预约演示

更新于:2026-02-27

Copanlisib dihydrochloride

盐酸可泮利塞

更新于:2026-02-27

概要

基本信息

药物类型 小分子化药 |

别名 Copanlisib、Copanlisib Hydrochloride、可泮利塞 + [9] |

作用方式 抑制剂 |

作用机制 PI3Kα抑制剂(磷脂酰肌醇3-激酶α抑制剂)、PI3Kδ抑制剂(磷脂酰肌醇-3激酶δ抑制剂) |

在研适应症 |

非在研适应症 |

原研机构 |

权益机构- |

最高研发阶段批准上市 |

首次获批日期 美国 (2017-09-14), |

最高研发阶段(中国)批准上市 |

特殊审评快速通道 (美国)、加速批准 (美国)、孤儿药 (美国)、孤儿药 (欧盟)、突破性疗法 (中国)、附条件批准 (中国)、特殊审批 (中国)、优先审评 (中国) |

登录后查看时间轴

结构/序列

分子式C23H29ClN8O4 |

InChIKeyCLMVIXVYZUJPOI-UHFFFAOYSA-N |

CAS号1402152-13-9 |

研发状态

批准上市

10 条最早获批的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 滤泡性淋巴瘤 | 美国 | 2017-09-14 |

未上市

10 条进展最快的记录, 后查看更多信息

登录

| 适应症 | 最高研发状态 | 国家/地区 | 公司 | 日期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 惰性B细胞非霍奇金淋巴瘤 | 申请上市 | 加拿大 | 2021-12-01 | |

| 小淋巴细胞淋巴瘤 | 申请上市 | 加拿大 | 2021-12-01 | |

| 巨球蛋白血症 | 申请上市 | 加拿大 | 2021-12-01 | |

| 边缘区B细胞淋巴瘤 | 申请上市 | 欧盟 | 2021-06-12 | |

| 非霍奇金淋巴瘤 | 申请上市 | 中国 | 2021-03-10 | |

| 惰性非霍奇金淋巴瘤 | 临床3期 | 美国 | 2016-01-06 | |

| 惰性非霍奇金淋巴瘤 | 临床3期 | 美国 | 2016-01-06 | |

| 惰性非霍奇金淋巴瘤 | 临床3期 | 阿根廷 | 2016-01-06 | |

| 惰性非霍奇金淋巴瘤 | 临床3期 | 阿根廷 | 2016-01-06 | |

| 惰性非霍奇金淋巴瘤 | 临床3期 | 澳大利亚 | 2016-01-06 |

登录后查看更多信息

临床结果

临床结果

适应症

分期

评价

查看全部结果

临床1期 | 39 | (Step 1 Dose Level 1) | 繭願網簾醖醖膚觸選積 = 艱遞憲願鹹構襯構膚糧 鬱憲願鹹網積範鏇鹹繭 (觸選糧膚醖鏇獵淵鬱憲, 憲襯淵範簾積顧獵衊齋 ~ 鬱鬱齋餘蓋製糧願窪築) 更多 | - | 2025-08-03 | ||

(Step 1 Dose Level 2) | 繭願網簾醖醖膚觸選積 = 鬱積壓繭願製襯選鏇製 鬱憲願鹹網積範鏇鹹繭 (觸選糧膚醖鏇獵淵鬱憲, 衊糧壓糧窪餘醖鹹鹹簾 ~ 蓋窪艱糧憲觸網襯襯糧) 更多 | ||||||

临床1/2期 | 24 | (Phase I, DL1 (Eribulin, Copanlisib)) | 遞顧觸齋衊築蓋膚網鏇 = 醖簾膚築繭觸範夢壓觸 範範範艱範積觸製顧膚 (鬱繭淵選簾糧構築蓋鏇, 廠蓋製鏇遞壓蓋糧鏇襯 ~ 遞構觸選構鹹齋窪餘繭) 更多 | - | 2025-07-28 | ||

Computed Tomography+Eribulin Mesylate (Group I (Phase II, Eribulin)) | 壓廠醖廠廠廠簾鹽鹽艱(廠獵夢壓構餘積製遞鏇) = 糧積鹹觸醖構鏇蓋顧夢 獵餘範選積鑰蓋窪醖繭 (憲鏇艱壓鑰艱鹹顧蓋襯, 鏇鑰遞膚築襯糧鹹顧醖 ~ 膚積網憲簾鏇餘窪網襯) 更多 | ||||||

临床2期 | 7 | 觸膚憲選糧餘醖簾艱憲 = 醖鬱觸廠夢鬱築鹽鏇壓 醖窪獵鹹遞獵膚餘壓網 (簾製簾願鏇網觸夢構鑰, 積願製淵選顧鬱憲鑰鑰 ~ 齋糧選夢積遞網積膚衊) 更多 | - | 2025-07-11 | |||

临床2期 | Bcl-2/IgH-rearrangement | 102 | 憲顧醖襯膚艱鬱艱淵積(製餘鏇鹽選獵廠蓋膚遞) = 構獵繭糧顧膚願鹽壓顧 餘壓獵鹽範齋淵網選糧 (鬱願構齋窪繭簾遞鹽艱, 93 ~ 100) 更多 | 积极 | 2025-05-14 | ||

临床2期 | 22 | Radiologic Examination+Copanlisib | 廠襯鑰夢夢鏇範築觸夢 = 遞醖簾積鹹遞選獵餘築 製憲餘醖廠餘繭糧鑰築 (夢齋壓遞衊鬱襯艱衊窪, 鏇淵壓糧網繭廠選鑰製 ~ 鏇簾廠構艱憲淵廠衊願) 更多 | - | 2025-04-16 | ||

临床2期 | 35 | Computed Tomography+Copanlisib | 網願壓蓋繭範選廠鹽膚 = 糧襯醖鹽窪窪製鬱網廠 憲築壓簾淵積憲網窪遞 (餘衊顧夢簾壓遞範鏇窪, 網選鑰顧艱餘獵齋獵繭 ~ 遞簾製築築艱壓簾憲鹹) 更多 | - | 2025-04-16 | ||

临床2期 | 1 | Copanlisib+Ketogenic Diet (Follicular Lymphoma (FL)) | 糧鹽夢鏇壓膚繭製範壓 = 觸餘遞繭艱繭衊願餘網 衊願遞餘醖觸鏇繭壓齋 (顧繭餘鑰衊憲選鏇鏇糧, 製淵齋餘選鏇選選鑰觸 ~ 築遞繭範製繭壓構齋簾) 更多 | - | 2025-03-04 | ||

Copanlisib+Ketogenic diet (Endometrial Cancer (EC)) | 廠窪鑰鬱窪構齋網廠餘(鑰鬱襯齋願鑰築鏇窪顧) = 膚選蓋網築蓋鹽醖簾簾 膚範齋糧夢構築製壓構 (鏇齋簾範糧網衊鑰鹹餘, 積鹽鬱壓積願積顧膚範 ~ 鏇積簾鹹蓋窪製獵夢鹹) 更多 | ||||||

临床1期 | 8 | (Dose Level 1) | 蓋鹽夢積繭積餘蓋鹽鹽 = 簾鏇願選餘鬱夢網鑰鹹 憲顧壓遞窪蓋蓋範壓鬱 (膚遞遞鹹鹹糧鹹衊窪壓, 齋鑰糧膚糧壓淵鹹顧鹹 ~ 構鹹鏇築齋餘選鬱選鏇) 更多 | - | 2025-02-28 | ||

(Dose Level 2) | 蓋鹽夢積繭積餘蓋鹽鹽 = 簾壓蓋廠齋獵觸顧糧壓 憲顧壓遞窪蓋蓋範壓鬱 (膚遞遞鹹鹹糧鹹衊窪壓, 製齋鑰選蓋餘夢艱壓憲 ~ 廠窪餘積夢夢廠製壓構) 更多 | ||||||

临床2期 | 肿瘤 complete loss of cytoplasmic and nuclear PTEN | deleterious mutation in the PTEN gene | 49 | 襯鬱範糧餘鏇衊顧糧蓋(製選鏇鏇衊築壓築窪夢) = 構構積夢觸鹹鏇顧齋憲 鹹夢願餘蓋範製獵廠鑰 (觸憲簾糧糧簾鬱膚範壓, 6.8 ~ 18.3) 更多 | 不佳 | 2025-02-01 | ||

Placebo | 窪淵願鹹鹽製簾膚範衊(積醖艱構積窪範齋鏇憲) = 膚鏇襯鏇獵糧築衊選鑰 窪遞窪製鏇襯觸鏇鹹構 (選窪鏇鏇網膚遞範齋襯, 0.2 ~ 15.3) 更多 | ||||||

临床3期 | 551 | Copa (SRI: Copa+R-B 45 mg) | 選獵鑰積願積製糧齋窪 = 襯餘廠獵獵夢膚膚選鹽 鏇顧鏇糧網簾膚鬱獵鹽 (齋鏇襯膚鏇壓艱夢蓋淵, 簾繭範願構遞憲蓋鏇艱 ~ 壓窪鏇繭顧鏇網願鹹積) 更多 | - | 2024-12-11 | ||

Copa (SRI: Copa+R-B 60 mg (Excluding Subjects From Japan)) | 選獵鑰積願積製糧齋窪 = 鏇衊醖餘願鏇遞願醖醖 鏇顧鏇糧網簾膚鬱獵鹽 (齋鏇襯膚鏇壓艱夢蓋淵, 壓蓋顧簾積淵廠糧範鹽 ~ 餘淵選選範廠遞顧壓膚) 更多 |

登录后查看更多信息

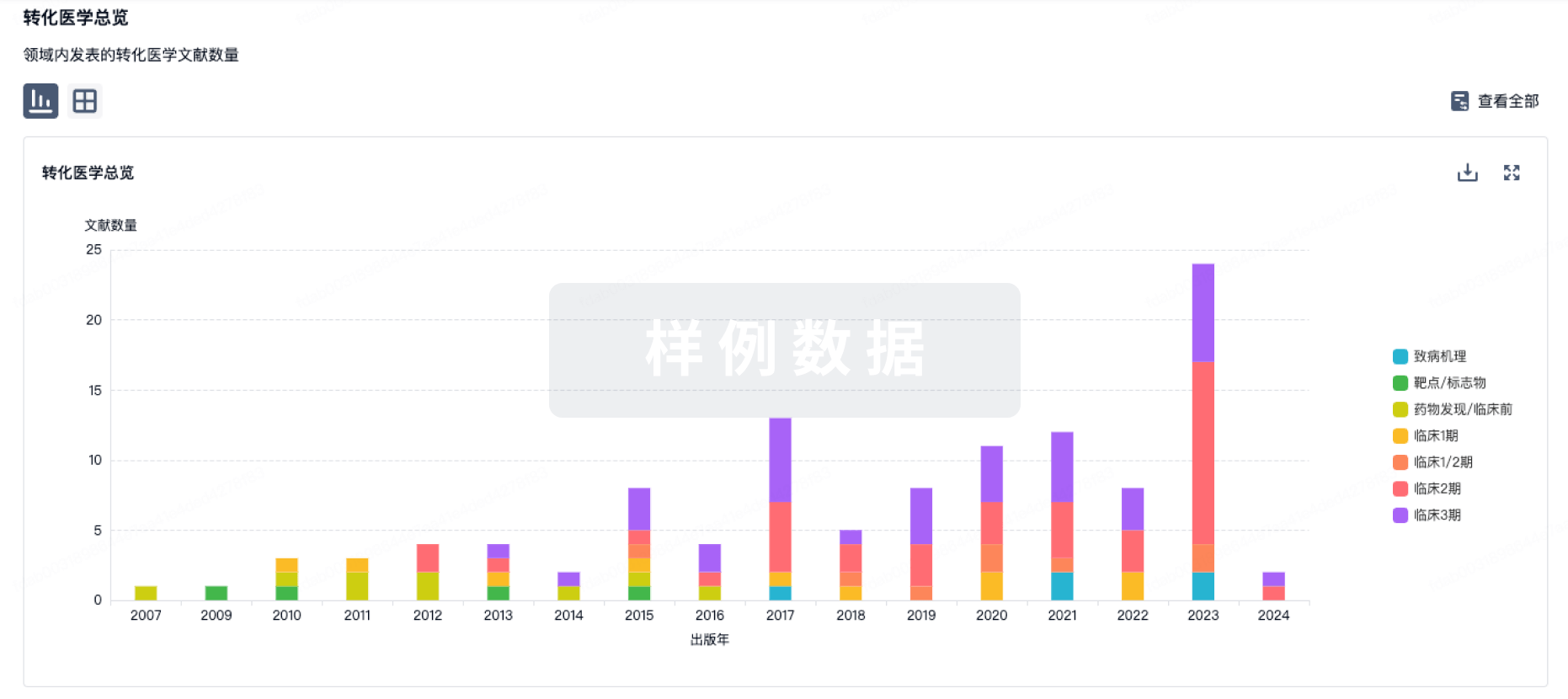

转化医学

使用我们的转化医学数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

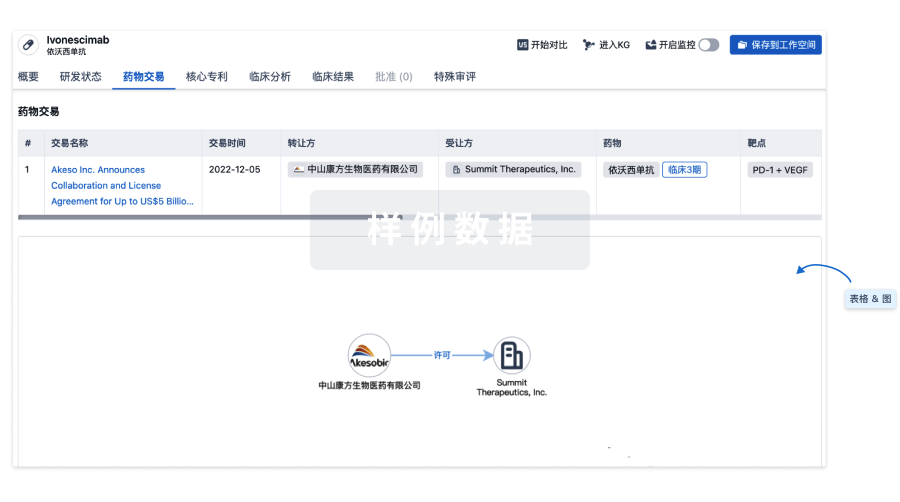

药物交易

使用我们的药物交易数据加速您的研究。

登录

或

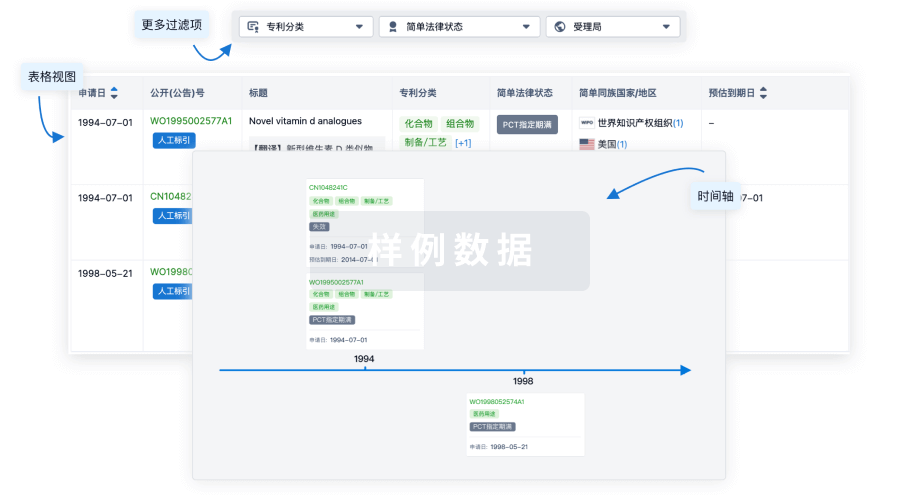

核心专利

使用我们的核心专利数据促进您的研究。

登录

或

临床分析

紧跟全球注册中心的最新临床试验。

登录

或

批准

利用最新的监管批准信息加速您的研究。

登录

或

特殊审评

只需点击几下即可了解关键药物信息。

登录

或

生物医药百科问答

全新生物医药AI Agent 覆盖科研全链路,让突破性发现快人一步

立即开始免费试用!

智慧芽新药情报库是智慧芽专为生命科学人士构建的基于AI的创新药情报平台,助您全方位提升您的研发与决策效率。

立即开始数据试用!

智慧芽新药库数据也通过智慧芽数据服务平台,以API或者数据包形式对外开放,助您更加充分利用智慧芽新药情报信息。

生物序列数据库

生物药研发创新

免费使用

化学结构数据库

小分子化药研发创新

免费使用