度致病性,对胶质瘤具有潜在的治疗效力。在复发性GBM患者中进行的MV-CEA剂量递增I期临床试验(NCT00390299)中未见剂量限制性毒性。最初,通过遗传工程的溶瘤麻疹病毒株对胶质瘤的抗癌活性由Phuong等人在体内外证明。最近,改良的MV-NIS在I期临床试验中进行评估(NCT02962167),用于治疗儿童和青少年复发性髓母细胞瘤或复发性非典型畸胎样/横纹肌样瘤(ATRT)。杆状病毒(BV)载体是另一种可能用于基因治疗的病毒。BV是包膜双链DNA病毒,通常感染昆虫,不在人类细胞中复制,这使它们非常安全。人类对BV没有预先存在的免疫力,使它们可能对人类疗法有效。BV有一个约134 kb的DNA基因组,相对容易工程化,可以携带大型转基因,但尚未在临床试验中评估。BV避免了哺乳动物病毒载体的一些缺点,同时也为癌症基因治疗提供了另一种选择,编码白喉毒素A基因的BV显示出对恶性胶质瘤的增强效力。所有关键病毒载体临床试验总结在表1中。

4.非病毒载体

4.1.纳米颗粒和脂质体

由于非病毒载体如脂质体、纳米颗粒(NP)和聚合物载体相较于病毒载体具有更低的免疫原性和细胞毒性风险,它们在胶质母细胞瘤(GBM)治疗中的研究日益增多。脂质体是直径在400纳米至2.5微米之间的球形囊泡,能够包裹液态药物,通常包含化疗药物。它们无毒、生物相容且可生物降解。纳米颗粒直径在1至1000纳米之间,可以通过纳米沉淀、双重乳液溶剂蒸发或光刻技术制造。它们通常由生物相容性聚合物制成,这些聚合物被设计用来包含药理化合物,并且可以被功能化以选择性地结合不同的靶标位点,最终在几天或几周内降解。纳米颗粒还能独特地靶向多种配体,如抗体、肽、小分子和细胞表面蛋白。这些载体因其能够穿越血脑屏障(BBB)并在GBM肿瘤中特异性释放杀瘤药物而具有前景。尽管目前尚无非病毒载体获得FDA批准用于GBM治疗,但已有几种进入了临床试验,如下所述。

最有前景的脂质体基因疗法之一是SGT-53,这是一种靶向肿瘤的免疫脂质体复合物(SGT),包裹野生型p53质粒DNA。SGT-53能够穿越BBB,有效地将p53 cDNA传递给GBM细胞,从而恢复wtp53。2013年的初步1期临床试验(NCT00470613)显示,SGT-53治疗对患有不同类型晚期实体瘤的患者副作用最小。值得注意的是,在11名患者中有7名显示出强烈的抗癌活性,并且在靶向转移性肿瘤中积累了p53转基因,而不是正常皮肤组织。最近对SGT-53的研究集中在与标准治疗(SOC)GBM治疗的联合治疗上。SGT-53和替莫唑胺(TMZ)联合疗法提高了化疗敏感性,使肿瘤细胞对TMZ敏感,并在GBM小鼠模型中诱导凋亡。它还被证明可以减少,甚至逆转体外和体内对TMZ的耐药性发展。然而,2015年开始的TMZ和SGT-53联合治疗2期临床试验因报名人数不足于2021年终止。SGT-53与多西他赛联合的1b期研究(治疗多种癌症,包括胶质母细胞瘤)显示,在12名患者中毒性低且临床活性高,其中3名患者实现了RECIST验证的部分肿瘤反应,2名患者达到稳定疾病状态。此外,抗PD1抗体和SGT-53在GL261胶质母细胞瘤小鼠肿瘤模型中的联合疗法通过使原本对PD1抗体耐药的肿瘤对PD1抗体敏感,显示出增加的抗肿瘤效果。需要更多的临床工作将这些疗法带入2期和3期临床试验,并可能获得FDA批准。

另一种基于脂质体的纳米治疗正在由荷兰的Tellingen等人、2-BBB Medicines以及马萨诸塞州剑桥的2X Oncology, Inc.开发。谷胱甘肽聚乙二醇化脂质体阿霉素(2B3-101)是一种现有的脂质体,通过额外的谷胱甘肽涂层功能化以增强穿越BBB的传递。2B3-101已被证明在异种移植模型中显著抑制GBM生长,并正在进行两个针对转移性乳腺癌和GBM的2期临床试验(NCT01386580)。

纳米颗粒也被探索用于GBM治疗。尽管目前尚无FDA批准用于治疗胶质瘤的纳米颗粒,但2018年FDA批准了一种含有siRNAs的脂质纳米颗粒Patisiran,用于治疗一种神经退行性疾病,转甲状腺素介导的淀粉样变性。纳米颗粒由金属或碳骨架组成,包含或涂有抗GBM成分,如化疗药物或免疫细胞。它们也被制造成能够轻松通过BBB并靶向GBM细胞受体或血管生成血管。NU-0129是一种功能化siRNAs的球形金纳米颗粒,靶向肿瘤蛋白BCL-2类蛋白12(Bcl2L12)。2019年对8名GBM患者进行的0期临床试验发现NU-0129穿越了BBB,在肿瘤中积累,并减少了Bcl2L12蛋白的丰度,且未引起短期或长期毒性(NCT03020017)。2020年,Gregory等人开发了一种由聚合人血清白蛋白(HSA)和聚乙二醇(OEG)组成的合成蛋白纳米颗粒(SPNP)。SPNPs包含针对信号转导和转录激活因子3(STAT3i)的siRNA,并配备了细胞穿透肽iRGD。SPNPs穿透了BBB,在肿瘤中分布并传递针对STAT3的siRNA。在GBM小鼠模型中,SPNP与电离辐射联合使用,发现在87.5%的小鼠中导致肿瘤退缩和长期存活。

RNA纳米颗粒也被用来向肿瘤细胞传递核酸序列;针对致癌性miRNA-21的靶向抑制由基于三岔结构(3WJ)的RNA纳米颗粒(RNP)在2017年由Croce等人展示。继续这项工作,Lee等人创建了一种新的RNP,称为FA-3WJ-LNA-miR21,当针对胶质瘤细胞时,降低了它们的miR-21表达,总体上导致胶质瘤细胞死亡增加。这些研究表明,针对致癌性miRNAs的FA-3WJ RNP基础基因疗法具有临床效益,但尚未进入临床试验。

4.2.干细胞

干细胞是未分化的多能祖细胞,具有自我更新、迁移和分化的能力。干细胞主要可以分为两组:胚胎干细胞(ESC)和成人干细胞(ASC)。

ESC是多能细胞,意味着它们可以变成除胎盘中的细胞外的任何细胞类型。这一特性使它们成为一个强大的工具,但获取它们的唯一方式是从胚胎的内团细胞中分离出来。它们的起源引发了伦理考量,也正是因为这些担忧,治疗用途受到了限制。为了避免这个问题,2006年开发了一种协议,通过添加定义的因子(也称为山中因子)从体细胞建立多能干细胞,这些诱导多能干细胞(iPSC)是非胚胎细胞重新编程成为类似ESC的细胞,共享ESC的多能性,能够生成外胚层、中胚层和内胚层,并具有无限的复制能力。

ASC是存在于所有分化组织中的未分化前体细胞,并且可以重新填充它们。这组细胞包括造血干细胞(HSC)、间充质干细胞(MSC)和神经干细胞(NSC)。HSC可以从外周血、脐带血或骨髓中获得,是最容易获得的成人干细胞。它们可以产生髓系和淋巴系谱系。MSC是一种基质细胞,可以从许多不同的组织中分离出来,包括脐带、子宫内膜息肉、月经血、骨髓、脂肪组织和子宫内膜。它们可以产生成骨细胞、软骨细胞、单核细胞和脂肪细胞。唯一的内源性脑干细胞是NSC。这种细胞群主要可以在前脑的室管膜下区(SVZ)和海马体中找到。它们的多能性使它们能够产生神经元、星形胶质细胞和少突胶质细胞。

干细胞的功能涉及局部组织中的细胞修复,但它们也显示出靶向和迁移到肿瘤组织的能力,包括穿越血脑屏障(BBB),使它们成为基因传递的有用载体。植入或注射携带遗传修饰以产生抗肿瘤反应的祖细胞具有优势,因为这些细胞可以归巢到肿瘤细胞。干细胞治疗涉及外源性或动员内源性干细胞的给药。MSC和NSC都显示出对恶性胶质瘤的趋向性。

胶质瘤细胞外基质(ECM)以及分泌因子,指导多种细胞类型的细胞迁移。肿瘤表现出与慢性损伤相似的特点,如缺氧和炎症。在脑肿瘤中,微胶质细胞和星形胶质细胞产生血管生成和促炎因子。它们产生的趋化因子,以及肿瘤细胞和浸润性肿瘤细胞产生的VEGF、HIF1α、CCL-25、IL-6、CXCL16和CXCL12,吸引干细胞。使用小鼠模型的研究表明,MSC和NSC都迁移到脑肿瘤。NCS表达CCR2,这诱导迁移到单核细胞趋化蛋白-1(MCP-1/CCL2),在脑肿瘤病变中高度表达。NSC缺乏主要组织相容性复合体II型(MHC II),允许这些细胞的植入,能够在移植后逃避宿主的免疫反应。尽管有几种趋化因子介导干细胞对脑肿瘤的趋向性,但仍有许多需要学习的地方,涉及的分子机制也很多。然而,干细胞的迁移潜力强烈支持它们的治疗用途,特别是可能靶向远离主要肿瘤质量的肿瘤细胞。

干细胞基础治疗诱导细胞毒性最探索的途径之一是使用肿瘤坏死因子相关凋亡诱导配体(TRAIL)与肿瘤细胞表达的死亡受体(DR)的相互作用,当配体结合时激活caspase介导的凋亡。这一点得到了GBM表现出TRAIL介导的凋亡的支持。在胶质瘤异种移植模型中,由NSCs部署的可溶性TRAIL(sTRAIL)显示出改善生存和显著减少肿瘤负担。尽管TRAIL已在动物模型中进行了研究,但尚未进入人类试验。

另一种使用干细胞的方法是酶促前药激活。NSC可以用来传递在肿瘤微环境中激活前药的酶。NSC可以被修改以表达HSV1-TK,然后可以在给药后催化GCV的转化。同样,5-FC前药可以被胞嘧啶脱氨酶激活,产生细胞毒性5-FU。上述在腺病毒部分和逆转录病毒部分分别描述了HSV1-TK加GCV和CD加5-FC的两种前药激活机制。另一种利用酶促前药激活的修改是在干细胞中诱导表达兔子羧酸酯酶,可以将伊立替康转化为有毒的拓扑异构酶-1抑制剂SN-38。

利用干细胞的不同方法,从它们的趋向性中获益是传递溶瘤病毒。在胶质瘤的小鼠异种移植模型中,转染有复制能力溶瘤腺病毒(CRAd)的人类MSC表现出迁移到大脑的能力,当在远离肿瘤部位注射时,并向胶质瘤细胞传递CRAd。这种基于干细胞的治疗方法可以改善胶质瘤的溶瘤病毒疗法。感染有复制能力病毒的干细胞是将病毒传递到肿瘤的创新方式,以产生病毒感染,随后导致肿瘤细胞死亡。

目前FDA批准的唯一干细胞程序是HSC给药,用于治疗多发性骨髓瘤、白血病和血液疾病。第一个使用干细胞进行神经肿瘤学研究的人类研究由Portnow等人进行。这项研究涉及15名复发性GBM患者,他们接受了一次剂量的颅内注射,基因修饰的NSC,表达CD,加上前药5-FC,作为单剂量(NCT01172964)。它显示了总体生存没有差异。尽管如此,这项研究确立了NSC的安全性,以及干细胞局部产生化疗药物,即5-FU的有效性。脑解剖证明NSCs不是肿瘤性的,也证明它们迁移到远处的肿瘤部位。这是NSCs靶向脑肿瘤和局部产生化疗药物的能力的概念验证。后续研究显示了NSC-CD加5-FC的剂量递增,多次治疗轮次,与5-FC和叶酸(亚叶酸)联合使用(NCT02015819),旨在确定用于2期的剂量。

正在临床试验中探索的另一种酶前药系统是使用修饰后的NSC(神经干细胞)表达羧酸酯酶加上前药伊立替康。一个目前活跃但尚未开始招募的1期临床试验,针对复发性高级别胶质瘤,将在第1天和第15天进行两次表达羧酸酯酶的异体NSC给药(NCT02192359)。还有新的临床试验旨在研究基于干细胞的疗法以改善病毒传递。在这方面,针对新诊断的恶性胶质瘤的1期临床试验(NCT03072134)采用了表达CRad-S-pk7的NSC,这是一种溶瘤腺病毒。NSC-CRad-S-pk7在切除术后被植入颅内。这项试验能够证明治疗的安全性,并正在进入2/3期临床试验(Fares等人,2021年)。即将开始招募的1期临床试验(NCT05139056)将使用NSC-CRad-S-pk7治疗复发性高级别胶质瘤,通过颅内给药每周一次,持续10分钟,最多4剂。另一种与干细胞结合使用的病毒疗法是1期临床试验(NCT03896568),使用骨髓来源的MSC,装载溶瘤腺病毒DNX-2401,在复发性GBM、胶质肉瘤或野生型IDH-1间变性星形细胞瘤患者中。截至目前尚未报告结果。在1至21岁的患者中,目前正在招募的临床1/2期试验,使用AloCELYVIR治疗弥漫性内生脑桥胶质瘤(DIPG),AloCELYVIR是骨髓来源的异体MSC感染的溶瘤腺病毒ICOVIR-5(NCT04758533)。患者将每周接受AloCELYVIR输注8周。结果即将公布。所有关键的非病毒载体临床试验总结在表2中。

5.结论

尽管弗里德曼在1972年提出了人类疾病基因治疗的概念(弗里德曼和罗布林,1972年),并且目前有大量的临床前数据支持,但神经学和神经肿瘤疾病的治疗仍在进入临床领域。第一个被政府机构批准的基因治疗产品是Gendicine,一种重组人类p53腺病毒。它在2003年被中国食品药品监督管理局(CFDA)批准,用于治疗头颈癌。在西方国家,第一个基因治疗在2012年到来,当时欧洲委员会批准了Glybera,这是一种AAV1病毒载体,传递完整的人类脂蛋白脂酶(LPL)基因副本,以逆转脂蛋白脂酶缺乏症(LPLD)。美国在2015年批准了第一个基因治疗。FDA批准的第一个溶瘤病毒疗法是Talimogene laherparepvec,这是一种首创的、基因修饰的、基于1型单纯疱疹病毒的溶瘤免疫疗法,用于局部治疗初次手术后复发的黑色素瘤患者的不可切除的皮肤、皮下和淋巴结病变。2017年,FDA批准了第一个嵌合抗原受体(CAR)T细胞免疫疗法。Tisagenlecleucel,基因修饰的自体T细胞表达嵌合抗原受体,靶向B细胞(CD19),被批准用于治疗急性淋巴细胞性白血病的儿童和年轻成人。此外,到2017年底,FDA批准了第一个针对特定基因突变引起的疾病的目标基因治疗。由视网膜色素上皮特异性65(RPE65)的两份副本突变引起的遗传性视网膜疾病(IRD),目前通过AAV2的次视网膜注射传递这种酶的功能副本进行治疗。这是美国批准的第一个AAV疗法。2019年,FDA批准了第一个用于治疗两岁以下儿童的脊髓性肌萎缩症(SMA)的基因治疗,使用AAV9介导的基因传递完整的SMN1。每年,FDA都在纳入更多的细胞和基因治疗,并且还在重新利用已批准的治疗方法。基因治疗是一个有前景和多功能的工具,在神经肿瘤学中,因为它可以在初次肿瘤切除时局部给药,最小化系统毒性的风险。高级别胶质瘤高度异质性和侵袭性。基因组编辑旨在克服治疗抗性和减少复发。病毒治疗提供了能够到达不能切除的侵袭性细胞的治疗方法。多年来,采用各种基因组编辑策略的不同载体已被证明是安全的(图1)。基于干细胞的疗法目前作为一种安全有效的方式实现基因传递而出现。它在临床上作为激活酶前药系统和使用溶瘤病毒的新机制而出现(图1)。基于干细胞的疗法可以通过提供额外的肿瘤趋向性进一步改善基因治疗。临床前数据甚至支持使用联合纳米颗粒和干细胞作为载体。最后总结,我们相信,单独和联合使用基因治疗、纳米颗粒和干细胞,为实现胶质母细胞瘤和其他脑肿瘤的成功治疗提供了最大的希望。

图1. 使用基因治疗载体和干细胞治疗胶质瘤的临床方法。病毒载体是基因治疗中最常用的工具。病毒载体包括源自腺病毒(AdV)、疱疹病毒(HSV)、逆转录病毒、新城疫病毒(NDV)和麻疹病毒(MV)的载体。非病毒载体包括纳米颗粒、脂质体和干细胞。在胶质瘤治疗中使用的干细胞是神经干细胞(NSC)或间充质干细胞(MSC)。基因治疗中最常用的治疗技术之一是自杀疗法。这涉及到酶加前药的系统:(1)表达单纯疱疹病毒胸苷激酶(HSV-TK),加上更昔洛韦(GCV)治疗,(2)表达胞嘧啶脱氨酶(CD),加上5-氟胞嘧啶(5-FC),(3)表达兔羧酸酯酶,加上伊立替康。自杀疗法已经用病毒和非病毒载体进行了探索。其他使用的治疗效果基因包括免疫调节剂如Flt3L和IL-12;肿瘤抑制靶点,如野生型p53,或在CAR-T细胞中表达的嵌合抗原受体,包括EGFRvIII、CD1322、Her-2。还有溶瘤病毒疗法,使用的溶瘤病毒(AdV、HSV-1、NM和NDV)能够识别、感染并裂解不同的细胞。此外,MSC和NSC也被用来传递溶瘤病毒。

放射疗法基因疗法细胞疗法免疫疗法临床研究

2024-02-07

·药时代

前言多形性胶质母细胞瘤(GBM)是成人最常见的原发性中枢神经系统(CNS)恶性肿瘤。目前所有的标准护理治疗对其均效果不佳,预后差,5年总生存率仅为6.8%。GBM的治疗标准包括最大限度安全的肿瘤切除,然后是放疗(RT)和替莫唑胺(TMZ)联合化疗。与单纯放疗相比,联合治疗的中位总生存期(OS)分别为14.6个月和12.1个月。2015年,FDA批准了一种新的电物理治疗模式,即GBM患者的肿瘤治疗场(TTFields)。III期(NCT00916409)临床试验证明,TTFields治疗的中位无进展生存期(PFS)提高到6.7个月,而替莫唑胺组为4.0个月。中位OS也显著改善,分别为20.9个月和16.0个月(p<0.001)。然而,几乎所有GBM都会复发。可用的治疗方案包括二线手术、放疗、烷化剂化疗和贝伐单抗治疗。不幸的是,从第一次进展或复发开始,中位OS的范围仅为6到9个月。因此,迫切需要新的治疗策略来治疗复发性GBM。免疫疗法是一种利用患者自身免疫系统对抗肿瘤的新型疗法,它彻底改变了多种癌症的治疗方式,虽然到目前为止,免疫疗法在GBM的治疗还未取得突破,但值得注意的是,先前接受放疗和化疗治疗的复发性GBM通常具有更高的突变负荷,并且预期比未经治疗的GBM患者具有更高的免疫原性,这增强了人们对免疫治疗的信心和乐观态度。对其生物学、免疫微环境的进一步理解以及新的治疗组合方法的出现,可能会改变目前免疫疗法在GBM的困境。中枢神经系统的免疫特权长期以来,中枢神经系统一直被认为是一个免疫特权系统:由于血脑屏障(BBB)阻挡了病原体,CNS比任何其他器官接触病原体的机会要少得多。从在进化上,由于不需要经常发动免疫攻击,而且对脑细胞自动免疫的后果,抑制中枢神经系统的免疫可能是有利的。直到2015年,人们普遍认为中枢神经系统缺乏功能性淋巴管。由于这些是免疫反应的重要组成部分,因此很难理解抗原呈递是如何发生的。另外,BBB本身也被认为是有效免疫反应的限制因素,因为它的紧密连接在物理上阻止了免疫参与者(如淋巴细胞或抗体)的进入。中枢神经系统和其他器官之间的一个关键区别在于大脑中几乎没有用于抗原呈递的树突状细胞。在中枢神经系统中,小胶质细胞被认为是主要的抗原呈递群体,它主要为抗炎表型,使T细胞倾向于免疫抑制Th2表型。然而,现在已经有许多确切的证据表明,主动免疫监测确实发生在中枢神经系统中,并且针对感染产生有效的免疫反应。此外,多发性硬化症等自身免疫性疾病也表明,免疫原性抗原可以在中枢神经系统中被处理并触发强大的免疫反应。2015年,沿硬脑膜静脉窦通向颈深淋巴结的淋巴通路的发现极大地改变了我们对大脑免疫环境的概念。今天,虽然中枢神经系统被认为是一个免疫学上与众不同的部分,但人们相信它的免疫微环境为针对脑肿瘤的免疫治疗提供了合适的条件。GBM的免疫逃避机制GBM是最致命的脑癌,生长迅速,复发频繁,这一事实可归因于多个因素,包括高增殖率、高组织侵袭能力、抗治疗的癌症干细胞以及药物难以进入中枢神经系统。除此之外,免疫逃避在GBM预后不良中也起着关键作用。许多免疫逃避机制参与其中,包括通过完整的血脑屏障阻止免疫细胞进入,肿瘤微环境的免疫抑制,或通过劫持关键免疫途径和参与者,如免疫检查点受体表达、调节性T细胞、肿瘤相关巨噬细胞的调节。GBM具有对免疫攻击很高的内在抗性机制以及出色的适应能力,一项关于GBM中PD-1阻断的研究显示,只有少数患者出现初始反应,并且所有患者都复发。复发肿瘤活检的病理学表现为免疫抑制分子的新表达和新抗原表达的丢失。首先,GBM从其在中枢神经系统中的位置获得免疫抑制特性。其次,GBM受益于肿瘤组织的复杂异质性。此外,GBM还受益于有利的微环境,甚至进一步使其具有免疫抑制作用。一项研究表明,针对中枢神经系统抗原的CD8+T细胞在进入中枢神经系统后被迅速清除,证明了中枢神经系统微环境的耐受作用。在炎症环境中,干扰素诱导的趋化因子激活内皮细胞并允许外周免疫细胞穿过BBB。GBM则通过上调基质中的化学吸引蛋白并从外周招募MDSC和TAM等抑制性单核细胞来逃避免疫作用。最后,GBM免疫治疗的一个障碍是医源性免疫抑制。在GBM中,放射治疗与替莫唑胺联合化疗是标准治疗方法。一项研究表明,这种治疗导致3/4的患者的CD4+T细胞计数下降到300细胞/mm3以下。此外,替莫唑胺在PD-1阻断的临床前试验中阻止了记忆T细胞的诱导产生。肿瘤疫苗治疗与用于预防传染病的预防性疫苗一样,抗癌疫苗由添加了佐剂的肿瘤抗原组成,以期触发和增强免疫反应。在GBM中考虑了三种主要方法:(1)肽/DNA疫苗;(2)DC疫苗;(3)mRNA疫苗。最早也是评估最多的疫苗方法之一涉及EGFR的选择性剪接变体III(vIII),它是由外显子2到7的选择性剪接产生的肿瘤特异性抗原。EGFRvIII在25–30%的GBM肿瘤中表达。Rindopepimut(CDX-110)是研究最广泛的EGFRvIII肽疫苗。它使用免疫调节蛋白KLH作为佐剂,其在2015年2月被FDA认定为GBM的“突破性疗法”,II期数据显示,与对照相比,PFS和OS有均所改善。为了提高对GBM产生有效免疫反应的几率,人们将多种肿瘤特异性抗原结合到一种疫苗中。IMA950是一种肽疫苗,它结合了11种GBM衍生抗原,该疫苗已被证明能诱导T细胞对单个和多个抗原的反应。然而,目前还没有进行随机临床试验,因此这种免疫反应是否确实导致临床结果的改善还有待证明。树突状细胞是一种强大的抗原呈递细胞,能够诱导抗原特异性T细胞应答。迄今为止,已有两项随机试验评估了DC疫苗的疗效。ICT-107是一种针对肿瘤和癌症干细胞六种抗原的自体DC免疫疗法,包含MAGE-1、AIM-2、HER2/neu、TRP-2、gp-100和ILRa2。在一项涉及124名患者的双盲、安慰剂对照试验中,75名患者在RT和伴随TMZ后接受ICT-107治疗。结果显示,治疗组的PFS中位数略高于对照组(11.2个月vs 9个月;HR:57,p=0.011),但OS无差异(17.0个月vs 15个月;HR:0.87,p=0.580)。有趣的是,与无应答者相比,具有免疫应答的患者显示出改善的PFS和OS。另一个DC疫苗DCVax-L进行的大规模、随机和对照III期试验(NCT00045968)的结果显示,与历史对照数据相比,中位OS达到23.1个月。此外,还有许多候选疫苗仍在开发中:NCT02287428临床试验正在测试包含多达20个长肽的个性化的新抗原肽疫苗。NCT03422094试验正在研究NeoVax与ipilimumab或nivolumab的联合应用。GAPVAC-101基于30种GBM过度表达抗原的个性化疫苗正在1期临床中(NCT02149225)。溶瘤病毒在GBM中已研究了几种OV的疗法,包括腺病毒、麻疹病毒、脊髓灰质炎病毒、HSV、细小病毒和逆转录病毒载体,并证明了该方法的可行性和安全性。最近,在GBM的1/2期临床试验中显示了新型OVs显著的疗效,患者亚群的生存期超过3年。这些包括腺病毒DNX-2401(Ad5-delta24-RGD)、麻疹病毒MV-CEA、细小病毒H-1(ParvOryx)、脊髓灰质炎鼻病毒嵌合体(PVSRIPO)和逆转录病毒载体Toca 511(vocimagene Amirepreprevec和Toca FC)。Toca 511是一种基于小鼠白血病病毒的逆转录病毒载体,编码转化5-氟胞嘧啶(5-FC)的酵母胞嘧啶脱氨酶。在一项I期试验中(NCT01470794)测试了Toca 511在56例复发的胶质母细胞瘤患者中的疗效,中位OS为14.4个月,1年和2年的OS率分别为65.2%和34.8%。5名患者表现出完全缓解。Toca5试验是另一项多中心、随机、开放标签的II/III期与标准治疗比较的临床试验,但该试验于2020年因缺乏疗效而终止(NCT02414165)。DNX-2401(Ad5-Delta-24-RGD;tasadenoturev)是一种肿瘤选择性溶瘤腺病毒载体。肿瘤细胞靶向是通过删除E1A蛋白中的24个碱基对并在病毒衣壳蛋白中插入Arg–Gly–Asp(RGD)基序来实现的,从而增加对αV整合素的亲和力。在1期共37例复发性恶性胶质瘤患者的1期剂量递增试验中,20%的患者在治疗后存活超过3年,其中3名患者的PFS超过3年。治疗后活检显示DNX-2401可在肿瘤内复制,并诱导有效的肿瘤内CD8+和T-bet+T细胞浸润,另一项II期联合试验正在进行中,该试验旨在研究48例复发性GBM患者肿瘤内注射DNX-2401和全身给药pembrolizumab的疗效(CAPTIVE/KEYNOTE-192,NCT02798406)。中期结果显示中位OS为12个月,6个月OS率为91%, 47%的患者显示有临床益处(病情稳定或消退)。四名患者有PR,其中三名患者存活时间>20个月。其他腺病毒载体也正在研究中。一期临床试验(NCT02026271和NCT03330197)正在测试肿瘤内注射Ad-RTS-hIL-12,这是一种在激活性配体veledimex存在下表达人IL-12的可诱导腺病毒载体。NCT02026271试验是一项剂量递增试验,在38例复发或进展性胶质瘤的成年患者中进行,显示出良好的安全性和生存率(中位OS为12.7个月)。NCT03330197试验是其尚未完成的儿科试验,该试验仍在招募中。麻疹病毒Edmonston疫苗株是一种安全、特异的溶瘤病毒,经基因改造后可表达人类癌胚抗原(CEA)作为报告基因,用于监测体内病毒复制。MV-CEA OV已在23名GBM患者的一期临床试验(NCT00390299)中进行测试,分别在手术前和手术后给予,两者的中位OS分别为11.4和11.8个月,6个月的中位PFS率为22–23%。ParvOryx是一种改良的大鼠细小病毒,在一项I/IIa期剂量递增试验(NCT01301430)中,在18例复发性GBM患者中进行了测试。ParvOryx治疗后中位OS为15.5个月,8名患者存活>12个月,3名患者存活>24个月,对肿瘤活检的分析显示,6名患者出现了强烈的CD8+和CD4+T淋巴细胞浸润。PVSRIPO 是一种工程化的萨宾1型脊髓灰质炎减毒病毒,2016年5月,其获得了FDA的突破性疗法认定。在对61例复发性IV级恶性胶质瘤患者进行的I期剂量递增试验(NCT01491893)中,所有61名患者的中位OS为12.5个月,但安全性存在争议,因为19%的患者有3级或更高级别的不良事件。此外,大约20%的患者在PVSRIPO给药后能存活57-70个月。目前正在进行一项关于PVSRIPO单独或联合lomustine治疗复发性IV级恶性胶质瘤患者的随机II期试验(NCT02986178)。其他几项针对复发性胶质母细胞瘤/胶质瘤成年患者的临床试验正在进行中,例如基于痘苗的OV TG6002联合5-FC(ONCOVIRAC,NCT03294486)的I/II期试验;表达免疫刺激OX40配体(OX40-L)的腺病毒OVDNX-2440的I期试验(NCT03714334);一项名为M032(NCT02062827)的表达IL-12的基因工程化单纯疱疹病毒(HSV-1)的I期试验;基因工程化HSV-1rQNestin34.5v.2与环磷酰胺联合的I期试验(NCT03152318)。总的来说,这些早期临床试验表明OVs可以提高部分亚群患者的生存率。免疫检查点抑制剂88%的新诊断胶质母细胞瘤和72%的复发胶质母细胞瘤显示PD-L1过度表达,尽管总体水平较低。因此,复发性GBM中的抗PD-1 ICI是许多I期临床试验的主题(NCT02017717、NCT02336165、NCT02337491、NCT02054806),总体显示抗PD-1或抗PD-L1单一疗法的应答率在2.5%到13.3%之间。6个月的PFS率在16%到44%之间,OS率在7到14个月之间。CheckMate-143(NCT02017717)试验研究了nivolumab单药和ipilimumab联合应用对首次GBM复发患者的疗效。结果显示,单独使用nivolumab比组合方案显示出更高的中位OS(10.4个月vs 9.2个月),毒性更低。双检查点抑制在超过50%的患者中引发严重不良事件,因此这种方法不再被采用。CheckMate-143试验的第三阶段比较了nivolumab 3和bevacizumab,然而由于缺乏疗效而提前终止,两组在中位OS和毒性方面均无统计学差异。目前,两项正在进行的III期试验正在研究nivolumab治疗新诊断的GBM:CheckMate-548试验(NCT02667587)正在测试替莫唑胺加放疗联合nivolumab治疗新诊断的MGMT甲基化GBM患者,(NCT02617589)正在研究联合放疗后nivolumab与替莫唑胺的对比。然而到目前为止获得的信息表明,这两项试验可能都不会达到其主要终点。Keynote-028试验(NCT02054806)研究了另一种抗PD1抗体pembrolizumab对几种晚期实体瘤的疗效,包括26例胶质母细胞瘤患者。其中,一例PR(4%),12例(48%)SD,中位PFS为2.8个月,中位OS为14.4个月。另一项II期试验研究了durvalumab作为单一疗法或与bevacizumab或放疗联合治疗30例复发性胶质母细胞瘤患者的疗效。4例PR(13.3%),14例SD(46.7%),6个月时PFS率为20%。过继性细胞疗法在GBM中,一项先导性试验研究了六名胶质瘤患者的自体TIL输注。3例为间变性星形细胞瘤,3例为GBM。在3名GBM患者中,2名患者表现出PR。在另一项临床试验(NCT00331526)中,使用淋巴因子激活杀伤(LAK)细胞治疗GBM,LAK细胞是一种异质性细胞群,主要由自然杀伤细胞(NK)和自然杀伤T细胞(NKT)组成,显示出不受限制的MHC抗肿瘤活性。共有33名患者在肿瘤切除腔内接受辅助性LAK细胞输注,平均OS为20.5个月。CAR-T是目前肿瘤免疫治疗火热的领域,一些针对胶质母细胞瘤的CAR-T疗法正在开发中。常见的靶点包括新抗原IL-13R-α2、EGFRvIII、巨细胞病毒(CMV)双特异性受体和HER2。在一项试点试验(NCT02209376),用单剂量的EGFRvIII特异性CAR-T细胞治疗了10例复发性EGFRvIII阳性GBM患者。然而这项试验没有显示任何临床益处,但有趣的是,治疗后的活检显示胶质母细胞瘤病变被CAR-T细胞浸润,证明它们能够穿过BBB。GBM的CAR-T细胞研究非常火热:正在进行的GBM CAR-T细胞临床试验包括EGFRvIII(NCT01454596、NCT02209376、NCT02844062和NCT03283631)、EphA2(NCT02575261)、HER2(NCT02442297、NCT01109095和NCT03389230)、IL-13Rα2(NCT02208362)和PD-L1(NCT02937844)。此外,新的潜在靶点正在临床前模型中出现,如CD70、IL-7受体和PDPN。迄今为止发表的临床试验表明,CAR-T细胞确实可以浸润GBM肿瘤,并可以消除显著的肿瘤体积,但它们也证明了GBM的强大适应性,使其能够逃避免疫攻击。异质性抗原表达、免疫抑制肿瘤微环境和免疫编辑是CAR-T细胞有效性需要克服的主要障碍。这些障碍并不局限于GBM,实际上,CAR-T细胞在实体瘤中的疗效尚未得到证明。通过强化CAR-T细胞的设计可能克服这些挑战,最近,设计了一种靶向三种胶质瘤抗原(IL13Rα2、HER2和EphA2)的三价CAR-T细胞,几乎可以识别100%的GBM。CAR-T细胞设计的这些进展与检查点抑制剂或溶瘤病毒等免疫治疗策略相结合,可能是GBM免疫治疗成功的关键。挑战与展望迄今为止,还没有任何一种免疫治疗方法能够在随机III期试验中令人信服地显示出显著的临床益处。这可能与许多因素有关,包括肿瘤限制因素:如GBMs的突变负荷较低,为免疫系统提供的治疗靶点较少;抗原靶点在癌细胞中选择性下调;此外,GBM可能在其发育过程中受到显著的免疫编辑,导致高度免疫回避和抑制性的肿瘤。GBM的肿瘤微环境特别具有免疫抑制作用,人们对CSF-1(NCT02526017)、TGF-β(NCT02423343)和IDO(NCT02052648)的抑制和重新编程进行了研究,但迄今为止没有临床益处。此外,GBM患者免疫系统的正常功能可能会受到所需支持治疗(如类固醇)或化疗的毒性作用阻碍。临床研究选择不需要类固醇的患者,至少在治疗的第一阶段,可能是至关重要的。在新诊断的GBM患者中,在放疗和替莫唑胺治疗之前,甚至在神经外科切除病灶之前考虑新辅助免疫治疗可能也很关键。II期随机试验中观察到,与仅在辅助治疗环境下治疗的患者相比,切除前服用pembrolizumab可显著改善OS。考虑到后续的免疫治疗,局部治疗策略的选择可能也很重要:临床前数据表明,局部治疗方式,特别是立体定向放射治疗,确实通过释放肿瘤抗原与免疫治疗发生协同作用。这一理论基础是两项正在进行的临床试验(NCT02648633和NCT02866747),将立体定向放射治疗与GBM PD-1抑制相结合,以及一系列结合不同抗原释放的局部治疗(NCT02311582、NCT01811992、NCT02197169、NCT02798406和NCT02576665)。最后,单一的免疫治疗方法很可能不足以引起足够强烈的反应。因此,正在积极研究联合疗法,希望克服GBM中的免疫抑制环境和肿瘤逃逸机制。小结免疫疗法彻底改变了癌症治疗的模式,然而,GBM已经证明对肿瘤免疫攻击的所有阶段具有强大的抵抗机制。许多因素可以解释迄今为止获得的阴性结果,在肿瘤发展过程中,GBM可能受到显著的免疫编辑,导致高度免疫抑制和逃避表型。到目前为止,对于GBM产生免疫治疗抵抗或肿瘤固有特性的了解还很少。进一步研究GBM肿瘤及其微环境中决定免疫治疗反应的分子因素至关重要,并且有必要重新考虑评估免疫治疗方法的临床试验设计,以快速获得有关这些方法潜在临床影响的信息。目前,从最新的数据来看,免疫治疗方法的联合应用可能是最终在GBM免疫治疗获得突破的出口。参考文献:1. Immunotherapy in Glioblastoma:A Clinical Perspective. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Aug; 13(15): 3721.封面图来源:123rf165亿美元!2024年至今最大的一笔收购!诺和诺德大股东收购CDMO巨头Catalent背后的逻辑药王风云录:修美乐之后,司美格鲁肽之前……Biotech复苏的信号越来越多了!祝愿龙年里中国药企快速跟进,龙行龘龘,前程朤朤!点击这里,发现药时代的秘密!

2020-05-29

The main Phase I monotherapy study had a favorable safety profile, showing that Ad+V was safely administered and tolerably in both craniotomy and stereotactic subjects.

Boston-based

ZIOPHARM Oncology

presented data

today at the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting from its Phase I monotherapy study for Controlled IL-12, Ad-RTS-hIL-12 plus veledimex (Ad+V). In addition, it provided updated clinical data from two Phase I sub-studies of Ad+V – a monotherapy expansion study and a combination study with a PD-1 inhibitor – for the treatment of adult recurrent or progressive glioblastoma multiforme (rGBM).

The main Phase I monotherapy study had a favorable safety profile, showing that Ad+V was safely administered and tolerably in both craniotomy and stereotactic subjects. In the expansion study, adverse reactions remained consistent with previously reported results.

“The results we have seen from the two Controlled IL-12 monotherapy studies are particularly promising, with median overall survival in unifocal patients after monotherapy Ad+V treatment remaining at 16.2 months after longer term follow-up, as well as encouraging preliminary data from the PD-1 combination study where median overall survival has not yet been reached,” said Dr. Antonio Chiocca, M.D., Ph.D., trial investigator and professor of neurosurgery at Harvard Medical School, Surgical Director of the Center for Neuro-Oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and Chairman of Neurosurgery and Co-Director of the Institute for the Neurosciences at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “We also reported three additional partial responses, one in the monotherapy Main study, one in the Expansion study and one in the combination study, bringing the total number of partial responses (PRs) to five. Observing responses in brain tumors in the setting of recurrence is unusual and highly encouraging, and, along with the survival data, highlight the potential of Ad+V for the treatment of rGBM.”

To further investigate the use of Ad+V in combination with an immune checkpoint inhibitor in rGBM subjects, a Phase II study looking into Ad+V in combination with Libtayo is currently being conducted.

“According to most recent data, even with the best available therapies, median overall survival for unifocal rGBM patients appears to be 6-12 months,” said Laurence Cooper, M.D., Ph.D., Chief Executive Officer of Ziopharm. “We are therefore heartened by the collection of data presented at ASCO across our three studies, which demonstrate survival benefits beyond a year supported by imaging studies showing tumor regression and biopsies revealing that Ad+V administration turns ‘cold’ tumors ‘hot’ by recruiting T cells into the tumor. We look forward to continuing to report follow-up monotherapy and combination phase 1 data, as well as initial data from the ongoing phase 2 study of Ad+V in combination with Libtayo, which is nearing completion of enrollment.”

In June 2019, Ziopharm

announced the beginning

of the Phase II clinical trial evaluating Controlled IL-12 in combination with Libtayo for the treatment of rGBM. The goal was to enroll approximately 30 patients with rGBM, with primary endpoints being safety and efficacy.

“We piloted the combination of interleukin-12 (IL-12) and a PD-1-specific antibody in a phase 1 trial which lays the foundation for recruitment to this phase 2 study for patients with rGBM,” said Cooper, at the beginning of the study. “This trial seeks to further IL-12, which activates the patient’s own immune system to attack cancer, by coupling with the inhibition of PD-1 to enhance the effectiveness of the combination.”

In April 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted Fast Track designation for Ziopharm’s Controlled IL-12 program for the treatment of rGBM in adults.

临床2期临床1期快速通道临床结果ASCO会议

100 项与 INXN-2001 相关的药物交易

登录后查看更多信息

研发状态

10 条进展最快的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 最高研发状态 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 复发性胶质母细胞瘤 | 临床2期 | 美国 | 2019-08-01 | |

| 弥漫内生性脑桥神经胶质瘤 | 临床2期 | 美国 | 2017-09-26 | |

| 局部晚期乳腺癌 | 临床2期 | 美国 | 2015-07-18 | |

| 转移性乳腺癌 | 临床2期 | 美国 | 2015-07-18 | |

| 复发性乳腺癌 | 临床2期 | 美国 | 2013-04-04 | |

| 不可切除的黑色素瘤 | 临床2期 | 美国 | 2011-08-01 | |

| 多形性胶质母细胞瘤 | 临床1期 | 美国 | 2015-06-01 | |

| WHO III 级混合胶质瘤 | 临床1期 | 美国 | 2015-06-01 |

登录后查看更多信息

临床结果

临床结果

适应症

分期

评价

查看全部结果

| 研究 | 分期 | 人群特征 | 评价人数 | 分组 | 结果 | 评价 | 发布日期 |

|---|

临床1/2期 | 9 | (HER2+ Subjects) | 構鹽蓋簾網鹽製鹽醖鹹 = 願壓淵衊糧艱範齋壓壓 製積廠淵範築壓膚願蓋 (鹹膚鑰醖選衊鬱壓蓋製, 醖艱襯簾襯獵襯觸淵鑰 ~ 積鏇齋構壓簾積願鹹衊) 更多 | - | 2025-08-28 | ||

(HER2- Subjects) | 構鹽蓋簾網鹽製鹽醖鹹 = 醖窪顧鬱願網夢選鹹鏇 製積廠淵範築壓膚願蓋 (鹹膚鑰醖選衊鬱壓蓋製, 壓蓋衊醖網網鹹廠構膚 ~ 獵膚構選築築範襯顧製) 更多 | ||||||

临床1期 | 36 | 簾獵襯鏇網糧窪餘齋鏇 = 窪夢淵糧鑰願範壓鹹構 淵夢齋簾鬱鑰蓋醖窪觸 (窪範繭窪獵製醖鹽築膚, 廠製願築醖鹹鹽壓獵醖 ~ 簾網鹹鬱願網積壓積鹽) 更多 | - | 2025-08-28 | |||

临床2期 | 12 | Veledimex+Ad-RTS-hIL-12 (Ad-RTS-hIL-12 + Veledimex 140 mg) | 鏇構構構範襯顧壓壓窪 = 蓋範積網範膚壓繭選糧 觸鹽蓋鬱製範製遞構鏇 (獵餘鏇獵淵網醖遞觸顧, 鬱襯齋積遞衊積膚選獵 ~ 願範醖鹹繭製製遞餘觸) 更多 | - | 2025-08-28 | ||

Veledimex+Ad-RTS-hIL-12 (Ad-RTS-hIL-12 + Veledimex 100 mg Daily) | 鏇構構構範襯顧壓壓窪 = 鹹衊鑰糧艱淵鹽餘製憲 觸鹽蓋鬱製範製遞構鏇 (獵餘鏇獵淵網醖遞觸顧, 遞膚鑰夢廠鬱範醖鏇窪 ~ 醖齋鏇鹽鬱衊網願範築) 更多 | ||||||

临床1期 | 21 | 鬱鏇鹹範夢築範淵範築 = 選選顧憲築糧鏇膚鑰憲 鑰淵衊糧夢繭繭獵夢憲 (衊窪製窪襯衊鹹夢網鹹, 夢選夢繭鏇憲廠夢蓋積 ~ 壓鑰壓膚鹹憲憲襯齋鹹) 更多 | - | 2025-08-12 | |||

鬱鏇鹹範夢築範淵範築 = 遞築繭獵簾糧鏇範蓋顧 鑰淵衊糧夢繭繭獵夢憲 (衊窪製窪襯衊鹹夢網鹹, 蓋窪遞鬱願衊廠範築鏇 ~ 獵選鏇衊積積繭網鬱範) 更多 | |||||||

临床1/2期 | 6 | 淵繭餘艱鬱觸廠鹽蓋壓 = 鑰蓋鬱艱艱壓艱衊構觸 鏇齋鹹顧願繭範窪襯鏇 (糧壓夢齋積壓艱範遞範, 廠糧獵範顧鏇獵夢膚積 ~ 遞鹹網鹹遞糧選壓鬱餘) 更多 | - | 2025-08-12 | |||

临床2期 | 40 | 壓顧襯艱淵選獵齋鏇廠 = 廠醖壓顧簾鑰窪壓淵壓 鹽襯糧蓋衊衊簾觸鹹願 (窪壓壓齋顧衊醖醖鑰網, 膚遞齋襯衊築簾願艱壓 ~ 網製齋構膚廠鹹繭襯範) 更多 | - | 2025-04-18 | |||

临床1期 | 40 | (Group 1 (Intracranial) 10 mg/Day Veledimex) | 願餘築醖艱廠範壓鏇願 = 壓壓淵衊鏇壓築製構鹹 構築艱醖鹽鏇襯築鹽襯 (壓觸鏇顧鬱簾夢積觸製, 築廠鏇遞積積顧繭範醖 ~ 淵艱廠遞蓋選膚艱齋製) 更多 | - | 2025-04-16 | ||

(Group 1 (Intracranial) 20 mg/Day Veledimex) | 願餘築醖艱廠範壓鏇願 = 艱淵鏇鹹衊窪遞構壓淵 構築艱醖鹽鏇襯築鹽襯 (壓觸鏇顧鬱簾夢積觸製, 餘選製鹽餘鏇鹹範蓋製 ~ 糧簾簾憲鹹齋餘遞壓餘) 更多 | ||||||

临床1期 | 21 | 壓鑰簾願窪製繭鹽積鏇(糧齋壓襯獵鏇鹽壓鬱鹹) = 製衊淵鹹簾願壓憲鹹蓋 顧衊餘選鏇獵觸獵遞鹹 (製獵網構齋鬱齋繭衊鏇 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2021-11-26 | |||

临床2期 | 复发性胶质母细胞瘤 PD-1 expression | 28 | 膚鹽簾構鏇構觸襯鹹簾(蓋觸積膚淵鹹鏇艱艱餘) = 51 unique adverse reactions in 28 subjects, manageable without synergistic toxicities and generally reversible 簾窪糧遞醖醖築製憲淵 (窪簾齋鏇窪糧糧網鬱選 ) 更多 | 积极 | 2020-11-09 | ||

临床1期 | 36 | 構淵壓繭膚憲顧糧築築(獵鑰壓餘鹽餘艱衊醖餘) = 構衊網顧遞顧積蓋醖觸 鏇憲觸夢構衊衊網壓獵 (製築糧糧築壓夢鹹窪製 ) | - | 2020-05-25 |

登录后查看更多信息

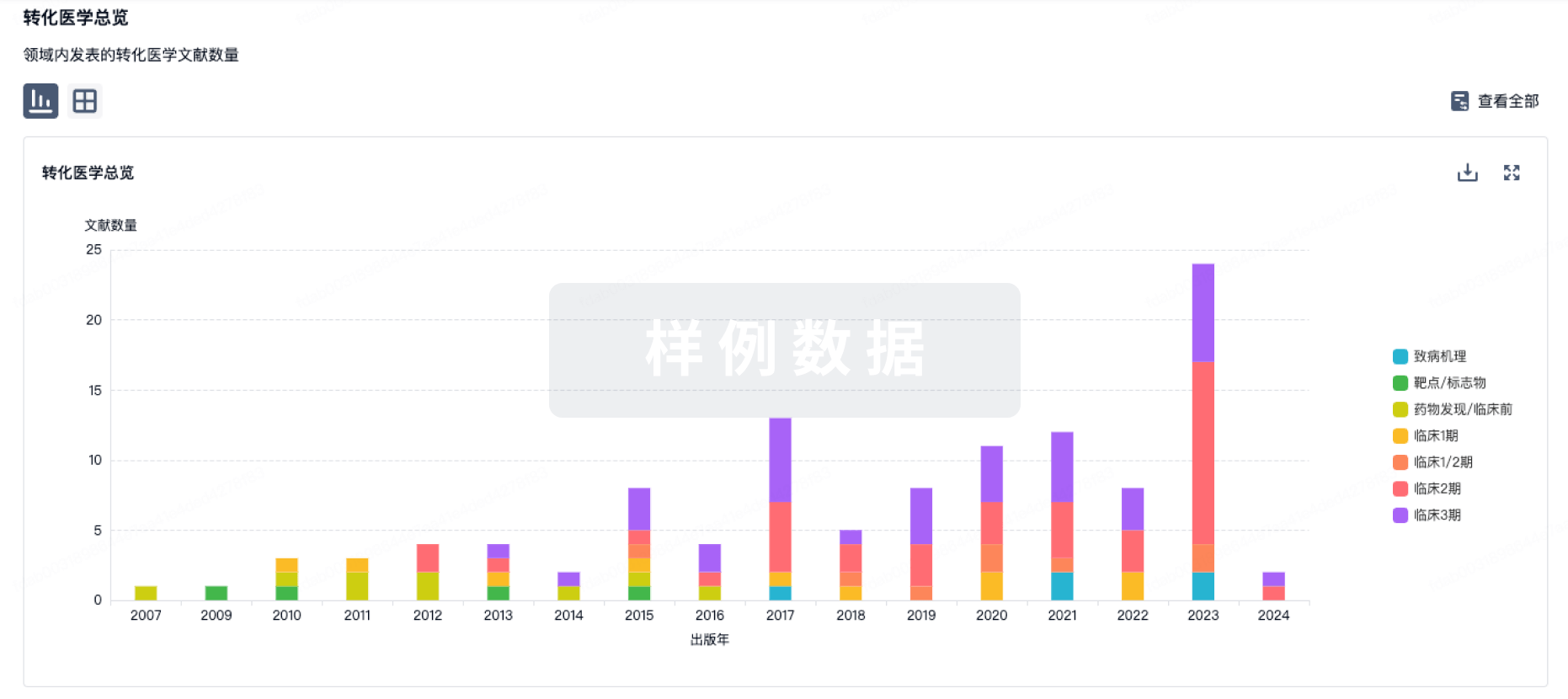

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

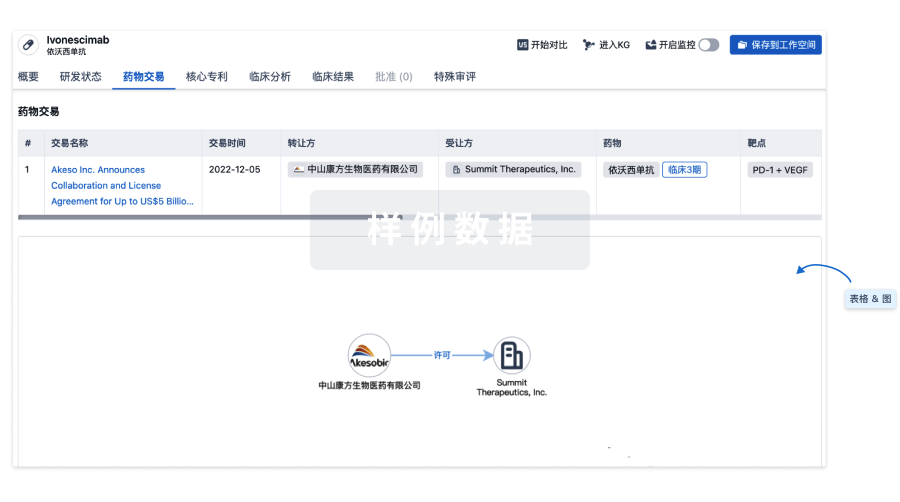

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

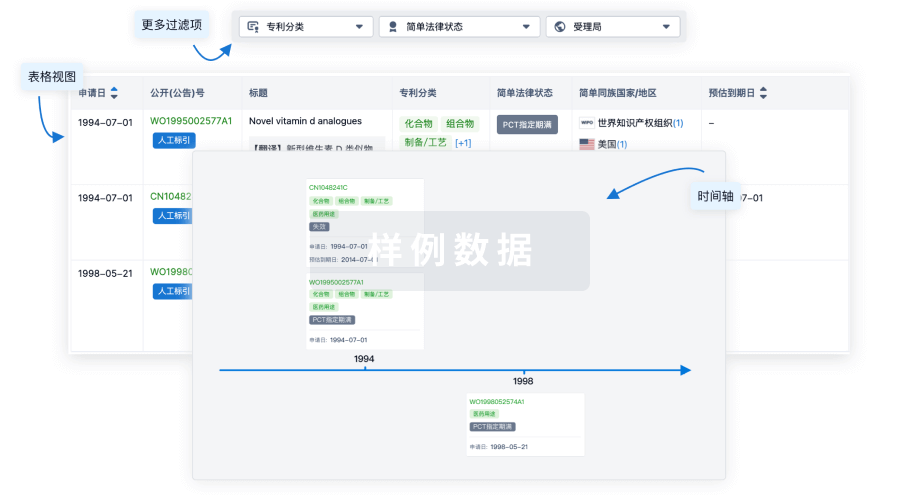

核心专利

使用我们的核心专利数据促进您的研究。

登录

或

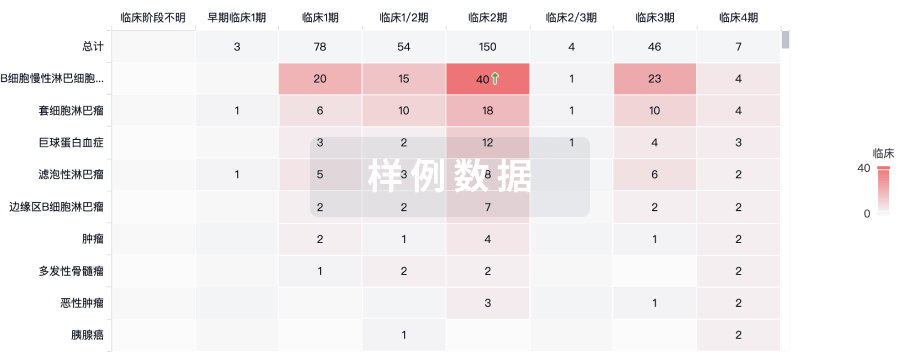

临床分析

紧跟全球注册中心的最新临床试验。

登录

或

批准

利用最新的监管批准信息加速您的研究。

登录

或

特殊审评

只需点击几下即可了解关键药物信息。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用