点击上方关注

点击下方点赞

随着肿瘤生物学与免疫学研究的持续深化,2025年肿瘤创新疗法领域正经历着一场多维度的进化与革新。从结构日益复杂的抗体药物偶联物(ADC)到功能强大的双特异性抗体,再到挑战更高技术壁垒的三特异性抗体(多抗)及T细胞衔接器(TCE),各类创新药物不仅在结构及作用机制设计上实现了里程碑式的突破,更在临床研究中屡获佳绩,展现出破解耐药难题、提升疗效的巨大潜力。此外,以CAR-T为代表的细胞疗法也在不断突破技术瓶颈,拓展应用边界。本文将梳理2025年度上述五大类创新药物在关键临床试验中的核心数据与循证医学证据,旨在复盘本年度肿瘤创新治疗领域的突破性进展,并展望其未来格局。

一

ADC药物:精准打击与耐药突围

在ADC药物领域,针对EGFR、HER3、TROP2及HER2等靶点的创新研发正在重塑实体瘤的治疗格局,特别是双抗ADC、双载荷的出现,为克服耐药提供了新思路。

1

EGFR×HER3双抗ADC

百利天恒Iza-bren,全球首创,开启ADC治疗新纪元

EGFR和HER3在多种肿瘤细胞表面高表达,两者之间存在信号通路的相互作用,共同参与肿瘤细胞的增殖、迁移和血管生成等过程。与单一靶点ADC 药物相比,双特异性抗体偶联药物能够通过多结合发挥肿瘤抑制作用,有望克服耐药性问题。

Iza-bren(BL-B01D1)是由百利天恒自主研发的全球首创且唯一进入III期临床阶段的EGFR×HER3 双抗ADC。截至目前,iza-bren已在中美进行40 余项临床试验,其中已有2 项适应症被CDE 纳入优先审评品种名单,分别为:复发性或转移性鼻咽癌、复发性或转移性食管鳞癌,并且近期该两项适应症上市申请获受理。

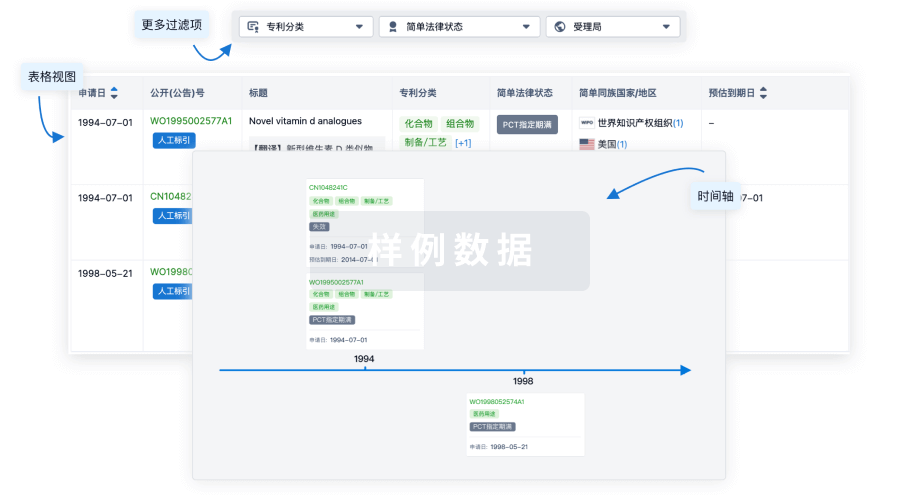

图:iza-bren上市申请,获国家药品监督管理局药品审评中心(CDE)受理

2025 WCLC中,百利天恒报道了iza-bren在肺癌领域最新研究进展,在一项Ⅱ期临床研究中,40 例受试者接受iza-bren +奥希替尼一线治疗,研究结果显示:ORR为100%,12个月PFS率为92.1%,12个月OS率为94.8%;另一项Ⅰ/Ⅱ期研究纳入既往接受过EGFR-TKI 但未接受过化疗的50例受试者,研究结果显示,总人群 mPFS 长达 12.5 个月,ORR 达 66.0%,DCR 高达 90.0%,mDoR 长达 13.7 个月。iza-bren展现出了具有前景的疗效和可控的安全性, 有望克服第三代 EGFR-TKI 治疗后的耐药难题,为 EGFR突变NSCLC患者提供新的治疗策略。

君实生物JS212,中美双报加速全球进程

JS212是由君实生物开发的EGFR×HER3 双抗ADC,主要用于晚期恶性实体瘤的治疗。2025年1月,JS212申请的临床试验获得国家药监局受理,并于2025年3月获得国家药监局批准。并且近日君实生物收到FDA的通知,JS212用于治疗晚期实体瘤的临床试验申请获得FDA批准。

2

HER2双表位ADC

中国生物制药TQB2102,平衡疗效与安全性,重塑治疗格局

除了双抗ADC,针对HER2不同表位的创新设计同样亮眼。TQB2102是正大天晴自主研发的一种靶向HER2两个非重叠表位ECD2及ECD4的ADC。

2025 ASCO年会,其公布的I期临床研究显示:共纳入181例经治无标准治疗方案的晚期实体瘤患者,包括HER2阳性和HER2低表达。有效性显示:6mg/kg及以上剂量组中,HER2阳性乳腺癌ORR为51.3%,HER2低表达乳腺癌ORR为51.5%,HER2高表达(HER2 3+)结直肠癌ORR为34.8%,HER2阳性胃或胃食管结合部腺癌ORR为70%。31%的乳腺癌受试者在T - DM1/DS - 8201耐药后使用TQB2102治疗仍有效。安全性显示:仅出现1例(0.55%) 2级间质性肺病(ILD),发生率远低于同类药物DS - 8201(发生率>10%)。

图:2025年ASCO年会,TQB2102摘要

2025年11月25日,TQB2102单药用于HER2阳性乳腺癌新辅助治疗的Ⅱ期临床研究在线发表于Journal of Clinical Oncology。研究共4个队列,每个队列26例受试者,结果显示:8周期队列(队列2和队列4)合并分析的tpCR率为73.1%,6mg/kg 8周期队列(队列2)的tpCR率高达76.9%,4个队列全部满足“疗效优于历史对照”的判断条件。安全性方面,总体3级治疗相关不良事件发生率为27.9%,无治疗相关死亡报告,临床所关注的ILD较轻,且经治疗后可恢复。

图:TQB2102Ⅱ期临床研究各队列tpCR率

目前,全球尚无双抗ADC药物获批上市。TQB2102在多个晚期恶性肿瘤中展现出显著的临床获益,且ILD发生率低,实现了疗效和安全性的有效平衡。目前,TQB2102正在开展III期临床试验,有望重塑HER2 ADC治疗格局。

3

EGFR/c-Met双抗ADC

中国生物制药TQB6411,跻身全球研发第一梯队

TQB6411是中国生物制药自主开发的一款靶向EGFR/c-Met的双抗ADC药物。TQB6411于2025年6月13日获得NMPA批准,拟用于治疗晚期恶性肿瘤。目前研发进度处于全球第一梯队,全球同类药物均处于I期阶段。

图:CDE官网TQB6411临床试验公示信息

4

TROP2双载荷ADC

康弘生物KH815,双效协同机制,领跑全球双载荷ADC研发

KH815是康弘生物自主研发的一种具有抗耐药潜力的靶向TROP2的新型双载荷(dual-payload) ADC。KKH815的双载荷分别为:拓扑异构酶I抑制剂(TOP1i)和RNA聚合酶II抑制剂(RNA POL IIi)。能够同时抑制RNA合成和诱导DNA双链断裂,具有双效协同机制。

2025 AACR年会中,临床前研究结果显示:在细胞来源异种移植(CDX)和人源肿瘤异种移植(PDX)模型中,KH815均呈现剂量依赖性肿瘤生长抑制,且在同等甚至更低剂量下均优于单TOP1i ADC。2025年4月16日:全球首款双载荷ADC(KH815)成功获得国家药品监督管理局签发的临床试验批准。

图:2025年AACR年会,KH815摘要

5

CEACAM5双载荷ADC

信达生物IBI3020 ,全球首创,双重杀伤机制,完成首例临床给药

IBI3020是信达生物自研的DuetTx双载荷ADC。抗体靶向癌胚抗原相关细胞粘附分子5(CEACAM5),并创新性地采用双载荷设计,实现肿瘤细胞杀伤的双重机制。2025年4月30日信达生物宣布其全球首创CEACAM5 双载荷ADC(IBI3020)完成临床I期研究首例受试者给药。

图:IBI3020完成临床I期研究首例受试者给药

二

双抗药物:免疫微环境的深度调控

如果说ADC药物侧重于“精准打击”,那么双抗药物则致力于“免疫激活”。2025年,双抗研发重点已从简单的双靶点阻断转向对肿瘤免疫微环境(TME)的深度调控与功能性重塑。通过引入IL-2、TIGIT、VEGF等关键通路,研发人员试图解决单药疗效瓶颈及耐药问题,挖掘免疫治疗的深层潜力。

1

PD-1/IL-2双抗

君实生物JS213,优先激活肿瘤浸润T细胞

JS213是由君实生物开发的PD-1/IL-2 双功能性抗体融合蛋白,临床前结果表明:JS213 优先刺激肿瘤浸润 CD8+T 细胞的扩增,对外周血中 T 细胞和自然杀伤(NK)细胞影响较小,在抗 PD-1 单抗敏感或耐药的小鼠肿瘤模型中均显示出良好的疗效和安全性。

在2025年第40届SITC年会上,君实生物公布了JS213用于晚期肿瘤患者的首次人体I期研究的安全性和有效性临床研究,研究结果显示:25例患者接受了0.3、0.6和1 mg/kg剂量的JS213治疗,其中20例疗效可评估患者中,ORR为35%,DCR为75%。安全性方面,大多数治疗相关不良事件(TRAE)为低级别,最常见的TRAE包括关节痛(50%)、疲劳(35%)、皮疹(35%)、恶心(31%)和甲状腺功能减退症(23%)。对于晚期肿瘤患者,包括对抗PD-(L)1原发性和继发性耐药、以及通常对免疫单药治疗无反应的pMMR型肿瘤患者,JS213表现出良好的抗肿瘤活性及可控的安全性。目前该研究剂量递增试验仍在进行中,以确定其MTD/RP2D。

图:2025年SITC年会,JS213摘要

信达生物IBI363,设计优化,实现降毒增效

IBI363是由信达生物自主研发的全球首创PD-1/IL-2α-bias双特异性融合蛋白,其IL-2臂经过了设计改造,保留了其对IL-2 Rα的亲和力,但削弱了对IL-2Rβ和IL-2Rγ的结合能力,以此降低毒性;而PD-1结合臂可以同时实现对PD-1的阻断和IL-2的选择性递送。

2025 ASCO年会,信达生物分别公布了IBI363在晚期结直肠癌、免疫经治的黑色素瘤、晚期非小细胞肺癌的临床研究数据。其中IBI363单药或联合贝伐珠单抗治疗晚期结直肠癌患者的疗效及安全性研究中,分别纳入了接受IBI363单药治疗的68例和IBI363+贝伐珠单抗治疗的73例患者。在可评估疗效的患者中(单药n=63,联合n=68),ORR分别为12.7%和23.5%。单药组中位缓解持续时间为7.5个月,联合组数据尚未成熟。单药组mOS为16.1个月,联合组数据尚未成熟。特别是在无肝转移且接受联合治疗的患者中(n=31),ORR为38.7%, DCR为83.9%,PFS为9.6个月。已有的临床数据提示IBI363联合贝伐在结直肠癌人群具有良好的安全性和有效性,值得进一步探索。IBI363在非小细胞肺癌、黑色素瘤德临床数据中,同样显示出良好的抗肿瘤作用,未来可能为该类患者提供更理想的治疗选择。

图:2025年ASCO年会,IBI363摘要

2

PD-1/TIGIT双抗

泽璟生物ZG005,协同增效,激活免疫杀伤

ZG005是苏州泽璟生物开发的重组人源化抗PD-1/TIGIT双特异性抗体,根据公开查询,ZG005是全球率先进入临床研究的同靶点药物之一,目前全球范围内尚未有同类机制药物获批上市。

2025 ESMO年会,泽璟生物公布了ZG005联合依托泊苷及顺铂(EP)在一线晚期神经内分泌癌患者中的安全性、药代动力学特征及初步疗效的I/II期临床研究(ZG005-004),有效性显示:31例受试者中,ORR:接受 ZG005 10 mg/kg + EP治疗为 50.0%,ZG005 20 mg/kg + EP为 61.1%,安慰剂+EP为28.6%。各组、DCR分别为83.3%、100%和100%,中位PFS和DoR数据尚未成熟。安全性显示:在ZG005+EP的两组中,最常见(≥20%)的 TRAE 依次为中性粒细胞计数降低、白细胞计数降低、贫血、血小板计数降低、乏力,且发生率绝大多数均较对照组更低。在晚期神经内分泌癌的患者中,ZG005 联合化疗安全性耐受性良好,显示了良好的疗效,支持其开展进一步的临床研究。

图:2025 ESMO年会 ZG005摘要

3

PD-1/VEGF双抗

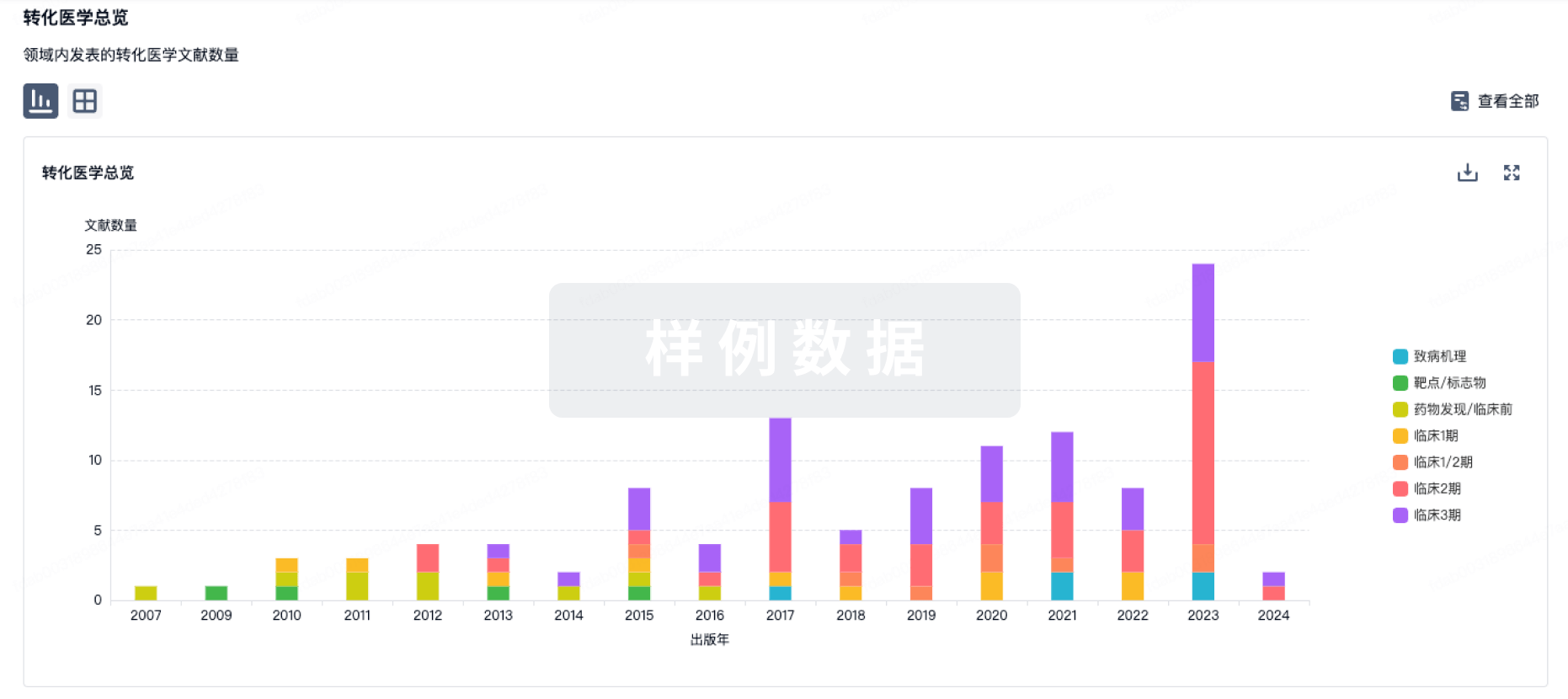

康方生物AK112,登顶《柳叶刀》,确立一线治疗新标准

依沃西是康方生物自主研发的、全球首创PD-1/VEGF双特异性肿瘤免疫治疗药物。2025 ESMO主席论坛及《柳叶刀》(THE LANCET)主刊同步发表HARMONi - 6 /AK112 – 306:一项评估依沃西联合化疗对比替雷利珠联合化疗一线治疗晚期sq-NSCLC的随机、对照、多中心III期临床试验研究。研究结果显示:依沃西+化疗与替雷利珠+化疗的组间PFS HR = 0.60,P < 0.0001;依沃西组mPFS长达11.1个月,对照组mPFS为6.9个月,该研究取得了组间PFS绝对值改善△PFS = 4.24个月。在各个亚组中,依沃西联合化疗较替雷利珠联合化疗显著获益,包括无论PD - L1表达水平(PD - L1阳性或阴性)、无论是否伴肝转移、无论基线转移部位数量的人群。依沃西组总体安全性良好,未发现新的安全性信号。与治疗相关的严重不良事件发生率、三级及以上出血事件发生率与对照组相似。依沃西联合化疗一线治疗sq-NSCLC的新适应症上市申请(sNDA)目前已获CDE受理并在审评中,有望为更多患者带来希望。

图:依沃西+化疗与替雷利珠+化疗的组间PFS

华奥泰HB0025,挺进III期临床挑战肺鳞癌

HB0025 是由华奥泰自主研发的一款创新型抗 PD-L1/VEGF 双特异性融合蛋白。2025 ESMO 会议,华奥泰公布了HB0025+化疗一线治疗晚期肺鳞癌和肺腺癌II期临床研究,研究显示具有较好的ORR和DCR,尤其在PD-L1阴性人群中ORR的响应率高,3级以上irAEs发生率低。同时,HB0025 多个II 期临床试验正在评估中,涵盖包括子宫内膜癌、结直肠癌、三阴乳腺癌等多种实体瘤。2026年1月6日,CDE显示,华海药业启动了HB0025首个III期临床研究:评估HB0025联合化疗对比帕博利珠单抗联合化疗一线治疗局部晚期或转移性鳞状非小细胞肺癌有效性的随机对照、双盲、多中心III期临床研究(DUALIGHT-02)。

图:2025 ESMO年会 HB0025摘要

其它PD-1/VEGF 双抗),如:BMS的 PM8002(PD-L1/VEGF双抗)、辉瑞(三生制药)的SSGJ-707(PD-1/VEGF双抗)、神州细胞的 SCTB14(PD-1/VEGF双抗)均已进入临床III期。

三

多抗:下一代疗法的前沿探索

在双抗药物蓬勃发展之际,多抗作为下一代治疗药物的代表,正在快速崛起。如三特异性抗体这类药物通过同时衔接三个靶点,实现了更复杂的免疫调控机制,尤其在难治性肿瘤和小细胞肺癌等领域展现出突破性的潜力。

1

PD-1/VEGFA/CTLA-4三抗

基石药业CS2009,协同改善肿瘤微环境

CS2009是基石药业自主研发的一款靶向PD-1、VEGFA和CTLA-4的新型三特异性抗体,通过协同作用实现多维度的抗肿瘤效应。其通过阻断PD-1可逆转T细胞耗竭,阻断CTLA-4可促进T细胞活化和增殖,而阻断VEGFA则可抑制肿瘤血管生成,从而改善肿瘤微环境(TME)。在TME中,PD-1和CTLA-4的双重阻断作用通过与VEGFA的交联显著增强,同时,CS2009可优先结合PD-1和CTLA-4双阳性的肿瘤浸润T细胞,并最大程度上弱化对外周T细胞中CTLA-4调节通路的干扰。

2025 ESMO年会,基石药业公布了CS2009的I期临床研究初步数据。CS2009在多种瘤种中展现出令人鼓舞的抗肿瘤活性。截至壁报数据截止日,整体随访时间尚短,尤其高剂量组大部分患者尚未达到方案预设的基线后肿瘤评估时间点:ORR:12.2%,DCR:71.4%。在暂定的RP2D及更高剂量下能观察到更高的ORR(25.0%)。基于I期研究,CS2009的Ⅱ期临床试验采用多队列平行扩展设计,共涵盖15个单药/联合用药队列,覆盖NSCLC、HCC等9个实体瘤适应症。目前,Ⅱ期临床试验正在澳大利亚积极入组。中国IND的获批将会进一步加快临床开发进度,探索与验证CS2009的广阔治疗潜力。

图:2025 ESMO年会 CS2009摘要

2

PD-1/TIGIT/IL-15三抗

汇宇制药HY07121,有望逆转免疫治疗耐药

HY07121是汇宇制药自主研发的注射用HY07121是靶向PD-1/TIGIT/IL-15 的三靶点抗体。体外药效学研究表明,HY07121通过特殊设计获得的多抗分子在等摩尔数情况下,刺激人免疫细胞因子IFN-γ分泌水平比三个靶点联合用药表现出更优的潜力;体内药效学研究结果显示,HY07121对 PD-1抗体耐药的肿瘤模型仍然良好的药效;能够诱导stem-like T细胞及 NKT细胞相关基因的表达上调,促进CD8+T细胞及NK细胞在瘤内的扩增和浸润。HY07121一方面可以补充免疫细胞来源,增加瘤内效应细胞的数量;另一方面可以从多角度将因持续战斗而耗竭的免疫细胞恢复功能,从而不但加强了免疫疗效,并且克服部分免疫治疗患者获得性耐药问题。其临床I期研究目前正在持续推进。

四

TCE疗法:以“免疫细胞重定向”实现肿瘤精准杀伤

T细胞衔接器(T cell engagers,TCE)作为新兴癌症免疫抗体疗法,通过在空间上拉近 T 细胞与靶细胞的距离,触发 T 细胞激活,实现精准杀伤,在血液瘤和部分实体瘤中展现出强大潜力。2025年,TCE领域在靶点选择、和临床数据上均取得了显著进展,成为肿瘤免疫治疗中备受瞩目的新兴力量。

1

DLL3×DLL3×CD3三特异性TCE

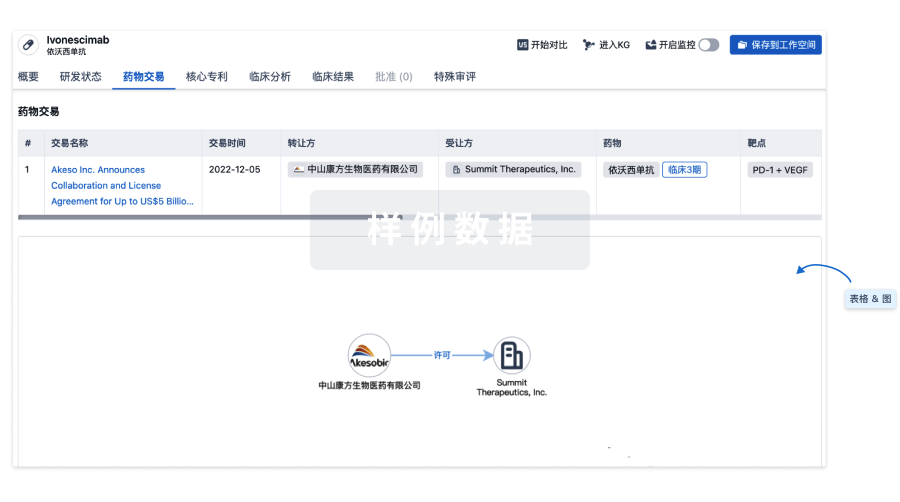

泽璟制药ZG006,全球首创,成功授权艾伯维

ZG006是苏州泽璟生物自主开发的First-in-Class型三特异性TCE,是一种针对两个不同DLL3表位及CD3 的三特异性T细胞衔接器。ZG006的抗DLL3端与肿瘤细胞表面不同DLL3表位相结合,抗CD3端结合T细胞。ZG006衔接肿瘤细胞和T细胞,将T细胞拉近肿瘤细胞,从而利用T细胞特异性杀伤肿瘤细胞。

2025 ESMO Asia学术年会, 泽璟生物公布了ZG006单药治疗难治性晚期小细胞肺癌患者中的II期剂量优化临床研究(ZG006-002),有效性显示:10mg Q2W组(30例)和30mg Q2W组(30例)ORR分别为60.0%和66.7%,DCR两组均为73.3%;mPFS分别为7.03月和5.59月;mOS两组均未成熟,12个月的OS率分别为69.1%和58.2%。安全性显示:两组的整体耐受性和安全性均良好,未发生任何因治疗期不良事件(TEAE)导致的永久停药。

2025 ESMO学术年会,泽璟生物公布了ZG006在晚期神经内分泌癌患者中的Ⅱ期剂量扩展临床研究(ZG006-003),有效性显示:10mg Q2W和30mg Q2W组的确认ORR分别为 22.7%和 40.9%,DCR分别为45.5%和72.7%,mPFS、mDoR均尚未成熟。安全性显示,两组的安全性及耐受性总体均良好,19人报告了3级/4级TRAEs(35.2%),没有五级TRAE。

图:2025 ESMO年会 ZG006摘要

2025年9月23日,泽璟制药在CDE登记了一项关于注射用ZG006对比研究者选择的化疗在复发性小细胞肺癌患者中的有效性和安全性的多中心、随机对照、开放标签的III期临床研究。ZG006成为全球首个启动三期临床的三抗药物。

2025年12月31日,泽璟制药宣布将DLL3/DLL3/CD3三特异性TCE ZG006的大中华区外全球权益授权给艾伯维。

2

GPRC5D/BCMA/CD3三特异性TCE

齐鲁制药QLS4131,有望改写多发性骨髓瘤治疗格局

QLS4131是齐鲁制药自主研发的(GPRC5D/BCMA/CD3)三特异性TCE,可以特异性结合T细胞表面CD3与肿瘤细胞表面的BCMA和GPRC5D,从而将T细胞招募到肿瘤部位,促进效应T细胞存活与增殖,并通过释放颗粒酶和穿孔素等杀伤肿瘤细胞。

2025年ASH中,齐鲁制药公布了QLS4131治疗复发/难治性多发性骨髓瘤(RRMM)的I期临床研究数据,在15名接受QLS4131注射治疗且疗效可评估的患者中,总体客观缓解率为60%(≥VGPR 40%),在30 µg/kg 队列中,100%的患者达到VGPR及以上的缓解。在10 µg/kg IV剂量组中的2名既往BCMA靶向CAR-T/CAR-NK治疗失败的患者中:1 例达到严格完全缓解(sCR),1 例达到部分缓解(PR)。QLS4131在RRMM中的初步剂量递增数据表明,其毒性可耐受,未观察到DLT,且与已发表的竞争对手的数据相比,相关不良事件的发生率相对较低。

图:2025 ESMO年会 ZG005摘要

五

CAR-T疗法:从体外定制到体内“即用即造”

嵌合抗原受体T细胞(CAR-T)疗法作为癌症治疗的革命性突破,已成功将患者的T细胞在体外进行基因改造,使其能够精准识别并杀伤肿瘤。然而,这种体外制备模式面临着成本高昂、生产周期长、难以标准化等挑战,限制了其更广泛的应用。为了突破这些瓶颈,In vivo CAR-T(体内生成CAR-T)技术应运而生。其核心思想是“就地制造”:通过将编码CAR的基因,利用病毒载体(如AAV)等工具,直接递送至患者体内。这些载体在体内感染患者的T细胞,将其“就地”转化为能够特异性识别并杀伤肿瘤细胞的CAR-T细胞。这一技术带来了三大显著优势:成本大幅降低,省去了体外生产环节;制备时间极短,可快速响应临床需求;易于标准化生产,有望实现“现货型”细胞疗法。2025年,In vivo CAR-T疗法在临床应用方面也取得了重要进展。

1

CD19 In Vivo CAR-T

微滔生物GT801,精准靶向无脱靶,展现NHL治疗新潜力

GT801是微滔生物自主研发的In Vivo CAR-T产品,其是一款通过T细胞靶向LNP递送优选mRNA的创新型anti-CD19 in vivo CAR产品。

2025 ASH年会,微滔生物以口头报告形式公布了其最新研究进展,至2025年11月底,针对2例未接受淋巴细胞清除预处理的非霍奇金淋巴瘤(NHL)患者,分别实施了3次(0.5 mg/次)及4次(1.5 mg/次)的给药治疗。临床观察表明,患者整体耐受度较好,外周血T细胞的CAR表达丰度高,并在各次给药后呈现出稳定、持久的有效扩增特征。值得注意的是,外周血单核细胞中未见CAR表达,这充分说明GT801无脱靶隐患,且T-LNP平台能精准提升靶向性并防止非特异性摄取。完成多次给药的第4周,两名患者均评估为部分缓解。

图:2025 ASH年会GT801摘要

易慕峰 IMV101:靶向CD19,单次给药长效抑瘤

IMV101是易慕峰生物自主研发的In Vivo CAR-T产品,其为靶向CD19的新型体内CAR-T疗法,基于慢病毒载体设计,载体表面覆盖突变型MXV糖蛋白,消除受体结合能力但保留膜融合活性,同时整合T细胞靶向模块TCM3,可高特异性识别并结合T细胞表面受体,实现高效感染。通过单次静脉注射,能在体内直接将CAR基因递送至T细胞,使其原位转化为具有肿瘤杀伤功能的CD19 CAR-T细胞。

2025ASH年会,易慕峰公布了IMV101的临床前研究,研究显示:基于人源化免疫系统小鼠肿瘤模型,单次给予IMV101后,肿瘤生长受到显著抑制。与此同时,外周血中存在持续生成的功能性CAR-T细胞并进行扩增,这一结果完全契合了“单次给药、长效持久”的预期药效特征。

图:2025 ASH年会IMV101摘要

综上所述,2025年的肿瘤创新疗法领域呈现出百花齐放的态势。无论是双抗ADC药物在克服耐药上的精准突破,双特异性抗体在免疫微环境调控上的深度探索,三特异性抗体在结构设计与疗效上的潜力爆发,TCE疗法在细胞重定向上的精准杀伤,还是CAR-T疗法在细胞工程上的持续革新,都为未来临床研究提供了丰富的武器库,为患者生存获益带来新的希望。随着更多III期临床结果的公布和产品的获批上市,我们有理由相信,这些创新疗法将逐步改写肿瘤治疗的临床实践,为更多患者带来治愈或长期生存的可能。

1. 四川百利天恒药业股份有限公司公告

2. 中国生物制药有限公司公告

3. 上海君实生物医药科技股份有限公司公告

4. 信达生物制药有限公司公告

5. 中山康方生物医药有限公司公告

6. 浙江华海药业股份有限公司公告

7. 苏州泽璟生物制药股份有限公司公告

8. 基石药业公告

9. 四川汇宇制药股份有限公司公告

10. 齐鲁制药官网

11. 微滔生物官网

12. 易慕峰生物官网

13. 康弘生物

14. 2025 WCLC

15. 2025 ESMO

16. 2025 ASCO

17. 2025 ASH

18. 2025 SITC

19.2025 AACR

天津医科大学第二医院 王海涛

天津医科大学第二医院肿瘤科主任、放疗科主任、精准医学研究中心主任

医学博士,博士生导师,主任医师

天津市性激素与疾病精准医学重点实验室主任

天津市精准医疗学会理事长

天津医科大学“临床人才培养123攀登计划”学科领军人才

美国临床肿瘤学会(ASCO)国际会员

中国临床肿瘤学会(CSCO)理事,天津市抗癌协会常务理事

中国临床肿瘤学会(CSCO)前列腺癌专委会常务委员

中国临床肿瘤学会(CSCO)免疫治疗、血管靶向治疗、泌尿上皮癌、肾癌专委会委员

中国人体健康科技促进会肿瘤个体化精准医疗专委会主任委员

第一/通讯作者在JCO等杂志发表论文

研究入选2022年美国临床肿瘤学会(ASCO)口头报告

中国抗癌协会肿瘤标志专委会肿瘤多学科诊断协作组(MDD)副组长

国家博鳌医疗先行区疑难肿瘤精准治疗真实世界研究协作组组长

中国抗癌协会肿瘤精准治疗专委会委员

中国民族医药学会精准医学分会副会长

天津市医师协会临床精准医疗专业委员会副主任委员

天津市医师协会肿瘤多学科诊疗专委会副主任委员

天津市中西医结合学会循证医学专业委员会副主任委员、肿瘤专委会委员

中华医学会天津分会肿瘤学会委员、泌尿学会精准学组组长、肿瘤学组副组长

天津市抗癌协会中西医结合肿瘤专委会常委、泌尿肿瘤及老年肿瘤专委会委员

主要从事肿瘤的个体化多学科综合治疗及精准治疗的应用基础研究

主持国家自然科学基金面上项目2项

获中国医师协会2016年推动中国前行的力量十大医学新锐奖

同济大学附属同济医院 修冰

同济大学附属同济医院血液科主任医师、博士生导师、副教授

中国抗癌协会血液学转化医学委员会第一届青年委员

上海市医学会血液学分会第11-12届青年副主任委员

上海市中西医结合学会第七届血液病专委会常务委员

上海市女医师协会血液学专业委员会委员

上海市医学会心身医学学会第一届委员

上海市医师协会肿瘤精准诊疗专业委员会第一届委员

上海市医学会输血学会青年委员

上海市医学会血液学专科分会淋巴瘤及骨髓瘤学组会员

同济医院血液科淋巴瘤MDT组长

美国mayo clinic访问学者

主持2项国自然及4项省部级课题,参与国家、部级科研课题10余项,获3项成果奖,发表论文20余篇,参加编著论著3部。

福建医科大学附属第一医院 周俊峰

福建医科大学附属第一医院17区胃肠外科副主任医师,在读博士

福建省医学会肠外肠内营养学分会青年委员会委员兼秘书

福建省抗癌协会胃癌专业委员会委员

福建省海峡医药卫生交流协会胃癌外科分会理事

海医会台海医学会青年工作委员会青年委员

推荐阅读

年度盘点 | 2025 膀胱癌诊疗进展年终盘点年度盘点 | 2025胃癌诊疗:精准治疗全周期迭代,新靶点、新药物重塑治疗格局年度盘点 |2025结直肠癌精准治疗全景报告:指南迭代、新药爆发、研究突破,从精准分层到范式革新年度盘点 |2025年骨肉瘤:指南迭代、新药突破与机制创新全景解读

立

迪

生

物

创新型CRO

上海立迪生物技术股份有限公司(以下简称“立迪生物”)是国家高新技术企业,致力于从事肿瘤个体化精准医疗研究、服务及产品开发,为药企提供药理药效的临床前CRO服务,同时协助医生进行临床的个性化精准医疗。公司拥有AAALAC国际认可的SPF级实验动物中心及先进的仪器设备。旗下有三家全资子公司“上海立闻医学检验所有限公司”(以下简称“上海立闻”)、“上海立闻生物科技有限公司”和“西安立迪生物技术有限公司”(以下简称“西安立迪”),其中,西安立迪具有临床医学检验所资质。