预约演示

更新于:2025-05-07

GHSR x ghrelin

更新于:2025-05-07

关联

1

项与 GHSR x ghrelin 相关的药物作用机制 GHSR激动剂 [+1] |

在研机构- |

在研适应症- |

最高研发阶段无进展 |

首次获批国家/地区- |

首次获批日期1800-01-20 |

100 项与 GHSR x ghrelin 相关的临床结果

登录后查看更多信息

100 项与 GHSR x ghrelin 相关的转化医学

登录后查看更多信息

0 项与 GHSR x ghrelin 相关的专利(医药)

登录后查看更多信息

1,716

项与 GHSR x ghrelin 相关的文献(医药)2025-07-01·Psychoneuroendocrinology

Altered circadian pattern of activity in a chronic activity-based anorexia nervosa-like female mouse model deficient for GHSR

Article

作者: Tolle, Virginie ; Mattioni, Julia ; Lebrun, Nicolas ; Gorwood, Philip ; Aïdat, Sana ; Bohlooly-Y, Mohammad ; Viltart, Odile ; Duriez, Philibert

2025-05-01·Drug and Alcohol Dependence

Environmental enrichment attenuates reinstatement of heroin seeking and reverses heroin-induced upregulation of mesolimbic ghrelin receptors

Article

作者: Galaj, Ewa ; Ranaldi, Robert ; Vinod, Sneha ; Gubin, Sami ; Nachshon, Ziv ; Vashisht, Apoorva ; You, Zhi-Bing ; Sandoval, Natalie ; Corso, Elizabeth ; Slama, Joseph ; Freund, Matthew ; Gacso, Zuzu ; Adamson, George

2025-04-22·The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism

Loss-of-Function GHSR Variants Are Associated With Short Stature and Low IGF-I

Article

作者: Woltering, M Claire ; Kruijsen, Anne R ; Wit, Jan M ; de Groote, Kirsten ; Joustra, Sjoerd D ; Heijligers, Malou ; Rensen, Patrick C N ; Visser, Jenny A ; de Bruin, Christiaan ; Yue, Kaiming ; Bannink, Ellen M N ; de Waal, Wouter J ; Boot, Annemiek M ; Delemarre, Lucia C ; Bakker-van Waarde, Willie M ; van der Kaay, Daniëlle C M ; Losekoot, Monique ; van Tellingen, Vera ; Punt, Lauren D ; van Boekholt, Anneke A ; van der Heyden, Josine C ; Hannema, Sabine E ; Delhanty, Patric J D ; Rinne, Tuula ; Mutsters, Noa J M ; Kooijman, Sander ; van den Akker, Erica L T ; van Nieuwaal-van Maren, Nancy H G ; van Duyvenvoorde, Hermine A

4

项与 GHSR x ghrelin 相关的新闻(医药)2024-09-17

BARCELONA —

One of this weekend’s sleeper data presentations at Europe’s biggest oncology conference puts Pfizer in a leading position in a common cancer condition with no approved treatments in the US or Europe.

The New York-based pharma giant’s GDF-15-directed monoclonal antibody

helped cancer patients gain weight

and, at the highest dose, experience improvements in appetite, physical activity and muscle mass in a

Phase 2

trial, according to data presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology confab on Saturday.

Analysts at Leerink Partners think the experimental medicine, code-named ponsegromab, has blockbuster potential.

But the large pharma has many questions to work through before it can mount a registrational study next year for ponsegromab in cancer cachexia, a muscle-wasting condition that leads to severe weight loss and impacts a patient’s ability to tolerate cancer medications. Patients with cachexia also require more healthcare resources, leading to a “high clinical and economic burden,” according to another Pfizer-funded study

presented

at ESMO.

Doctors have long sought a treatment for the metabolic condition, which some research suggests may be linked to up to

30%

of cancer deaths. It’s also a strain on patients with chronic conditions like heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, among others. The broad potential gives ponsegromab a shot at achieving sales of $1 billion or more, Leerink Partners analyst David Risinger wrote in a Sunday evening note.

Despite its prevalence, though, the condition has not received “the attention it deserves,” Min Li, a professor and co-leader of the cancer biology program at the Stephenson Cancer Center in Oklahoma, said in an email.

“We are now more confident in saying that we can see the light at the end of the tunnel,” Li said in the days after the ESMO presentation and simultaneous publication of the Phase 2 data in the

New England Journal of Medicine

.

Having one of the world’s biggest pharma companies with ample R&D resources to approach late-stage testing could be a boon for the field.

“Incredible progress is finally being made in this space, and we very much hope that Pfizer’s findings continue to be positive and pave the way for more successful trials to follow,” Andy Judge, a University of Florida professor and president of the Cancer Cachexia Society, told Endpoints in an email.

Cachexia comes with a lot of complexities, likely leading to a challenging Phase 3 showdown for Pfizer. The company anticipates launching the trial next year and it still needs to hash out plans with regulators, according to a spokesperson, who said Pfizer will share more Phase 3 details at a later date.

The condition is quite heterogeneous and impacts different cancers at varying rates, which could make it difficult to prove a treatment works in late-stage trials.

Li noted that “there is no consensus on the optimal endpoint to evaluate cancer cachexia.”

Another biotech, NGM Bio,

warned

in recent years of the lack of a clear regulatory path for cachexia. Another company received

approval

in Japan in 2020 for the medicine anamorelin, but the ghrelin receptor agonist was

rejected

in Europe a few years before.

Also standing in the way is the number of organs and tissues involved in the systemic dysfunction. Going after a single pathway “has yielded limited efficacy,” Li said.

Pfizer’s ponsegromab goes after growth differentiation factor 15, or GDF-15. The company’s researchers have

said

neutralizing GDF-15 could lead to improvements in caloric intake and boost physical activity. The candidate was discovered in-house and first entered the clinic

in a 2018

healthy volunteer trial.

Ponsegromab is also being tested in

patients with heart failure

. That study is enrolling patients with cardiac cachexia or fatigue in its main cohort and is expected to be completed next March, according to the federal trials database.

Li noted other potential pathways in cancer cachexia could be targeted, such as “myostatin/activin signaling, IL-6, ghrelin, circular RNAs, metabolic enzymes, TNF and TGF.”

Meanwhile, more studies are needed to “directly prove” that stabilizing muscle and fat reserves, “or even revers[ing] those losses,” has a direct impact on patient outcomes, Michael Rosenthal, assistant director of radiology at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said in an email.

Aside from the effects on weight, doctors will look for impacts on daily activities. “It would be impressive to see improvement in ECOG performance status and overall survival in a randomized trial of chemotherapy with or without ponsegromab,” Vincent Chung, a medical oncologist at City of Hope, said in an email. ECOG is a

scale

that assesses a patient’s ability to function, including walking and self-care activities.

Pfizer is in the lead in cachexia drug development, and it’s no stranger to breaking open fields, having done so in areas like ATTR-CM, where it could soon face competition.

Other drugmakers looking at cachexia include UK-based

Actimed

Therapeutics, Tokyo-based

TMS

and Vistagen, which

says

on its website that it is “evaluating the path forward” for its candidate for more Phase 2 development.

Even if those medicines make it to market, it’s still important to think about treating cachexia in a “multi-dimensional way, rather than a single drug,” David Hui, director of supportive and palliative care research at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, said in an interview on the sidelines of ESMO.

Doctors currently work with a team of healthcare professionals to address cachexia with diet and exercise and medications to treat symptoms of pain, difficulty swallowing and other complications, he said.

“Having the dietitian, physical therapy and supportive palliative care team working side by side together with the patient and family can, hopefully, lead to improved outcomes because everyone may have different concerns related to cachexia,” Hui said.

临床2期上市批准临床3期

2024-07-10

This article will continue to review the antitumor targets of the GPCR family and the therapeutic drugs that have been marketed.

07 GPRC5DGPRC5D is a Class C type-7 transmembrane GPCR receptor protein, primarily expressed in cells with a plasma cell phenotype, including the majority of malignant plasma cells from patients with multiple myeloma (MM). GPRC5D is an orphan receptor, whose ligand and signaling mechanisms have yet to be identified. In patients with multiple myeloma, the expression levels of GPRC5D messenger RNA correlate with the plasma cell burden and genetic abnormalities such as Rb-1 deletion and high-risk MM. Compared to normal cells, GPRC5D mRNA levels are higher in myeloma plasma cells. The selective expression of GPRC5D suggests that it could be a potential target for effector cell-mediated therapy in treating plasma cell disorders like MM.

The accompanying figure shows the expression differences of GPRC5A in normal tissues versus various tumor tissues.

Talquetamab is a full-length, humanized IgG4 bispecific antibody developed by Janssen Pharmaceuticals that targets GPRC5D and the CD3 receptor. It is the first GPRC5D-targeting agent approved for the treatment of triple-exposed relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma patients and was approved for use in the United States in August 2023. Bispecific antibodies are designed to overcome some of the limitations of traditional monoclonal antibodies and enhance therapeutic efficacy. T-cell-engaging bispecific antibodies have two antigen-binding sites: one for CD3 on the surface of T-cells and another for a target antigen expressed on tumor cells. The simultaneous binding to T-cell surface receptors and tumor-specific antigens brings T cells into proximity with tumor cells, leading to synapse formation, activation of T cells, and subsequent killing of malignant cells. T-cell-engaged antibodies may overcome certain forms of tumor-mediated immune evasion since they do not require antigens to be presented by major histocompatibility complex molecules, which are often downregulated or lost in tumor cells, to perform their effector functions.

08 GHSRGhrelin is a small peptide consisting of 28 amino acids, identified as a ligand for the growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR). Beyond its original function in stimulating the release of growth hormone from the pituitary, ghrelin has various roles, including regulating energy balance, gastric acid secretion, appetite, insulin secretion, gastrointestinal motility, and the renewal of gastric and intestinal mucosa.

Cachexia is a hypercatabolic state characterized by accelerated loss of skeletal muscle in the presence of chronic inflammatory response, seen in conditions such as advanced cancer, chronic infections, AIDS, heart failure, rheumatoid arthritis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cachexia is prevalent in various malignancies, affecting nearly half of patients with advanced cancer. Although cancer patients commonly experience decreased appetite and weight loss, the significant weight loss in cachexia cannot be solely attributed to inadequate caloric intake. Insufficient oral intake combined with complex metabolic abnormalities can lead to increased basal energy expenditure, ultimately resulting in the reduction of lean body mass due to skeletal muscle consumption. Unlike simple starvation, where caloric deficiency can be reversed by appropriate feeding, weight loss in cachexia cannot be adequately treated through aggressive nutritional support.

Anamorelin, developed by Helsinn Healthcare SA, is an orally administered non-peptidic drug, a selective agonist for the growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR). It has effects on promoting appetite and anabolic metabolism, primarily used in treating cancer cachexia and anorexia. The drug was approved for market in Japan in 2021.

Anamorelin acts by stimulating the levels of growth hormone (GH), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3) in the human body, without affecting the plasma levels of other hormones such as prolactin, cortisol, insulin, glucose, adrenocorticotropic hormone, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, or thyroid-stimulating hormone. It is capable of increasing appetite, overall body weight, lean body mass, and muscle strength.

However, on May 18, 2017, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended the refusal of the marketing authorization for the drug, because although Anamorelin had a slight effect on lean body weight in patients, it showed no proven effect on handgrip strength or patient quality of life. Additionally, following inspections of clinical research facilities, the agency considered that the safety data of the drug were not adequately documented.

Furthermore, increasing evidence also reveals ghrelin's role in regulating several processes related to cancer progression, especially regarding metastasis and proliferation. Transcriptomic data generated by RNA sequencing and matched clinical data from large cancer cohorts in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) indicate elevated expressions of GHRL and GHSR in various cancers including cholangiocarcinoma, breast cancer, endometrial carcinoma, glioblastoma, renal cancer, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, glioma, lung cancer, mesothelioma, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, sarcoma, testicular cancer, thymoma, and acute myeloid leukemia. This suggests a pathological role for these genes in cancer, making the development of selective antagonists to inhibit GHSR activity a potential anti-tumor strategy. Consequently, targeted anti-tumor research on GHSR undoubtedly requires further mechanistic studies and exploration.

How to obtain the latest research advancements in the field of biopharmaceuticals?

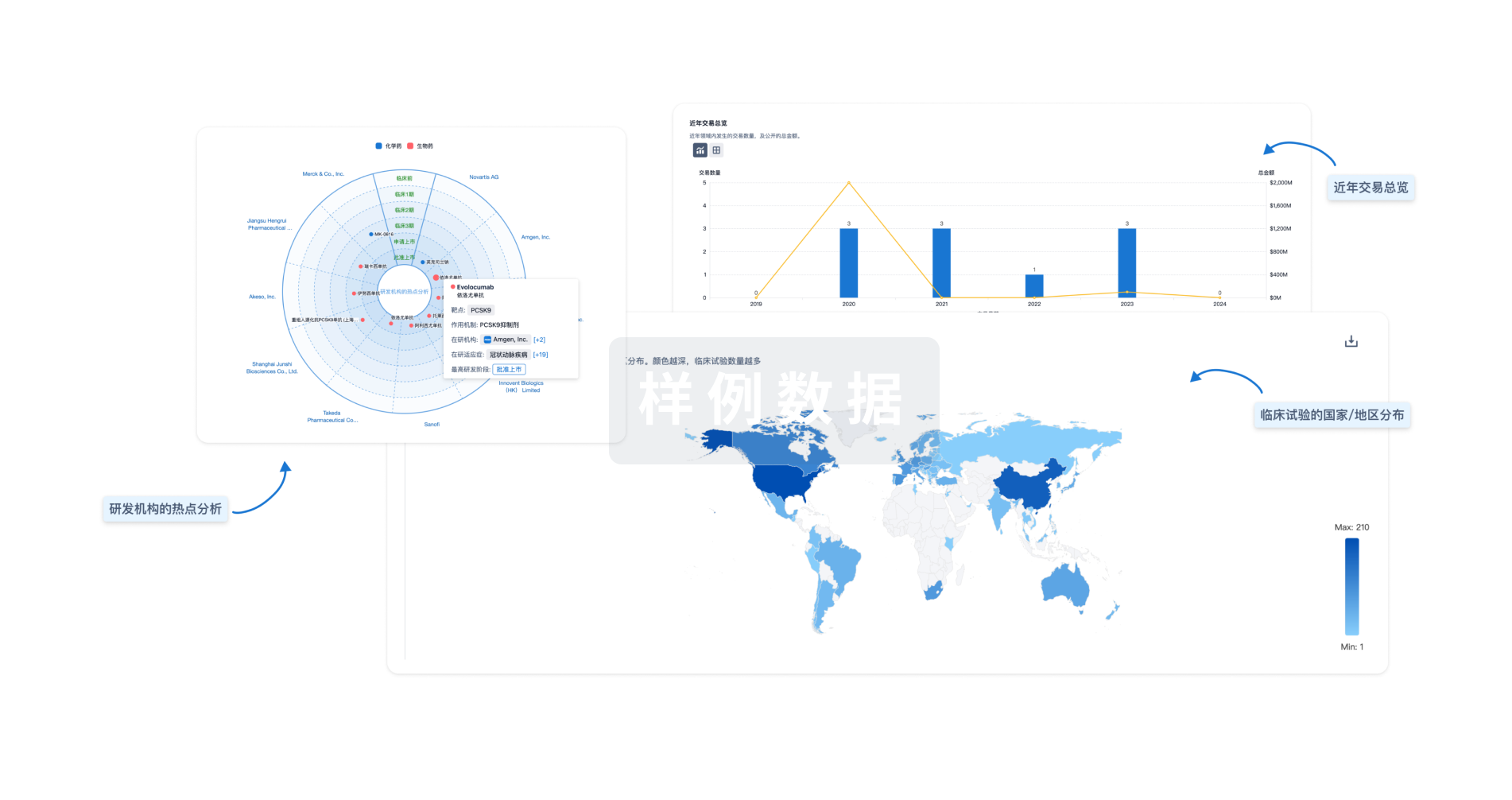

In the Synapse database, you can keep abreast of the latest research and development advances in drugs, targets, indications, organizations, etc., anywhere and anytime, on a daily or weekly basis. Click on the image below to embark on a brand new journey of drug discovery!

2024-01-18

A team of scientists has made an important discovery that could lead to a novel treatment for obesity and obesity-associated diseases or conditions.

Texas A&M AgriLife Research study may lead to novel obesity treatment New study provides insights on role of 'hunger hormone' receptor in obesity-realted chronic inflammation

A team comprised primarily of Texas A&M AgriLife Research scientists has made an important discovery that could lead to a novel treatment for obesity and obesity-associated diseases or conditions.

Details of the discovery can be found in the study "Nutrient-sensing growth hormone secretagogue receptor in macrophage programming and meta-inflammation," published in the January issue of Molecular Metabolism.

Yuxiang Sun, Ph.D., is the lead investigator on a study that could lead to a novel treatment for obesity and obesity-associated diseases or conditions. (Texas A&M AgriLife photo by Michael Miller)

"Chronic inflammation commonly associated with obesity is a key reason obese individuals often have many other chronic diseases," said Yuxiang Sun, Ph.D., professor and AgriLife Research Faculty Fellow in the Texas A&M College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Department of Nutrition and associate member of the Texas A&M Institute for Advancing Health Through Agriculture, IHA.

Sun, who served as lead investigator for the study, was among several investigators from the Department of Nutrition. Study contributions were also made by other entities in The Texas A&M University System.

Competitive funding for the study came from the National Institutes of Health. It was also supported by the IHA -- the world's first research institute to bring together precision nutrition, responsive agriculture and behavioral research to reduce diet-related chronic diseases.

About the study

The study focused on the role of one molecule involved in how our bodies deal with hunger: the growth hormone secretagogue receptor, GHSR, which mediates the effect of ghrelin, known as the "hunger hormone." Studies have shown that ghrelin promotes eating and increases fat. Ghrelin activates GHSR to increase appetite, fat accumulation and insulin resistance.

Research has shown that under normal conditions, GHSR is highly active in the brain but much less active in other tissues such as liver and fat, also referred to as adipose tissue. For this reason, most ghrelin research has focused on the brain.

"Intriguingly, in previous research, we found the complete removal of GHSR protects against diet-induced inflammation and insulin resistance in adipose tissue and the liver without affecting food intake," Sun said. "This was very puzzling because that GHSR has very low expression in fat and liver cells."

A link between obesity and the immune system

Sun and her team has made the novel observation that GHSR activity in macrophages -- a major immune cell type in tissues -- increases dramatically under the condition of obesity. In this study, Sun's team investigated whether ghrelin's effect in adipose tissues and the liver was due to the infiltration of GHSR-expressing macrophages into these tissues under the condition of obesity.

"If that was the case, this infiltration by those particular GHSR-expressing macrophages would trigger chronic inflammation and insulin resistance," Sun said.

Study results and implications

To understand the role of GHSR in macrophages, the team developed a unique animal model to selectively shut down GHSR activity in macrophages.

"Indeed, our study results showed that macrophage-specific GHSR deficiency reduces diet-induced systemic inflammation and insulin resistance," Sun said. "Remarkably, GHSR deficiency in macrophages reduced diet-induced macrophage infiltration, macrophage activation and fat deposition in adipose tissue and the liver."

In addition to their effect on diet-induced chronic inflammation, the study also demonstrated that GHSR-deficient macrophages protect against acute inflammation induced by bacterial toxins.

At a molecular level, they found GHSR programs macrophages through an insulin signaling pathway, Sun said. Basically, this study showed that macrophage GHSR controls chronic inflammation in obesity by regulating macrophage programming.

She said the study's novel results demonstrate that macrophage GHSR plays a key role in meta-inflammation by promoting macrophage infiltration and inflammatory activation.

"These exciting new findings helped to resolve a long-time mystery of GHSR in adipose tissue and the liver in obesity, by uncovering the novel immunoregulatory role of GHSR and revealing that GHSR signaling is a critical link between metabolism and immunity," Sun said.

She said the study adds a new dimension to the biology of ghrelin, and underscores that ghrelin is not only a hunger hormone, but also an important nutrient-sensor and immune regulator.

"This has profound implications for health and disease, as blocking GHSR in macrophages may serve as a promising immune therapy to prevent or treat obesity, diabetes and inflammation," Sun said.

免疫疗法

分析

对领域进行一次全面的分析。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用